In 1940, Disney released a family-friendly cartoon about Geppetto, an impoverished elderly carpenter who in all of his loneliness decides to craft a wooden childlike marionette puppet for himself. One night, when the doll was complete and the old man went to bed for a good night’s sleep, he spotted a star illuminating the night sky. It was not just any star, but the wishing one, and it shone ever so brightly.

Since it was rare for such a star to be seen, he got up, looked right through his window, and made a wish: “Star light, star bright, first star I see tonight. I wish I may, I wish I might have the wish I wish tonight. Figaro, you know what I wish,” he asked his little furry kitten, “I wished my little Pinocchio might be a real boy.” He looked lovingly at his doll and sighed, adding “Wouldn’t it be nice,” to which a tiny little cricket that had made Geppetto’s workshop his home responded, saying, “A very lovely thought, but not at all practical,” after which he sat back and let the story unfold.

The star, which was not a star at all, but a kindly fairy, had heard the man’s longing and chose to make his wish come true. She made Pinocchio a living puppet who now, backed by Jiminy, a tiny cricket assigned to act as his conscience, must prove to be worthy of becoming a real boy. This lovely animated story of a cheerful puppet who wants to be a boy, throughout all his mischievous acts in the following hours and various challenging temptations he faces, is about teaching kids how a real boy should behave.

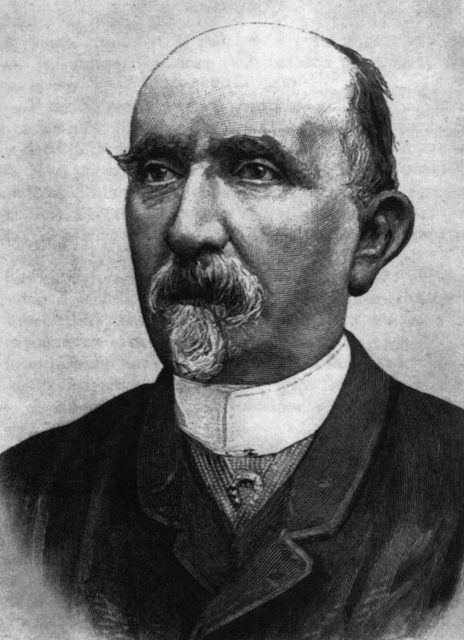

The original book The Adventures of Pinocchio, written by the Italian author Carlo Collodi in the 1880s, had an entirely different tone. Its aim was to show how hard and “not at all practical” it is to be a parent to a mischievous boy.

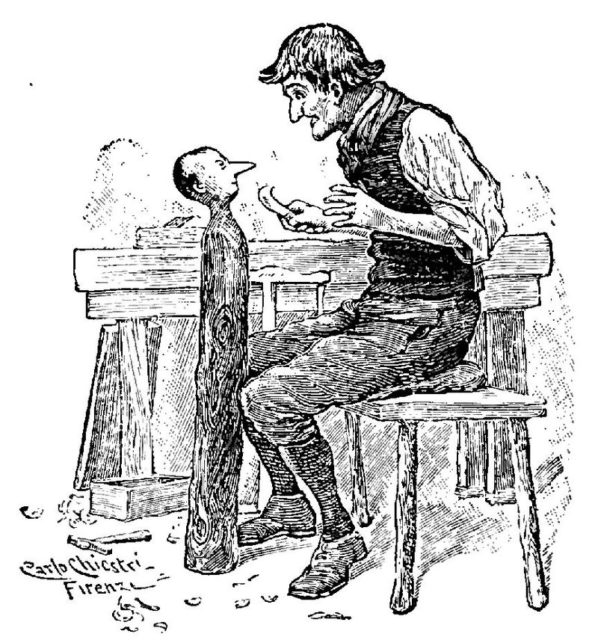

Collodi was never a parent, and his story was anything but lovely. The puppet in the story he wrote and published is penned right from the very beginning as a disobedient rascal and a “wretched boy.” Pinocchio, in the author’s view, is a reflection of the philosophy of how to raise a child that was explored in Emile, or On Education by the 18th century philosopher Jean Jacques Rousseau. In his revolutionary discussion on social education, Rousseau considers allowing a boy to learn the natural consequences of his faulty actions.

“Let them learn nothing from books which they can learn from experience,” he argues. Just the same, this yet-to-be-a-boy puppet, who refused to go to school, was being given the freedom by the author to follow his own senses and desires no matter how disgraceful or wretched they might seem. And what does this “newborn” who was loved so much and so blindly by his creator do? He throws himself into utter defiance and insubordination, he skips classes, creates quarrels between his “father” and their landlord, and runs away from home as soon as he learns to walk. And why? It was because of his drive to disregard the opinions of others (Geppetto) who probably know a thing or two more about life than he.

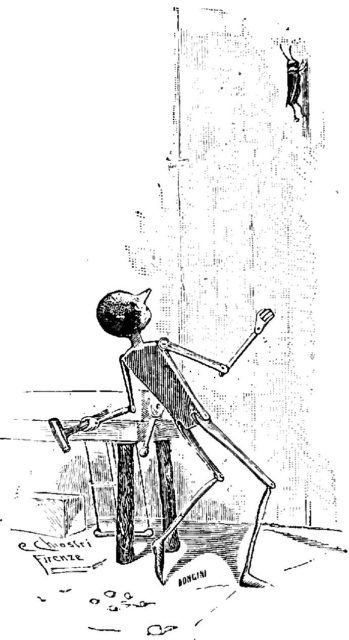

To top it all off, when he’s asked why, he implies that he is abused and his maker is put in prison. While Rousseau argues that a child should learn from nature and explore his own ways, he also asserts that he or she should learn from people as well. So, having first killed his conscience (Jiminy Cricket, the talking cricket in the movie, was squashed on the wall like a fly by Pinocchio) and in total disregard to one man’s opinion on things, a man full of love who longed to father a child and was so happy to be given the chance at last, Pinocchio makes dubious and sometimes even malevolent choices that in the end lead him to be left hanging to die on a tree by people he chose to trust–just out of spite.

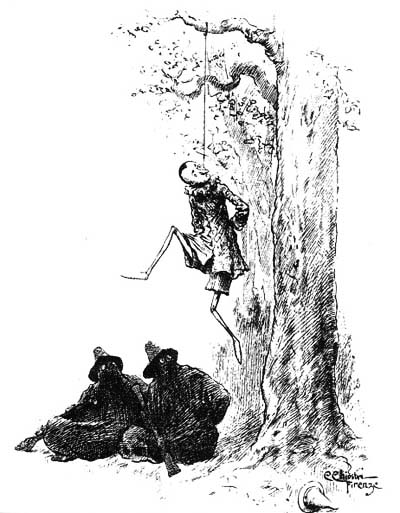

Yes, in the original story Pinocchio is hanged by the Fox and the Cat on a branch of an oak tree. Unsuccessfully, but still. And we as kids considered an amusement park in the middle of a pleasure island turning bad children into to asses was grim. “Right here, boys! Right here! Get your cake, pie, dill pickles, and ice cream! Eat all you can! Be a glutton! Stuff yourselves! It’s all free, boys! It’s all free! Hurry, hurry, hurry, hurry!”

But if only this was the end of it and all he ever endured as a consequence. Throughout the book, Pinocchio feels the repercussion of his actions many times, as he gets mugged, abducted, stabbed on occasion, tied and whipped like a dog, beaten down continuously, and almost starved to death, as well as has his legs burned off one time. Which, despite everything he has ever done, were replaced by Geppetto, the man who “knew nothing” in Pinocchio’s eyes, yet gave him feet to walk once more.

He is by definition one ungrateful brat, there is no denying. And his story is complex, to say the least. And as such, along with the dark manner in which is presented, offered no real interest to a company who wished to give the world a children’s story of a naive boy in a man’s cruel world.

So instead of a lesson for loving parents, a book that aimed to show some practical aspects behind the complex bond that forms between a parent and their child that more often than not will seek to disobey their “maker,” taking every piece of advice and love given for granted, Disney and his crew narrowed it to a sweet, loving children’s story of a naive and ignorant boy, who ought to always listen to what his parent told him.

“Pinocchio is too cocky, too much of a wiseguy, and too puppet-like to be sympathetic to the audience,” was what Walt Disney reportedly said before he put a halt to the making of the cartoon mid-production. In his view, this story of a disrespectful boy who gets tortured and almost killed for his ignorance was not in any way suitable for children.

In order to sell the story, they painted a much nicer picture of a naive helpless boy. The lesson is that those who are brave enough and always truthful will find salvation. Which, truth be told, is a story much easier to sell.