When someone mentions Godzilla and its Japanese origins, people often think of outdated visual effects, a clumsy man in a lizard suit, and a number of over-the-top actors who seem to be trying too hard to convince the audience of the creature’s dangers.

That stereotype, however, was created by the 1956 American cut of the original Japanese film. The American cut was titled Godzilla, King of the Monsters! For the American version, the producers had removed more than 16 minutes of footage and replaced it with a subplot involving an American journalist witnessing the giant monster’s rampage across Tokyo.

In addition to this, the film was poorly dubbed in English, which influenced the reception significantly, as the actors looked silly while being out of sync with the voice-over.

But what really downsized the quality of the original motion picture, directed by Ishiro Honda, was the censorship of its explicit subtext, which dealt with the devastating effects of atomic weapons―effects to which the Japanese were introduced to a decade prior to the release of the original film. The original version became a landmark of kaiju―Japanese film genre featuring giant monsters as main antagonists.

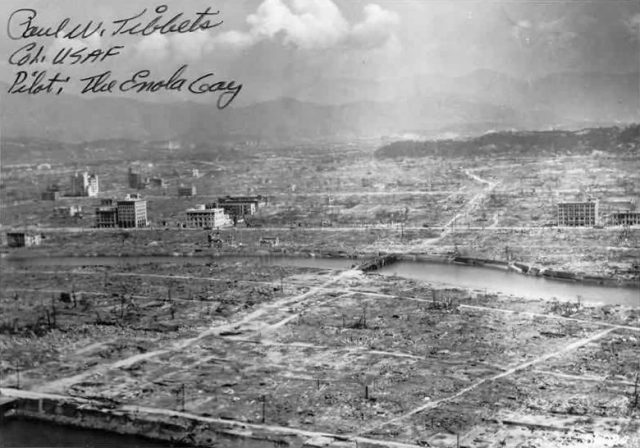

Having witnessed the destroyed city of Hiroshima one year after the atomic bomb was dropped, Honda became captivated with the idea of such destructive power in the hands of men.

Even though Honda was determined to commemorate the disaster that struck Japan in 1945 and brought World War II to its end, the immediate post-war years made it impossible to address the matter directly. Censorship, endorsed by the American forces occupying Japan, forbade film directors and artists of other sorts to portray contemporary topics, and, most of all, to be critical of the American military presence.

This meant that the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki were almost taboo, especially in the period between 1945 and 1952. Concerning the subject of censorship in Japan, Claude Estebe, a visual culture scholar from France, gave a comment for the Bangkok Times in 2012: “Japan was occupied by the U.S. army until September 1952. During this period there was a ban imposed by American forces on information about the Hiroshima and Nagasaki nuclear bombings and their aftermaths—namely the radioactivity-induced diseases.”

But since the initial development of nuclear weapons, the Cold War dictated that the research must go further. The second generation of nuclear weapons was already on its way, and it needed to be tested. In 1954, the U.S. Army conducted tests of its hydrogen bomb in the Pacific Ocean. At the same time, a Japanese fishing boat called Lucky Dragon 5 was caught up by a wave of radiation released from the blast.

The crew was poisoned and suffered acute radiation syndrome (ARS). The boat’s chief radioman, Aikichi Kuboyama, subsequently died from the poisoning. Luckily, other crew members managed to recover. Nevertheless, the incident sparked a strong anti-nuclear movement in Japan, especially because, after the event, rumors started circulating that contaminated fish had entered the market.

In addition to this, the Soviet Union was also testing its own nuclear weapons on the far northeast section of the country. The Japanese were caught between two fires.

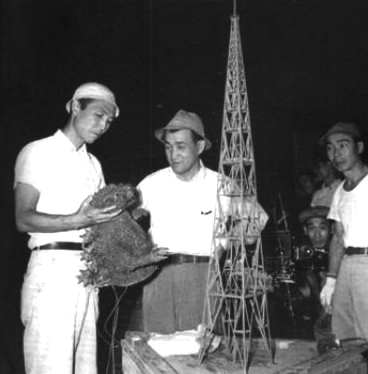

Under such circumstances, Honda decided to make his vision come true. He conceived of a giant monster, awakened from the depths of the ocean by the power of these nuclear tests. The monster itself would have enormous strength and would breathe fire while leaving a radioactive trace to contaminate the survivors of its rampage.

Honda called it Gojira―a mixture of the Japanese word for a whale (kujira), and the English word gorilla, which was a clear reference to King Kong. Since the occupation was over in 1952, the censorship was losing its power. That didn’t mean the authorities weren’t worried about Honda’s script, but since the film would fall into the science fiction genre, they misjudged its allegorical potential.

The result was a truly bleak and disturbing picture. Images of destroyed buildings, homeless people, stretcher bearers carrying dead and wounded together with an unstoppable force of nature in the form of a giant lizard invoked memories of the devastation the country had gone through after a war that began with Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, in Hawaii and included atrocities committed by Japan.

In the film, a Geiger counter runs wild while approaching a child who survived the attack. In one scene, a woman holds her two infants as the monster approaches, telling them they would soon be joining their father, who most probably died in the war.

These scenes are naturalistic and brutal. Scenes of radiation poisoning and the destruction of lives re-created the sense that the ghosts of the war still haunted Japan and that in order to move forward, one must be at peace with the past.

Apart from the two atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945, many major cities including Tokyo were targets to extensive bombing campaigns that caused enormous material damage and the killing of between 241,000 and 900,000 people. All of Japan has seen its fair share of destruction and only nine years after the war, the scars were still fresh.

This is why Honda’s film made such a huge impact. This metaphorical layer of Gojira sparked a debate on the potential dangers of scientific progress. In the film, a scientist character devises a weapon of such destructive power that he becomes scared of its misuse. Even though he lets the device be used on taking down the monster, he burns all of his notes and eventually commits suicide so that the weapon could never be used again.

This act clearly illustrates Honda’s opinion on the use of science in military purposes that was shared by many of his countrymen. His decision to create a monster so cruel and unsympathetic towards anyone―including women, children, and the old―indicated that Godzilla was more of a god than a monster.

Related story from us: The mystery of the Vela Incident: some say it was a secret nuclear explosion

In 2004, when a restored version of the film finally reached the United States, the viewers were stunned. The film clearly wasn’t just entertainment, but a testament to the suffering that the Japanese endured. Numerous other versions, remakes, knock-offs, and sequels were made after 1954 original, but none of them hold such effective critique and significance as Ishiro Honda’s Gojira.