The nuclear-arms race of the Cold War era, particularly when “fought” between the two superpowers, the United States and the Soviet Union, nearly brought humanity to the brink of disaster. Both were producing and stockpiling like mad at the time and the whole world was living under the threat of global destruction, hoping their leaders would stay cool headed and not do anything crazy.

And in more than one instance, temptations led to so-called nuclear close calls, incidents that could have ended the world as we know it. The fate of the planet was hanging by a thread and some of these nuclear disasters or near misses are well known and thoroughly documented; while others remained hidden for an investigative mind to explore.

One such radioactive disaster occurred in a far off place, deep in the Ural Mountains in the Soviet Union, on September 29, 1957. The closed town of Ozyorsk (Chelyabinsk-65) had in its vicinity a highly active Plutonium production plant.

A nuclear explosion on that day at the Mayak Production Association plant had a rating on the INES scale (International Nuclear Event Scale) of Level 6. To put this in perspective, the Chernobyl and Fukushima nuclear disasters were rated INES 7; this makes the Mayak nuclear explosion highly critical, yet it remained shrouded in mystery for decades.

The Soviet Union of the time was an extremely secretive and uniquely political communist regime, as well as an utterly terrifying dangerous place for foreigners.

The small town of Mayak was a closed city and was not marked on official maps. It was simply referred to as Chelyabinsk-40, distinguished by the last two digits of its postal code attached to the area where it was located, Chelyabinsk, nowadays listed as one of the most contaminated places on earth.

The Mayak nuclear plant and the city Ozorusk built around it were primarily covert operations, with the intention to produce “under the radar” the first Soviet nuclear bomb and catch up with the Americans. Western spies were always on the hunt, looking for military or other strategically significant maps; for the Soviets, it was highly critical that the West stay in the dark about the Mayak Plant.

After fighting alongside the U.S. and Europe against Hitler and the Axis powers in the Second World War, the U.S.S.R. leadership quickly realized that the West had no intention to, in any way, prolong the relationship and hastened to file for divorce.

This quick breakup took its toll on Soviet technology; the Soviet Union was ahead in the space program, but Russian nuclear scientists and engineers were way behind in the modern nuclear know-how, hence keeping up with the U.S. in terms of nuclear arms became a daunting challenge for them.

This sense of defeat ushered in an era of rapid production of weapons-grade uranium and plutonium. The U.S.S.R. could not afford to seem weak in any way and deployed all their resources to flex their muscles at Europe and America.

The construction of the Mayak plant was an ambitious project by the Soviets, which took only three years; from 1945 to 1948 engineers erected a plant in such haste that even the most integral elements, such as an adequate cooling system, were complacently overlooked. The authorities paid no heed to the environmental aspect of the plant, paving the way for the future disaster.

Soon after the plant was made functional in 1948, Mayak, within a year, produced the first Soviet nuclear bomb. But Moscow wanted more and quickly. The hastened process on top of the total disregard for basic safety regulations led to a large amount of high-level radioactive waste being drained into the nearby Tech River (“Russia’s Radioactive River”), which then flowed into the Ob River and to the Arctic Ocean. The surrounding lakes that were used as a natural cooling system for the plant’s six nuclear reactors also became heavily contaminated. Lake Kyzyltash, for instance, was more of a toxic waste dump than it was a lake. And Ozyorsk was built right on its shores.

The level of contamination soon became highly critical and raised alarms in the nearby population. Workers were receiving radiation overdoses, and the radioactive waste dumped into the lake and the nearby river from 1949 to 1952 caused breakouts of radiation sickness on several occasions in the city and the villages down the stream.

In 1953, Soviet officials decided to undertake special safety measures to contain the tons of waste produced by the plant. The idea was very basic and not much attention was paid to ensure adequate levels of protection.

Large steel tanks were built and these were buried 25 feet underground. To keep the temperature under control, additional coolers were built around the banks. At the outset, it seemed as if the whole idea of building the tanks was to stop the waste from ending up in the waters.

The first indicator of the impending disaster appeared when, in 1956, one of the containers started heating up; the situation was ignored by the engineers, partly because it was nearly impossible to track it. The maintenance infrastructure was weak and the measurement system was inadequate, so the temperatures kept on rising and reportedly other containers also started reaching critical levels.

Then, in 1957, the tipping point was reached. The temperature inside the tanks hit about 660 degrees Fahrenheit, triggering an explosion equivalent of at least 70 tons of TNT ripping through the plant, devastating the site and its immediate surroundings, sending a plume of 20 million curies of radioactive fallout into the air, including large amounts of strontium-90, and long-lasting cesium-137. Almost 40 percent as much radioactivity was released at Kyshtym than was flung into the air over Pripyat during the Chernobyl disaster 20 years later.

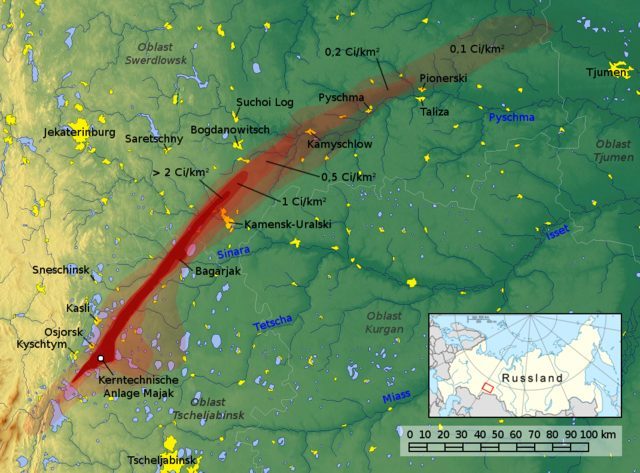

In the next 11 hours, the bluish-purple radioactive cloud emerging from the epicenter of the explosion reached, and contaminated, approximately 7,720 square miles of mostly inhabited land, creating a contaminated region now known as the East Urals Radioactive Trace (EURT), which at the time was home to 270,000 people.

By the time the cloud dispersed, it had already severely affected some 22 villages, causing a massive health and population crisis. The authorities did not even bother informing the locals of the reason for the gradual evacuation from these villages over the next two years of only 11,000 people. There were a number of conspiracy theories about the chemical disaster, one of which that the slow pace was intentional so the government could measure potential effects of the radiation. They disclosed details to no one outside and opposed every compensation claim for the disastrous event for 20 years.

During those years, the closed town of Ozyorsk (renamed in the early 1990s) could never be found on a map and, according to the Soviet Union, it never existed. So the disaster was named after the next known town of Kyshtym in 1976, when actual details about what had happened left the Soviet border for the first time thanks to biologist Dr. Zhores Medvedev and his published accounts of the catastrophe in the British Journal New Scientist.

His claims were backed by a fellow scientist and Soviet descendant, Lev Tumerman, who reportedly drove through the Chelyabinsk area, which was nothing more than a dead zone. There were no people, no houses, no farms, no nothing. Only signs urging people to drive as fast as they can down the road and never stop. Later on it was revealed that the American government and the CIA had official information about the event, and even had actual footage from back in 1960, but supposedly decided to keep quiet and not put their own nuclear program at risk.

The final death toll of the Kyshtym Disaster can never be known; however, a number of independent sources claim that fatalities must have been upwards of 10,000. Not by the explosion and the initial exposure alone, but due to a long period of toxic poisoning, both prior to and for decades after the event. Chronic radiation poisoning from the nuclear waste discharge caused high rates of cancer and genetic disorders among the people of the region.