Despite the widely accepted theory that the black rat (Rattus Rattus) was the main culprit of the plague pandemic that devastated 14th century Europe and Asia, scientists from the University of Oslo, Norway, and the University of Ferrara, Italy, beg to differ.

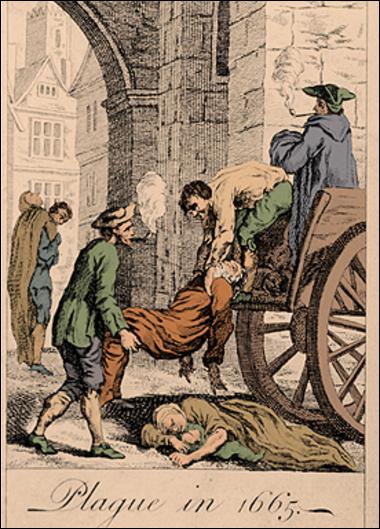

The Black Death, as the bubonic-plague pandemic was dubbed due to its enormous mortality rate, reached its peak in Europe in the period between 1346 to 1353, when almost one-third of the continent’s population was wiped out by the disease. The death rate in Europe, Russia, and the Middle East is believed to have reached between 75 million and 200 million people.

This disease of apocalyptic proportions was at first considered a form of God’s punishment or an astrological catastrophe. The initial idea was that sickness was being spread via poisoned air. The lack of comprehension of medicine and widely held superstitions triggered a number of pogroms of Jews in Europe and other foreigners who were considered the bearers of the disease.

It was not until the end of the 19th century that a Swiss-French scientist, Alexandre Yersin, produced a theory that the fleas carried by rats were responsible for the spread of plague among humans. It was the 19th century when hygiene was first considered a vital factor in spreading the virus.

Yersin came to the conclusion after studying an outbreak of the disease in China and India in the mid-19th century. In 1894, in Hong Kong, Yersin isolated the bacterium responsible for bubonic plague, which was subsequently named after him―Yersinia pestis. During the same time, a Japanese scientist, Kitasato Shibasaburō, managed to isolate the same bacterium, but the honor of naming it fell to his Swiss counterpart.

The theory became widely accepted, even though it was questioned on numerous occasions. Alternative explanations arose during the course of the 20th century, but they all were dismissed due to lack of evidence.

Today, a joint effort conducted by Norwegian and Italian scientists might just give us the answers we need on the mystery of the Black Death and its incredible and devastating reach.

They suggest that the source of the disease wasn’t the rat, nor was it the flea which inhabited the rat. The scientists from Oslo and Ferrara blame humans for the spread of illness. More precisely, their research demonstrates that the parasites that dwell on humans themselves, spreading from person to person, were the bearer of the plague that decimated Eurasia, without the rat serving as the intermediate.

They explain their research in a paper published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Science: “Here, we show that human ectoparasites, like body lice and human fleas, might be more likely than rats to have caused the rapidly developing epidemics in pre-Industrial Europe.”

The methodology that the researchers used included both the rat theory and the airborne transmission theory (which originated in the Middle Ages), with the addition of their own proposal that the pandemic was caused by fleas and lice residing on humans and their clothes rather than animals.

They then produced models on how the disease would spread by these three methods, and applied and analyzed it using the mortality data from nine plague outbreaks in Europe between the 14th and 19th centuries.

The simulation was made in order to construct models of the disease dynamic. Soon, the assumption that the human fleas and lice were responsible proved in seven out of nine cases to best match the pattern. Professor Nils Stenseth of the University of Oslo concluded in an interview with BBC News that the lice model fits best: “It would be unlikely to spread as fast as it did if it was transmitted by rats. It would have to go through this extra loop of the rats, rather than being spread from person to person.”

Professor Stenseth added, stressing the significance of such studies, that: “Understanding as much as possible about what goes on during an epidemic is always good if you are to reduce mortality [in the future].”

Since plague is still endemic in some countries in Asia, Africa, and America, Stenseth points out the significance of hygiene in general as the main prevention of an outbreak.