The late 1920s and 1930s were the golden age of airships, lighter-than-air aircraft also known as dirigibles or zeppelins. At that time, entrepreneurs across the world were convinced that airship design had been perfected and many people saw these colossal flying balloons as the bright future of air travel.

Even the Empire State Building, which was finished in 1931, was equipped with a dirigible mast because its creators believed that it would serve as a docking bay for transatlantic airship flights. Sadly, airships quickly turned out to be a dangerous and extremely unreliable form of travel. Aside from their navigation system being clumsy, they were usually filled with hydrogen, a flammable gas which was responsible for a number of deadly airship accidents.

On May 6, 1937, the infamous German airship Hindenburg, one of the largest airships ever built, attempted to dock at the Lakehurst Naval Station in New Jersey. If the docking had been successful, Hindenburg would have completed her first transatlantic voyage.

Unfortunately, the airship’s hydrogen reservoir caught fire and the craft crashed to the ground, killing 36 of the 97 people on board, as well as one crewman on the ground. Since Hindenburg‘s arrival was anticipated with much excitement, the site of the disaster was teeming with reporters and camera crews who didn’t hesitate to film the accident: in a matter of days, newspapers across the world were filled with horrifying photographs of the burning aircraft and the dream of airships becoming a prominent commercial form of travel was abruptly shattered.

Due to the media attention which surrounded the Hindenburg disaster, its demise is often cited as the worst airship accident of all time. However, there were actually several airship accidents with fatalities that greatly surpassed the death toll of the Hindenburg tragedy.

The deadliest of these events was the U.S.S. Akron disaster, an accident which occurred on April 4, 1933, and resulted in the deaths of 73 people on board as well as two people aboard another airship which came to Akron‘s aid.

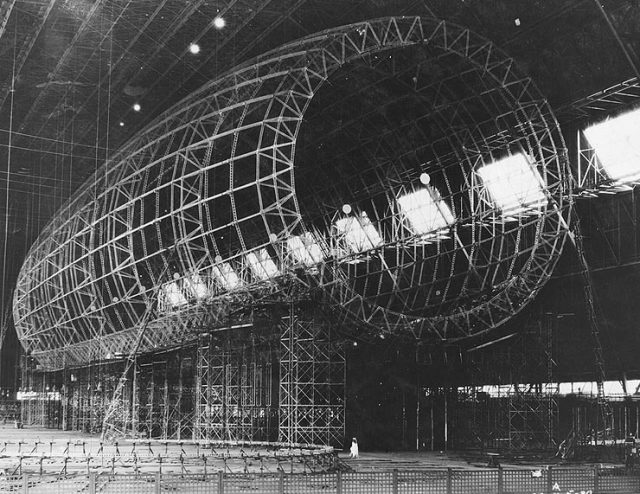

U.S.S. Akron was a massive aircraft, almost as long as Hindenburg, which could carry up to 120 passengers and crew. It was built as a flying aircraft carrier so it was able to carry up to five F9C Sparrowhawk fighter planes, which could be launched and recovered while the airship was in flight. Unlike the Hindenburg, which was filled with hydrogen, Akron was filled with helium, a non-flammable gas which prevented the craft from catching fire in the event of an accident.

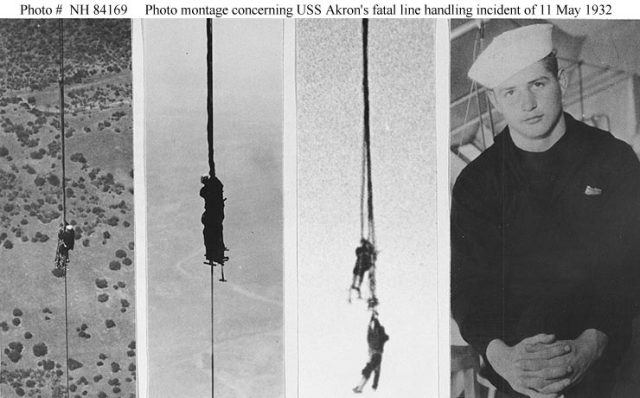

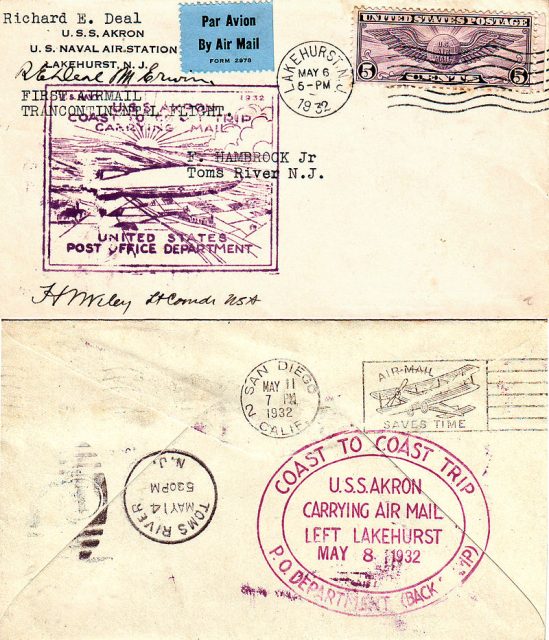

From its launch in August 1931 until April of 1933, when it perished, the airship was extensively used for scouting missions. Although it experienced two minor accidents during that time, the craft was considered stable enough for further military use.

On April 3, 1933, Akron was tasked with the calibration of radio equipment along the New England coast. As she flew over Barnegat Light in New Jersey and proceeded towards the ocean during the night, the weather conditions gradually worsened and a light breeze turned into a full-scale Atlantic storm.

The 785-feet long airship managed to maintain its course for a while, but the harsh weather soon dismantled its navigation system. Akron plunged into the ocean. It quickly broke apart and the crew ended up in the hostile water; 73 people died within minutes of the crash.

A German merchant vessel which witnessed the airship’s descent rushed to the crash site and managed to retrieve three survivors. By the time the vessel arrived, Akron had already been swallowed by the ocean. A smaller airship, the J-2, was immediately deployed to search the area for more survivors but the harsh weather caused it to suffer the same fate as the U.S.S. Akron. The crew lost control of the craft and it crashed into the ocean, killing two of the seven people on board.

A total of 75 people lost their lives in the U.S.S. Akron disaster, making it the worst airship disaster in history. Since the wrecks of both airships quickly sank to the bottom of the ocean and no reporters were present on site, the authorities were able to downplay the incident and the public of the time wasn’t made aware of the true scope of the catastrophe.

Nowadays, an outrageously small and weathered metal plaque coupled with a tiny peace of debris from the airship commemorates the event in Manchester Township in New Jersey. Sadly, the memorial doesn’t even list the number of men who lost their lives in the disaster.