Julius Popper was a mechanical engineer, an adventurer, and a bounty hunter targeting the Selk’nam people of South America. It was the last for which he is known today–the Selk’nam genocide. Although it was all colonial business, Popper is the person held most responsible for the extinction of one of the last indigenous groups in South America, along with their unique culture and language. It took place during the time of gold mining fever in Patagonia, when many people arrived seeking their fortune, regardless of how they acquired it.

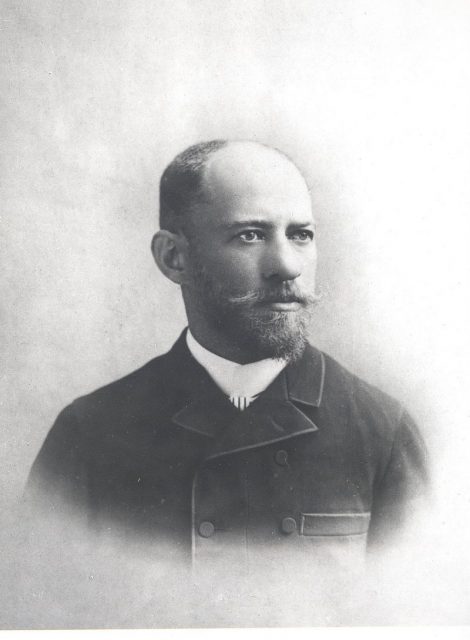

Popper was born to an Argentine-Romanian family in Bucharest. His father, Neftali Popper, was a professor and antique merchant. It was probably his father who sparked the curiosity for traveling and exploration in Julius. As soon as he could leave home, Popper moved to Paris, where he studied mechanical and civil engineering. Once he graduated from university, this “natural born explorer” was off to see the world.

He started with Turkey and Egypt, and then India, China, and Japan. He journeyed through the Americas, from north to south. He is considered by some sources to have designed the modern outline of the city of Havana, Cuba. In 1885, while he was exploring Brazil, he heard about the gold rush in Argentina and quickly headed for Buenos Aires. From there, Popper made his way to the mining camp at Cape Virgin. He realized that poorly planned and aggressive mining were exhausting the land, so he established his own mining exploration company in order to find his own claim.

Popper led the 18 men of his company, Lavaderos de Oro del Sud, which in English means the Gold Washers of the South, on an expedition to the archipelago of Tierra del Fuego. They landed at San Sebastian Bay in the latter part of 1886 and established the settlement El Palermo. The company had its chief engineer, mineralogist, photographer, and journalist, and was well equipped with weaponry to protect the gold from claim jumpers. Within a year, the Gold Washers company mined 154 pounds of gold, which ensured Popper’s wealth and status.

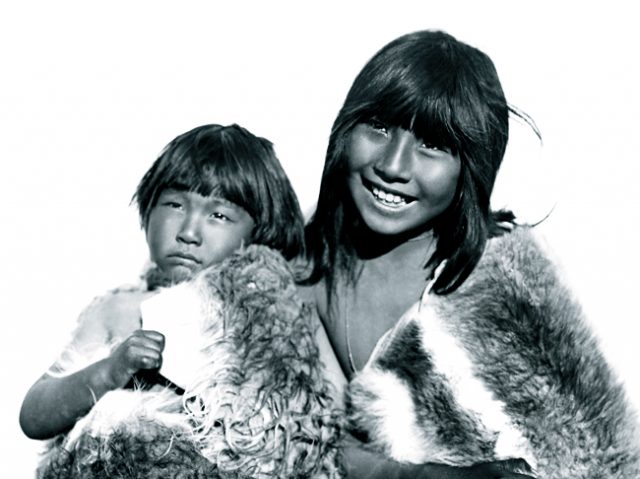

But relations with the island’s natives did not have the same success. From the day of their arrival, Popper and his men clashed with the Selk’nam, who lived a nomadic hunter-gatherer lifestyle and were unable to comprehend the activities of the newcomers. The Selk’nam people didn’t have any concept of land or animal ownership, nor understanding of agriculture or the desire for gold. They hunted mainly guanaco (a type of llama) and fox, moving along Tierra del Fuego as the changing seasons dictated hunting and foraging possibilities.

Genetically, the Selk’nam were closer to the Australian Aborigines than to the northern Native Americans, it is believed. Although they were considered by the immigrants as a simple race, the complex spiritual beliefs of the Selk’nam indicate that their society was far from primitive.

They lived peacefully until ranch settlers, cattle breeders, adventurers, and the infamous gold-prospectors arrived from the north of Argentina and Chile, the United States, and the U.K. The settlers treated the natives with a complete lack of respect for their manner of living, and for their land. And when farmers placed sheep on their traditional hunting grounds, the Selk’nam saw nothing wrong in hunting this easy prey, which obviously caused friction between the native people and the ranchers.

There were reputedly financial rewards for the head of each native, and many succumbed to imported diseases such as tuberculosis, smallpox, and scarlet fever. Those who managed to survive the genocide and diseases were forced to religious conversion by Christian missionaries, and others were brought to Europe to be exhibited as curiosities in the human zoos that were popular at that time.

Julius Popper was maybe the most bloodthirsty and brutal hunter of the Selk’nam. The number of people he killed, directly or indirectly, is not known, but his determination to hunt down the natives seems to stem from the initial conflicts between them and his men. Popper established his own private army as a protection from thieves, and instructed these men to kill any natives who roamed into the mining areas. His forces even saw off a challenge mounted by the Chilean government in 1889, who weren’t fond of his success and power in Patagonia.

To symbolize his power, Popper issued his own coins and stamps. And after the stock market crashed in 1890, causing the Argentinian peso to lose its value, Popper’s gold coins were used as currency. His status and financial power allowed Popper to appoint himself as the ruler of Tierra del Fuego–he even made preparations for an expedition to Antarctica, where he wanted to enforce the Argentine claim in certain parts. At some point, Popper moved his minting operation to Buenos Aires.

In the summer of 1893, at the age of 35, the young and ambitious explorer was found poisoned in his apartment in Argentina’s capital. It took nobody by surprise, as he had made a lot of enemies. There is speculation that he was poisoned by some of the surviving natives of Tierra del Fuego, although, most likely, his murder was inspired by business envy.

Before their first contact with Europeans, there were around 4,000 Selk’nam people living in Tierra del Fuego, and in a few years there were only 100 left. The last full-blooded Selk’nam tribesperson, Ángela Loij, died in 1974, and the last person speaking the Ona language died in the 1980s.

Today, there are few hundred people who identify as Selk’nam descendants. As for Julius Popper, he is the subject of several books, and there is an Argentine rock band named after him. One of his mints, built to manage the gold, was adapted to house the Museo Territorial.