Today’s art world is striving to address the gender imbalance which, for quite a long time in history, promoted male artists. The creative works of Marina Abramovich, Yayoi Kusama, Tamara de Lempicka, Frida Kahlo, and a myriad of other acclaimed female artists are presented shoulder to shoulder with the works of their male colleagues in a number of museums around the world.

Women artists once struggled their whole careers for acknowledgment. Among them was a non-conventional artist from the 1930s named Méret Oppenheim, one of the central figures in the Surrealism movement. The fierce Oppenheim traced the path for other female artists when the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) accepted and displayed her sculpture “Object,” thus introducing the first work by a female artist in its collection.

This revolutionary art story began when Oppenheim, an 18-year-old Swiss art student from a progressive intellectual family, arrived in Paris to study at the Paris Académie de la Grande Chaumièrs. The sociable young woman with “the wit of a scientist and the looks of a movie star” quickly befriended the Surrealists Andre Breton, Marx Ernst, and Man Ray, as well as other notable artistic figures such as Picasso and Giacometti.

All of these artists were at least twice her age but were captivated by her presence. For some time she served as their model and muse, mostly posing for Man Ray and his Erotique Voilée (1933). In 1933, Surrealism provided an opening for Oppenheim’s career, allowing her to exhibit her sculptures and canvases with her male peers. Soon, her primary function as an inspiration for the artists was replaced by the launch of her career in which she focused on exploring female sexuality, identity, and their exploitation, challenging the established social image of femininity.

Oppenheim’s interests as an artist gravitated mainly around household objects which were associated with feminine domesticity, transforming them into erotically suggestive assemblages. Her best-known work is Object, also known as Luncheon in Fur or Breakfast in Fur, and according to Artsy, it was inspired by an intriguing encounter at the Parisian Café de Flore, the favorite haunt of local artists during the 1930s. Oppenheim scheduled lunch with Picasso and his lover, Dora Maar, and when she showed up at the restaurant, they were immediately captivated by her unique stylish accessory–a bracelet swaddled in fur, made by the famous jewelry designer Elsa Schiaparelli. At one point Picasso made a cheerful comment that maybe all things could be covered in fur. Reportedly, Oppenheim pointed to the cup on the table and said in a humorous tone: “Even this cup and saucer. Waiter, a little more fur!”

The light-hearted chit-chat about a fur-lined tea set haunted Oppenheim after the meeting. Next thing, she bought a cup, spoon, and saucer at a store and covered the three elements with some pelt whose type is still not firmly established.

Finally, her Object was created. Since its first public presentation, the work sparked curiousness and controversy among artists and art connoisseurs. Oppenheim explained it as a combination of domesticity (tea set) and animality (fur). According to Artsy, it was first revealed in public at Andre Breton’s show “Exposition Surréaliste d’Objets,” in Paris, displayed on the bottom shelf of a vitrine, under the works of Picasso, Duchamp, and Ernst. Nevertheless, the fur objects caused enough excitement to overshadow the rest of the Surrealists works based on a uniting idea–objects as visual jests with a total impracticability.

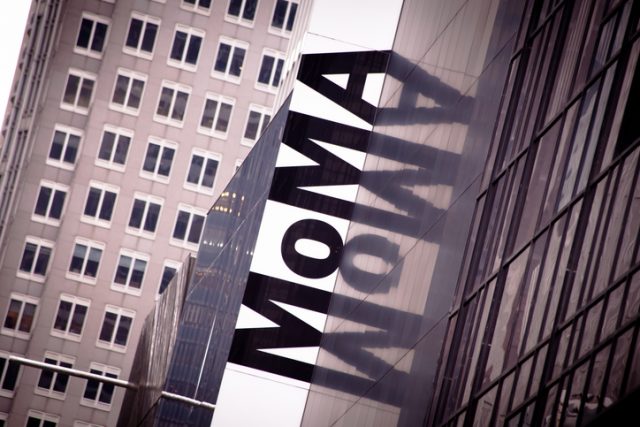

The sculpture traveled to London for display at the International Surrealist Exhibition and then arrived in New York. The MoMA’s director Alfred H. Barr, Jr. recognized it as a new Surrealistic expression and knew that the bizarreness of the fur breakfast would likely attract audience attention.

He added the Object in the “Fantastic Art, Dada, Surrealism” survey which was dominated by works of male artists (39 of the 46 in total). Barr was right. The New York audience loved it and although some critics rejected and even ridiculed it, no one could deny its popularity. Regardless, MoMA’s officials refused his suggestion to adding it to the museum collection. Barr didn’t want to let the precious work escape from his hands and so he bought it. In 1946 he finally managed to sell it to MoMA.

At first, the sculpture was viewed only by appointment and had to wait until 1961 for its public, institutional display. At present, Object is among MoMA’s most recognizable works, witnessing the history of subversion of the male-dominant Surrealism and its significant role in the creation of a new form of female identity.