Among all the incredible stories of hoarders and recluses, the story of Ida Wood might trump them all. She was a wealthy socialite in New York in the late 19th century–before she locked herself in a two-bed apartment in the Herald Square Hotel, never going out and never spending more than a few pennies a day. When she was forced to leave the room, at the age of 93, bonds and stocks worth tens of thousands of dollars were found hidden in shoeboxes. She also hid expensive jewelry, including several diamond necklaces stored in cracker boxes. As for cash, Mrs. Wood had some $500,000 in $10,000 dollar bills pinned to the inside of her nightgown.

In March 1932, the mysterious resident from suite 552 at the Herald Square Hotel in New York City got in touch with the rest of the world. It was Ida Wood, crying for help as her sister was dying–the first time that the 93-year-old had voluntarily opened the door in 24 years. Before long, the reclusive woman was joined by the hotel manager, along with a physician and an undertaker. Ida’s sister, Mary E. Mayfield, was lying dead on the couch covered with a sheet. But it was the room that amazed the visitors. Crammed with piles of yellowed newspapers, several large trunks, an improvised kitchenette in the little bathroom, hundreds of cracker boxes, and stacks of old wrapping paper.

Ida was old and in poor health, and lawyers were brought in to investigate the case. Although she claimed that she was poor, a large amount of wealth was discovered among the trash in her room, in bonds and stocks, jewelry, and cash. The discovery of this Tutankhamun-tomb-like hotel room made the newspaper headlines around the country: “RECLUSE, 93, HOARDING MILLION DEFIES TREASURE SEARCHERS”

The Brooklyn Standard Union reported: “A frail but spirited little lady of 93 years, once the belle of mid-Victorian days, today stomped her defiance of searchers spurred by discovery of nearly a million dollars in currency she hoarded in her hotel room ‘because she was afraid of banks’ ”

The case sparked the curiosity of lawyer Morgan O’Brien Jr., and he began investigating. He found out that the hotel manager of seven years had never once seen Ida Wood or her deceased sister, and somehow they always paid their bills in cash. According to the hotel’s records, the sisters, along with Ida’s daughter, Miss Emma Wood, had moved into the two-room suite in 1907. A future investigation revealed that Emma Wood, who had died in 1928, at the age of 71, might have been Ida’s youngest sister, whom she presented as her daughter.

The hotel’s maids said that regardless of their efforts to at least change the bed sheets, the staff only managed to pass clean towels and sheets through a crack in the door as the sisters denied anyone’s entering their kingdom. In his interview with the bellhop, O’Brien learned the eating habits of the sisters –through the years they were always asking for the same items: crackers, eggs, bacon, coffee, and evaporated milk, and sometimes fish. They prepared their meals in their makeshift kitchenette. Sometimes Ida requested Havana cigars, Copenhagen snuff, and jars of petroleum jelly, which she apparently massaged onto her face, daily, for hours. The bellhop claimed that each time he received a tip of 10 cents from Ida, who was always telling him that money was the last thing she had.

But so much wealth and such isolation didn’t make any sense. It was clear that Ida Wood was a recluse, a miser, and a hoarder, but her history seemed even more intriguing to O’Brien. Digging into her past, he found out that Ida Wood was a New York socialite, the wife of deceased congressman Benjamin Wood who had owned a shipping business and the New York Daily News (not the same that runs today). His brother was Fernando Wood, former mayor of New York City. Benjamin was married to his second wife when he began an affair with Ida, 17 years his junior.

One day, Benjamin Wood received a curious letter from a girl who later claimed to have aristocratic blood as the daughter of Louisiana sugar plantation owner, Henry Mayfield, and Ann Mary Crawford, a descendant of the Earls of Crawford.

“May 28, 1857

Mr. Wood—Sir

Having heard of you often, I venture to address you from hearing a young lady, one of your ‘former loves,’ speak of you. She says you are fond of ‘new faces.’ I fancy that as I am new in the city and in ‘affairs de coeur’ that I might contract an agreeable intimacy with you; of as long duration as you saw fit to have it. I believe that I am not extremely bad looking, nor disagreeable. Perhaps not quite as handsome as the lady with you at present, but I know a little more, and there is an old saying—‘Knowledge is power.’ If you would wish an interview address a letter to No. Broadway P O New York stating what time we may meet.”

Now the reason why Ida proposed an affair through a letter to a man she has never met was that the two could never meet under ordinary social circumstances. Ida was neither rich nor noble, and neither was she named Ida Mayfield as she presented herself. She was born Ellen Walsh to Irish immigrants and raised in Massachusetts. As for Louisiana and her family relations living there, there were none. She probably never even visited the state. Young, beautiful, poor, and ambitious, Ellen left home at the age of 19 with a peculiar American dream, to become a New York socialite.

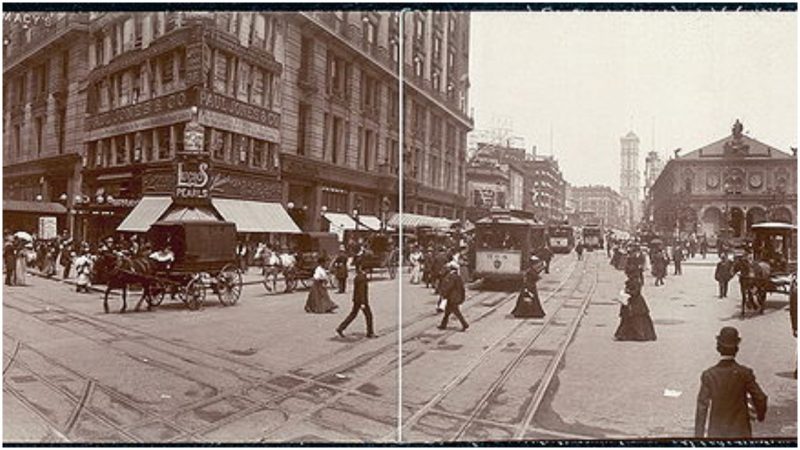

All Ida’s past was a foundation of lies. She began studying the relationships among the elite in the city through gossip and newspapers. She heard the name Benjamin Wood quite often, and, after learning that he had love affairs, she decided to become his mistress. Through the relationship with Benjamin, Ida easily entered the elite scene of New York. She was vivacious and lovely, and was always welcomed at the soirees and balls where she wore her expensive and dazzling jewelry. Ida met both candidates for president at the time, Abraham Lincoln and Democrat Samuel Tilden, and danced with Edward, the Prince of Wales. After a 10-year-long affair, when Benjamin’s wife died, the two got married.

Ida managed to turn every misfortune into her fortune. Literally. Benjamin Wood had a good income and was a generous philanthropist, but he did have one money issue and that was his gambling habits. Ida agreed with her husband that she wouldn’t interfere with his addiction, so long as he paid her every time he lost and shared half of the profits whenever he won. In that way, she was keeping the money safe. When he didn’t have cash, Benjamin put his property under Ida’s name. He got to the point when he asked her for some money, and she gave it to him in exchange for a controlling interest in his newspaper. She developed quite an interest in the newspaper and was writing for it for a while. Hence, Ida Wood became one of the first female publishers in the newspaper industry.

When Benjamin died in 1900, the New York Times wrote: “It was said yesterday that Mr. Wood possessed no real estate and that his personal property was of small value.” He’d put everything he had under Ida’s name. With her invented identity, Ida got more than she could imagine. She traveled the world, wore extravagant clothes and jewelry, had her own money and property in her name, was a respected socialite, and yet, ended up locked in a hotel room.

But then, instead of enjoying her wealth and status, Ida became paranoid about her possessions. Her mental state began to deteriorate, but it was mostly the financial panic of 1907 that overwhelmed her. She withdrew all the money in her name from the banks, sold her real estate, and she also sold the newspaper. With all that money (millions today), she moved to a hotel room with (most likely) her two sisters, where she remained for the next 24 years.