There is a certain irony in the elaborate beauty of Art Nouveau, one that sadly typifies our culture. It came from humble beginnings, from a defiance of the status quo of fat-cat factory owners raking in huge profits, but the workers producing the art were often faced with a poor standard of living.

The naturalism that defines Art Nouveau has its roots in the Arts & Crafts movement, a melting pot of art and philosophy that was opposed to the changes imposed on society by industrialism. People began to realize that small-scale homemade crafts that were produced with care and skill were being lost among the mass of factory-produced items.

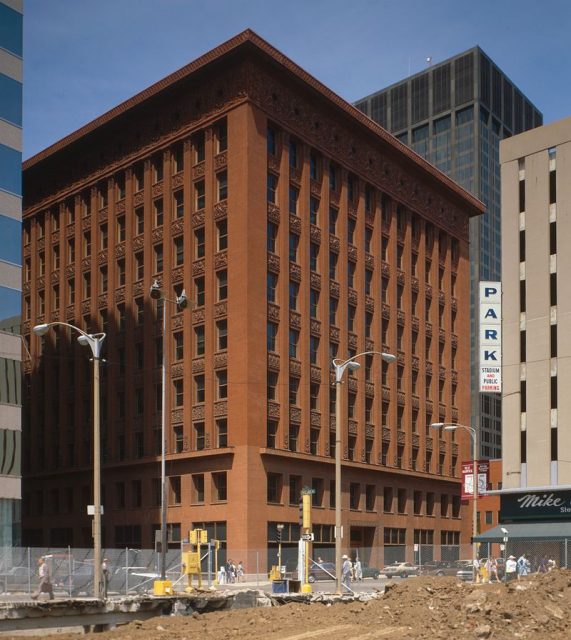

But, in the end, it became a status symbol for the rich and famous who could afford to pay for the finest materials and the top-rated artisans. The style was much less widespread in the United States than in Europe; Craftsman Style dominated in home design, and an upward trend in high-rise development was aided by the invention of a marvelous material called steel. But there are some Americans architects who made their mark in Art Nouveau history, such as Louis Sullivan, designer of the Wainwright Building in St. Louis, Missouri, who was a renowned champion of uniting form and function.

Art Nouveau came to life for me on a trip in Europe a few years ago, celebrating a milestone birthday. The first city lined up to visit was Prague in the Czech Republic, a country that turned out some of the most influential Art Nouveau artists, including Alphonse Mucha and Oskar Polívka.

Our sightseeing itinerary naturally took on an Art Nouveau theme–it’s pretty hard to avoid in Prague! Slowly the words in the guide book turned into eagerly gawking at buildings and peeking into hotel lobbies as we tried to decipher the architectural style without really having a clue, but I had found a new love.

From Alois Dryák and Bedřich Bendelmayer’s Europa Hotel in Wenceslas Square to the crazy Lucerna Passage (pure opulence plus an upside-down horse!), and everything in between; the only disappointment was that we didn’t have time to see the railway station building. The famous astronomical clock was left to play second fiddle.

After Prague came Venice, Italy, where a day touring Lido island, home of the Venice Film Festival, revealed some rather attractive Art Nouveau villas from the days when it was the place to be seen for the wealthy socialites of Europe. Inspired to go all out geek on the subject, I discovered there is a fascinating history behind this artistic style.

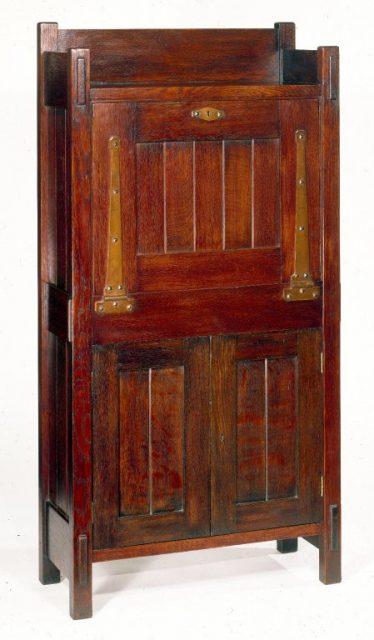

The initiative behind the Arts & Crafts movement was born from the impact of the Industrial Revolution and the desire to return to a more simple and idealistic way of life. While mechanization undoubtedly brought many benefits to society, there was a growing concern through the 1860s and 1870s about the loss of traditional skills and dangerous conditions that many ordinary people were now faced with in their workplace. Largely founded on the philosophies of John Ruskin, Arts & Crafts was first embodied in England, reaching the United States around 1890, where it also become known as Craftsman Style.

The movement took its influences from the natural world and medieval art, and applied them to a holistic philosophy of living, stressing the importance of human fulfillment from the connection of the craftsmen and -women with the creative process, thus it largely ignored the “high arts” of painting and sculpture, which were viewed as subjects of academia. Of course, in reality, no commercial venture is free from the capitalist drive for profit and the later years of Craftsman Style were dominated by machine production, for example, A. J. Forbes’ Mission Furniture.

It was from this artisan-made handicraft ideal, which aimed to quash the rise in poor quality, industrialized imitations of 19th-century artistic styles in the decorative arts, that we see Art Nouveau emerge in the 1880s and flex its sweepingly curved wings.

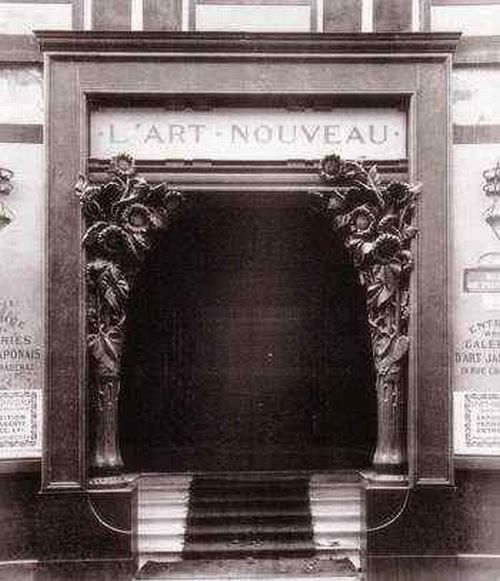

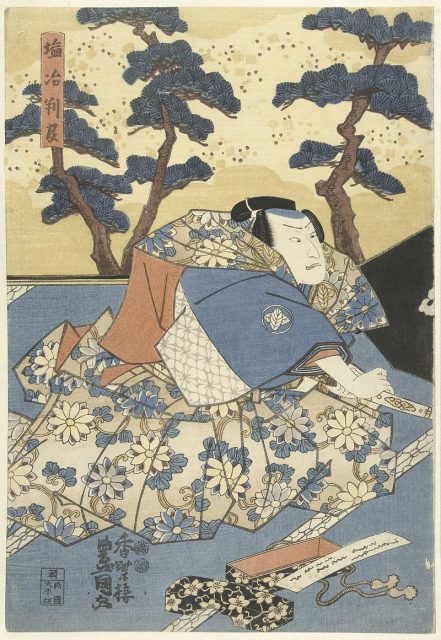

As the influence of the Arts & Crafts movement spread across Europe, it became entangled with other artistic styles, particularly the popular Japanese wood-block prints called ukiyo-e. Art Nouveau, meaning “new art,” was the natural evolution of this mix. It is said to have begun in Paris, in the gallery of Siegfried Bing, who showcased the work of young artists whom he inspired with the Japanese arts.

Despite sharing certain similarities, it left behind the rural nature of Arts & Crafts; both styles celebrated the unique qualities of handmade objects, but Art Nouveau introduced more elaborate, complex forms. It also came to be represented across a wider range of visual arts, including painting, sculpture, glasswork, and jewelry.

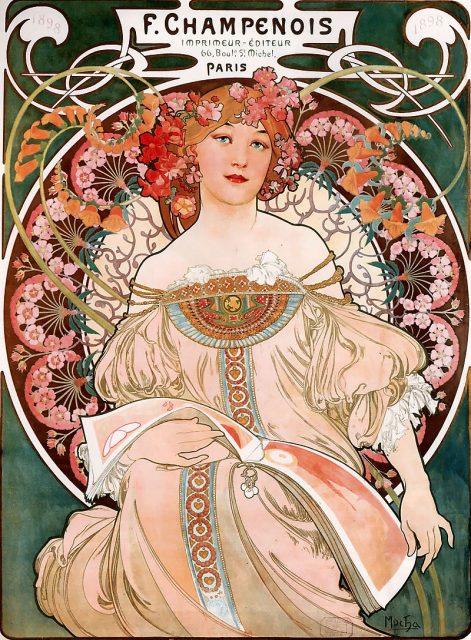

The distinctive style of Alphonse Mucha, a pioneer in the movement, demonstrates much of the Japanese influence in his use of calligraphic line forms, decorative patterns, and floral motifs (interestingly, Mucha’s work was, in turn, an inspiration for a branch of mid-20th century Japanese Manga art).

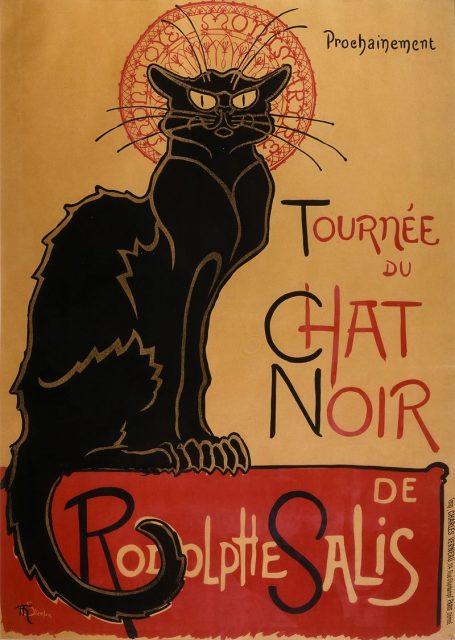

Drawing on a broad range of influences, including Romanesque and Islamic art, its main themes are organic symbolism–stems and blossoms of plants or decorative vine-like tendrils–united with geometric forms. Color schemes tend to be warm and muted; yellow was a favorite, but often in mustard or green-tinged shades. Art Nouveau architecture and interior design artists strove to create Gesamtkunstwerk, meaning “total work of art” or “universal artwork,” a word borrowed from 19th-century German philosopher of aesthetics Karl Trahndorff. In its essence, this meant everything would flow together. Columns grew into vines that curved gracefully around open spaces, or an abstract shell motif would be reflected in the shape of the window panels.

In the graphic arts sector, Art Nouveau’s application in novel printing techniques revolutionized magazine advertisements and established poster art as a reputable niche. The influence of the style on architecture was wide-reaching, as is still evident in many cities across the world.

It combined a variety of materials, with the incorporation of colorful tilework and natural wood trim as features. Art Nouveau buildings are typified by asymmetry, Japanese or plant-like embellishments, curved forms and arches highlighted by unexpected angles. To see Art Nouveau architecture at its most extravagant, check out the weird “individualistic” creations of Antoni Gaudi.

However, Art Nouveau is possibly best known as a style of interior design and furniture. Think hand-carved wooden pieces with irregular contours that seem to flow with the natural grain, or dado wall panels decorated with sinuous lines and repeated flower or feather patterns.

Colorful glass tends to be combined with iron in a way that brings to mind those traditional crafts but in a modernist presentation. Tiffany lamps are a still-popular example of the Art Nouveau concept of art and functionality.

Art Nouveau faded out in the 1910s to 1920s, however, it saw a resurgence in the ’60s and is still popular in many interior design magazines. Like anything, once you start looking for Art Nouveau, you’ll find it everywhere.