Can you imagine how creepy it would be to sail across the ocean and suddenly run into a ship drifting, unmanned and yet completely intact?

In all honesty, nothing compares to a scene such as that, really. The MV Lyubov Orlova, a long-lost abandoned cruise ship believed to be infested with flesh-eating cannibal rats heading right toward you might make for an even scarier scenario, but that’s another story for another time. Let’s focus on this other ship, and the mind-boggling mystery about its missing crew.

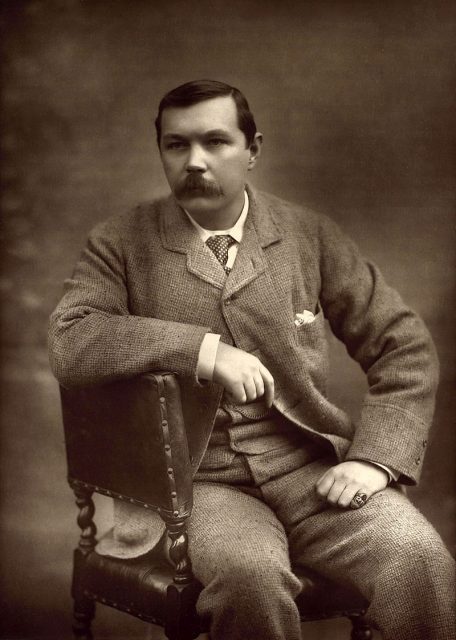

It has been tickling people’s imaginations for over a century. Sir Arthur Conan Doyle and Stephen King wrote about it, and many of us probably heard something about it. A whole century has passed, and still no one really knows for sure what had happened to those who boarded the Mary Celeste, probably the most famed of all the ghost ships.

The mystery is still very much not solved, and there are tons of plausible scenarios drifting around about what happened to the ship that set sail on November 7, 1872, from New York Harbor towards Genoa, Italy, and never reached its destination but was found abandoned “in mint condition” with everything intact–except for the men and the lifeboat.

Without survivors to tell the tale in detail, we offer some hard facts so you can try to decipher the solution for yourselves and decide what could, or couldn’t, have happened to the crew on board the Mary Celeste back in 1872.

According to nautical testimonies and maritime records, the 282-ton brigantine co-owned by James H Winchester, Sylvester Goodwin, and Benjamin Spooner Briggs, deemed seaworthy, insured, and loaded with 1,701 barrels of American alcohol (separately insured), began its journey from New York to Italy.

On board were Benjamin Spooner Briggs, one of the owners and the ship’s captain; his first mate, Albert Richardson; the captain’s wife, Sarah; their two-year-old daughter, Sophia; and the other six crewmen, all considered to be experienced and trustworthy. It was Captain Briggs’ first trip on the ship for which he bought shares earlier the same year, hoping to retire from the high seas and live a calm family life, earning money as a shipowner instead.

This was a try-out and Arthur, their seven-year-old son cared for by his grandmother (Briggs’s mother), was waiting for them back home in Rose Cottage, in Marion, Massachusetts. A few day before the journey, Briggs wrote his mother:

“My dear Mother…We seem to have a very good mate and steward and I hope I shall have a pleasant voyage. We both have missed Arthur and I believe we should have sent for him if I could…We finished loading last night and shall leave on Tuesday morning if we don’t get off tomorrow night, the Lord willing. Our vessel is in beautiful trim and I hope we shall have a fine passage but I have never been in her before and cant say how she’ll sail… Shall want to write us in about 20 days to Genoa…Hoping to be with you in the spring with much love. I am Yours affectionately, Benj.” – New York, Nov. 3d, 1872.

It was not Tuesday but Thursday when the ship sailed and the crew was last seen alive.

About a week later, another ship previously docked on the same harbor in New York, set sail to cross the Atlantic, the Dei Gratia or By the Grace of God. Both ships had similar routes, somewhat parallel paths, and one strange encounter on the open sea.

Scattered somewhere around 800 miles west of the coast of Portugal, nine larger volcanic islands and a whole bunch of smaller ones comprise what is today considered by many one of the “best-kept secrets” of the Atlantic. The Azores.

And not far from these gems of nature, precisely halfway between the Azores and Portugal, on December 5th, Captain David Morehouse, of the Dei Gratia, along with every single member of his crew, witnessed a strange sight: a ship at full sail was swinging wildly with the ocean waves. There were no signs it was guided by a man. Captain Morehouse recognized it as the Mary Celeste, but the ship was meant to be in Geneva by know. Realizing that something must have happened, they changed course to intercept the drifting vessel.

The ship was reportedly intact and empty. There were no signs of struggle, no explosions, nothing. Just a lifeboat missing and a crew that apparently left everything behind, including the captain’s journal. The cargo was there, the food was there, their clothes were, everything. It was as if the whole crew just vanished into thin air. Except for the ship’s chronometer, the celestial navigation book, and a log not entered in the captain’s diary of why they left the boat in such a hurry, everything was inside. The last entry said that after a long battle with a harsh storm they finally saw land in sight and were heading towards it. It was 5 A.M., November 25, 1872, and the land in sight was Santa Maria, one of the Azure Islands. In a strange twist of events, a crew that mysteriously went missing was last recorded heading towards one of the “best-kept secrets” in the Atlantic.

Captain Morehouse and his crew took the boat they found abandoned and sailed it to Gibraltar, for the ship was seaworthy and a reward was to be given to those who would find a lost ship at sea. He knew Captain Briggs personally, and that he was an adept sailor. He believed that something dire must have made him believe that the boat was about to sink, explode, or something of the sort.

The British Vice Admiralty Court called for a hearing to investigate if the finders were entitled to a reward from the insurance company. The ship was thoroughly examined and believed to be seaworthy but in very bad shape. A court statement reads: “The Galley was in a bad state, the stove was knocked out of its place, and the cooking utensils were strewn around. The whole ship was a thoroughly wet mess. The Captain’s bed was not fit to sleep in and had to be dried.” Moreover, they found one of the pipes to be broken, the ship’s floor flooded three and a half feet high in water, and nine of the barrels empty, as Captain Morehouse and his crewmen reported when they docked the ship in Gibraltar and asked for salvage rights.

Acting as Attorney General for Gibraltar in the investigation, Frederick Solly-Flood, who actually was an Advocate General for the Queen in Her Office of the Admiralty, made sure to accuse everyone of everything; even Briggs himself as an accomplice in an insurance fraud, but in the end, after more than three months, not a shred of evidence of foul play was found and Sir James Cochrane, the Chief Justice of Gibraltar presiding as judge in this specific case, “cleared the men of all charges” brought upon them and granted them salvage rights in accordance with maritime law. According to him and the investigation conducted, the crew left the ship in a hurry in a state of panic.

The story continues to intrigue people a century and a half later after the “Mary Celeste” was discovered, with the crew missing and one of the recently refitted ship’s pumps dismantled in the flooded hold. A letter from the 1940s confirms that “harsh stormy conditions prevailed in the Azores on the 24 and 25 November 1872″ – Servico Meteorologico dos Açores Angra do Heroismo, Azores Islands, May 27, 1940.

Was the mystery blown out of proportion by an investigator who wanted to make a name for himself at the time, thus opening the way for a lot of speculation in the future, as many suggest he did?

Or could it be the case that Briggs made a bad judgment about the state of his ship and, under harsh storm conditions, fearing for his family and his crew, left it all together in an attempt to reach land–but failed and drowned as a result. No one really knows for sure, and perhaps we never will. The case of the Mary Celeste is still a mystery unsolved.