For most people, the Arctic region of the North American continent is known for its harsh living conditions, extremely cold temperatures, and the remote vastness of the region. For scientists, however, this corner of the world is better known for giving them some headaches as they struggle with factual perplexities. Such as whether the modern-day Inuit are genetically the same people as the first arrivals.

The short answer is no, they are not. After one of the largest research efforts to answer the question, in which scientists examined the DNA remains of over 150 humans (samples from teeth, bones, hair) and compared the results with genomes of individuals living in relevant regions today (Alaska, Canada, Greenland, as well as Arctic Siberia), the picture is clear.

As LiveScience reports, earlier research had hinted that the people of the North American Arctic can be divided into two separate groups, the “Paleo-Eskimos” who first appeared some six millennia ago, and the “Neo-Eskimos,” who emerged nearly 4,000 years later. However, as the most recent research suggests, there is a genetic gap, no link whatsoever, between the first and the former.

The findings of the study, published in the journal Science on August 29, 2014, surprised scientists. Over 50 authors contributed to the paper, which concludes that the Paleo-Eskimo and Neo-Eskimo groups arrived at the North American Arctic in distinct migration events. Both would have likely commenced from Siberia in the far north of Asia, and traveled on the Bering Strait to reach the northernmost realms of the Americas. The earliest arrivals, six millennia ago, consequently formed the pre-Dorset and Saqqaq cultures, and later, around 800 BC, finally the Dorset culture.

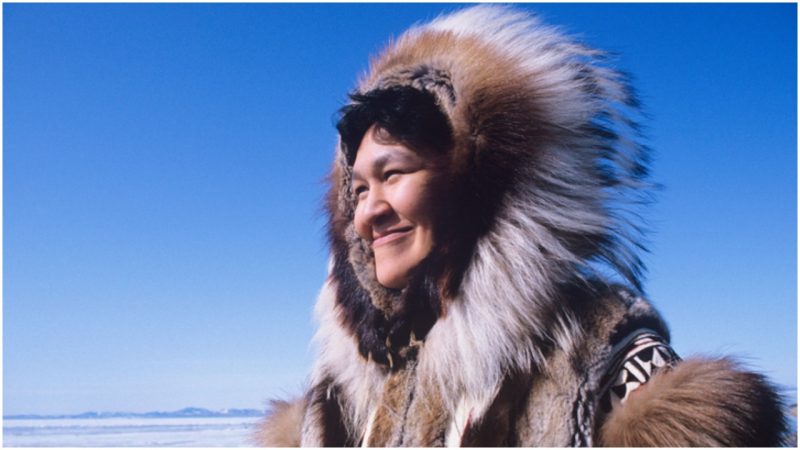

The Dorset culture reportedly came to an abrupt end under unclear circumstances some seven centuries ago. Around that time, the region saw the rise of the new Thule culture (Neo-Eskimos), which would have themselves arrived in a distinct wave of migration some 1,000 years ago. While the two groups lived in the same region for a certain period, it turns out they largely remained separate from one another. It was the Thule people who later gave way to the modern-day Inuit people, in the period between the 16th and the 19th century.

Scientists have reportedly identified some gene flow between the Paleo-Eskimos and the Neo-Eskimos but, as they clarify, it goes back to the ancient days in Siberia, to a common ancestor of the two distinct groups, before any of their separate migrations took their turn in history.

As for the Thule people, the actual ancestors of the Inuit, they followed a similar route to that of the Paleo-Eskimos on the Bering Strait. They also introduced new cultural goods in the Arctic such as dog sleds and new more elaborate weapons, Live Science writes.

The Dorset people and the groups from which they originated seem to have largely enjoyed solitude, thriving in isolation for ages. For one thing, all these older groups that inhabited the Arctic could have had a cultural mindset that did not allow them to easily adopt ideas from others.

The disappearance of the Dorset culture would not have lasted more than a century and a half (in between 1150 and 1350 AD), but just enough time for entire populations to vanish along with their culture and customs. Whether this was a peaceful event, or perhaps a violent one such as a genocide by the Thule, is something we can only speculate.

As the BBC reports, Inuit lore hints solely of the existence of friendly relationships between the Thule and those who preceded them in the Arctic. But even if there have been some sort of warring state between these peoples, the apparent lack of mingling, not to mention procreation, between individuals is still strange.

William Fitzhugh from the National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C., one of the study’s co-authors, has theorized on the matter. Members of the cultural units formed by the first arrivals may not have mingled with the Thule nor any of the ancestors of the modern Native Americans due to their “entirely different mindsets,” he remarks.

This would have meant that their customs, everything these people put their faith in, and even weaponry used, was different. In terms of their behavior, they had enjoyed solitude from other cultures, so would have been very cautious about introducing any “new ideas, new rituals, new materials and so forth” in their communities.

Some specific cultural traits are further known about each group after analysis of cultural artifacts. The earliest peoples from the first migration wave mostly relied on hunting reindeer and musk ox, while later groups, such as the Dorset culture, adopted different lifestyle and food choices; hunting more seals for instance.

According to Fitzhugh, it was the Thule people that “pioneered the hunting of large whales for the first time ever.” The Thule could have been the first in the world to have perfected whale-hunting skills. Concerning the modern-day Inuit, their traditional diet revolves more around walruses and seals.

Last but not least, the research not only reveals a clearer picture of how the Arctic was historically inhabited but also confirms that some Native Americans peoples are genetically distinct from the Paleo-Eskimos, unlike previously thought. According to Maanasa Raghavan, a molecular biologist from the National Museum of National History that is part of the University of Copenhagen, “the results of this paper have a bearing not just on the peopling of the Arctic, but also the peopling of the Americas.”

Related story from us: The fascinating diversity of the Inuit belief system

It was separate waves of migration that gave rise to the Thule people and their descendants the Inuit, but also to two other distinct groups of Native Americans further south, the experts conclude.