It would be lovely to be able to deliver a sweet and touching historical anecdote on the origin of Saint Valentine on St. Valentine’s Day. But there’s a wee difficulty with that. You don’t find hearts and flowers when you get to the beginning of the story of Valentine. You find martyrdom, imprisonment, plague, and death by clubbing. It’s hard to conceive of anything less romantic than death by clubbing.

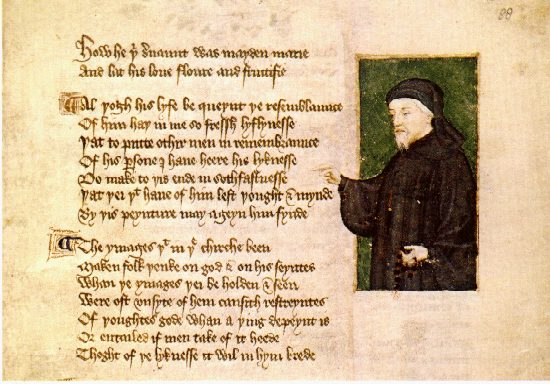

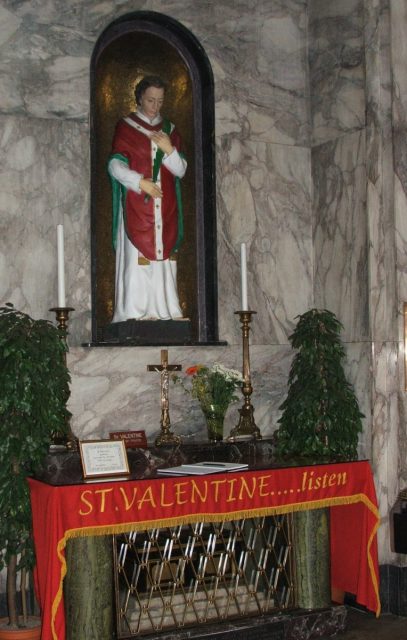

The Catholic Church distanced itself from St. Valentine’s Day a while ago, and not because of any sort of distaste for chocolate hearts or hand-holding. The evidence that there really was a person who committed acts worthy of sainthood is fragmentary. Valentine is one of the “saints whose cult is larger than themselves, so to speak,” according to Richard McBrien’s Lives of the Saints. In 1969, the Pope quietly dropped Valentine’s Day from the official calendar of saints’ days.

The consensus seems to be that Valentine is based on a Christian priest of that name who lived in Rome when the official religion was still pagan, during the reign of Claudius Gothicus, from 268 to 270 AD.

This was not a proud time in the history of the empire. Rome did not decline steadily from the glorious reigns of Julius and Augustus Ceasar to the crumbling under Honorius in 423 AD. There were peaks and valleys. This was a valley. Emperors rapidly succeeded each other through assassination in the mid-Third Century. There was death by poison, death by strangulation, death by hanging, death by being dragged naked from the back of a chariot through the streets. The year 238 AD saw six different emperors.

Claudius Gothicus, the Ceasar who would, legend has it, confront Valentine, was born a peasant in what is now Serbia and rose rapidly through the ranks of the army. He was popular with the soldiers, a very tall man who liked to fight. His specialty was punching so hard it knocked out the teeth of an opponent, including, once, an opponent’s horse. As the story goes, he could knock out man–or horse–with a single punch.

Claudius Gothicus played a key role in the assassination plot that eliminated Emperor Gallenius in Milan. That is very how much how it worked in the Third Century.

But the Rome that Claudius took charge of was near-bankrupt, with rebel populations causing lots of trouble in German and France in the West, and Syria in the East. Claudius desperately needed more soldiers in the Army, and he tried to officially discourage men from marrying.

As the story goes, Claudius heard that the priest Valentine was busy marrying young Christian couples. Marriage was frowned on; Christianity forbidden. Valentine was arrested, unsurprisingly. Pressure was put on the priest to abandon his faith; he refused.

The emperor decided to visit Valentine in prison. During this meeting, instead of being meek and obliging, Valentine tried to convert Claudius to Christianity. Disgusted, the emperor ordered his execution. Valentine was clubbed to death and then beheaded.

Three centuries later, long after Emperor Claudius the horse puncher had died of the plague, a pope declared February 14th Valentine’s day. One theory is that the Catholic leaders really wanted to banish the mid-February fertility celebration of Lupercalia. (What happened during Lupercalia? Let your imagination run wild and you still haven’t come close.) Naming the day in honor of the martyred Valentine seems a bit random today. Nonetheless, the new holiday stuck, and in medieval times, all sorts of romantic stories were told.

Did any of these sweet tales have anything to do with the Third Century Valentine? Only one, that the night before the rebellious priest was to be executed, he wrote a letter to the daughter of his jailer, and signed it “Your Valentine.

The first Valentine’s Day card was born.