When Hiram Bingham first laid eyes on Machu Picchu he had no idea the enormity of what he was seeing. Machu Picchu is an Inca citadel built in the 15th century. Known worldwide, the citadel was reportedly built as a home for the Emperor Pachacuti, and was abandoned by the Incas a century later when the Spanish conquest began. Located high in the Andes Mountains in Peru, it was built in the classical Inca style, with polished stone walls.

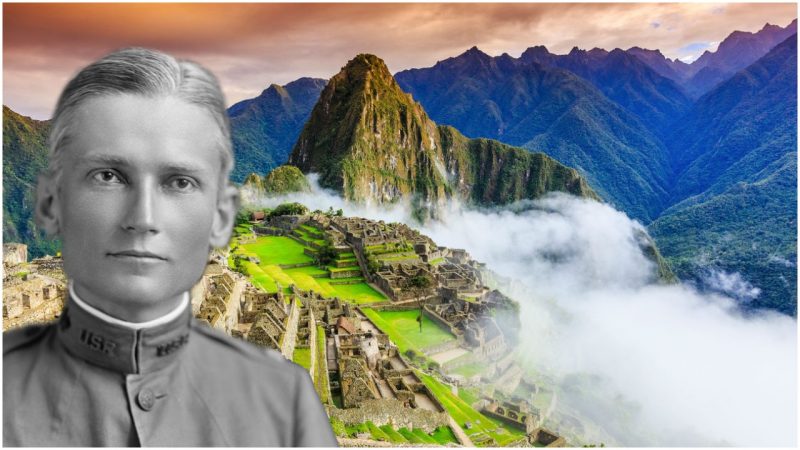

This UNESCO World Heritage Site was always known by the local population and became known to the Spaniards during their colonial period. However, it only became known to the world after Hiram Bingham, an American academic, explorer, and politician, introduced Machu Picchu to Western civilization. The award for the discovery of this marvelous creation went to Hiram Bingham, although of course, he didn’t discover anything.

Machu Picchu was always known to the locals, and later the Spanish. In 1909, the American historian and lecturer at Yale University was returning from the Pan-American Scientific Congress held in Santiago. As he had to travel through Peru, he got an invitation to visit and explore the Inca ruins at Choqquequirau in the Apurimac Valley, and this is what triggered his interest in the remains of Inca culture.

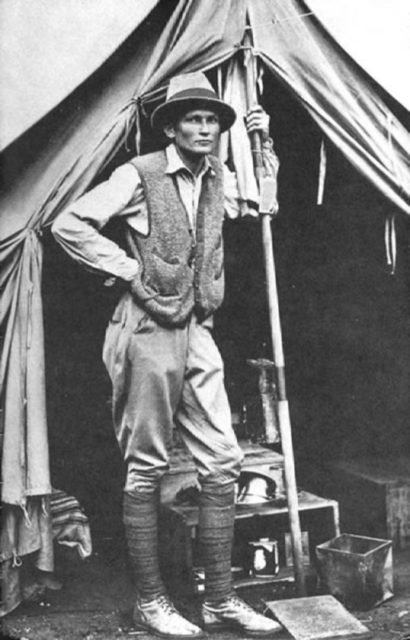

Although he was not a trained archaeologist, in 1911 he organized the Yale-Peruvian expedition, with the ultimate goal of discovering the lost Inca capital, Vitcos. Bingham armed himself with some knowledge by consulting with Carlos Romero, a historian who lived in Lima, and so the expedition began.

Traveling down the Urubamba river, he gathered various information from the local population. After the examination of several Inca ruins and realizing they still hadn’t found Vitcos, the expedition set up a camp at Mandor Pampa. Here, Bingham met and questioned Melchor Arteaga, a local farmer, and innkeeper, if he had some information about Inca remains in the area. Receiving an affirmative answer, Arteaga took Bingham across the river and up the Huayna Picchu mountain.

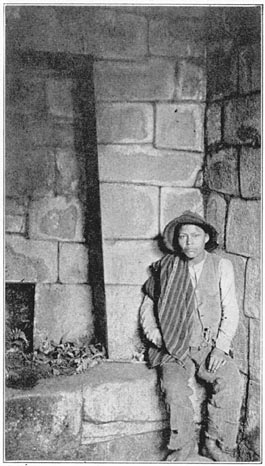

On the very top of the mountain, they met a couple living there. This couple was actually farming the agricultural terraces of Machu Picchu and had cleared the area four years earlier. The first walk of the explorer among the ruins was led by the couple’s 11-year-old son, Pablito. The child already knew the site very well and was Bingham’s first guide around Machu Picchu.

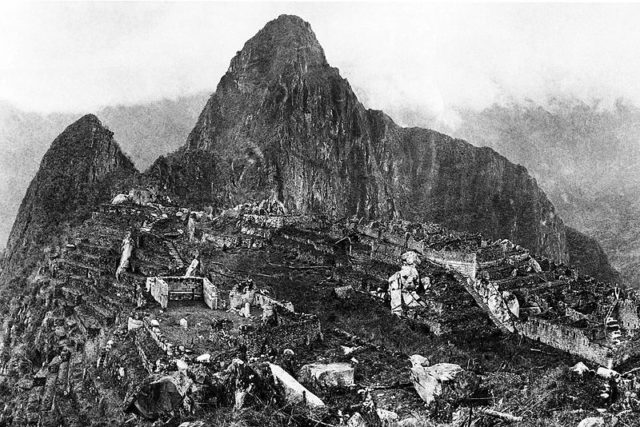

As Bingham walked among the ruins of Machu Picchu, he noted that the remains of the buildings were mostly covered in rich vegetation, and he was, therefore, unable to get the full extent of the archaeological site. After documenting and photographing the remains, Bingham left Machu Picchu, certain that he hadn’t found the city of Vitcos.

The expedition continued down the Urubamba River and up the Vilcabamba River, examining all the ruins they could find along the way. Led by locals, Bingham finally managed to locate and identify the city of Vitcos, known as Rosaspata at the time.

He also discovered the temple of Chuquipalta, and left for the Pampaconas valley, only to find more ruins, heavily overgrown by jungle vegetation. Not researching the site thoroughly, he only noted a few of the buildings, and he named the site Eromboni Pampa. (Later, in 1964, Gene Savoy, an American explorer, fully researched the site and managed to identify it as Vilcabamba Viejo, the city where the Incas ran from the Spanish after the abandonment of Vitcos.)

On his way back, Bingham sent two members of his team to clean and map Machu Picchu. Having failed to identify Vilcabamba Viejo before, he was certain that Machu Picchu was actually Vilcabamba Viejo. He didn’t realize the differences between the two sites: Machu Picchu was built at the height of the Incan empire and showed spectacular craftsmanship, and Vilcabamba Viejo was built quickly, in the Neo-Incan style.

In 1912, Bingham got a sponsorship from Yale University and the National Geographic Society, so he went back to Machu Picchu. This time they did a massive four-month clearing of the site, with the help of the local population. The excavation started in the same year, and it continued through to 1915. Impressed by the fine stonework and the well-preserved ruins, Bingham focused on finding the correct story behind the existence of Machu Picchu, but, as further research has been done, all of his many theories have since been proven to be wrong.

During his research, Bingham collected a huge amount of Incan artifacts which he took to Yale. At first, the local institutions welcomed the explorers and were happy that the knowledge of their ancestors was increasing. However, they later accused Bingham and his team of stealing artifacts and smuggling them out of Peru.

The accusations were supported by the local press, and they claimed that Bingham and his expedition had harmed the archaeological site and that the local archaeologists were robbed of the knowledge of their own history. The locals began to defend their ownership of Machu Picchu, as Bingham claimed that the artifacts were taken to Yale to be studied by American experts, openly and legally.

After his return home, Hiram Bingham exulted in his discovery of Macchu Picchu. But, as discovered by his letters later, a lot of his statements were proven to be wrong. He claimed that he searched for this site for a long period of time, although he found it on a 48-hour journey when finding Machu Picchu was not even the main goal of this trip.

He claimed that the paths to Machu Picchu were inaccessible, but his letters show that he used a modern road system and traveled with ease. Another false statement of Bingham’s was that Machu Picchu was covered in dense vegetation, although his son later published photographs that show some of the ruins in a clear, open space. The same letters and photographs suggested that Machu Picchu was not isolated in a wilderness, but well connected and even populated by several families.

Bingham’s own son, Alfred, claims that at first his father did not value his findings at Machu Picchu, as it was not his primary goal, and he spent only one afternoon there. Later, some plantation owners told Bingham that very little was known about the location’s existence and history.

Read another story from us: Ciudad Perdida: The “Lost City” of Colombia

Bingham’s lasting contribution lies in his presentation of Machu Picchu to the world and the undertaking of a rigorous study of the site, and not in its discovery.