It’s September in 1944. Following their successful landing on the coast of Normandy in June, the U.S. Army has set up camp next to Saint-Valery-en-Caux and Saint-Valery-sur-Somme, two neighboring and rather cute little northern villages right next to the port of Le Havre in France.

They were once homes and cozy retreats for the likes of Jules Verne, Victor Hugo, and Degas. On this historic September day, the settlements are in full service to Camp Lucky Strike, and the soldiers are there are not to write fiction but history. Yet, for the time being, they are stuck here until further notice, in one of the many Cigarettes Camps formed by the Americans in those few miles between Le Havre and Ruen.

But not for long. Operation Astonia and the battle for Hitler’s Festung Le Havre and the English Channel is about to get underway.

It’s going to allow for faster supplies of food and a safer way to import fresh soldiers and make the final push against the retreating Nazis in France. Or if not that, then at least to extract the injured, the worn out. The ones who already gave their best and couldn’t give anything to the cause anymore.

And it did. Almost three million American soldiers passed the Channel and either entered or left the continent through Le Havre, the “Gateway to America,” as it came to be known back then. Those who left their homes in the United States between 1944 and 1946 in order to fight the battle for Normandy, the northern coast of France, and the total annihilation of the harbor in Le Havre that followed, were shipped from the East Coast harbors across the Atlantic to France. After landing on the northern coast, they were immediately ferried to these camps named after America’s homemade cigarette brands. Strange names perhaps, but still many times better than naming them Camp Saint-Valery and reveal the location to the enemy.

More than 20 staging camps, within a month or so, were erected in the nearby forest and the fields next to the city, in what the Army labeled the “Red Horse” staging area. Philip Morris, Lucky Strike, Pall Mall, and Camp Old Gold, among others–and the thousands and thousands of tents and wooden huts within–housed every American soldier right before he was sent to the front and into battle, or as a reception station for those who came back and were about to leave.

Camp Lucky Strike was a necessary port of entry for almost every single one. It nursed, lodged, trained, and fed no less than 100,000 persons each and every day, and gave a pass to almost two million soldiers. It was probably the most important military camp in Europe, where all shivered at the thought of not knowing what tomorrow will bring and shuddered over the horrors of the yesterdays, as they were waiting, wounded and maddened by the war, to go home at last.

While many movies focused on what went on in the days of battle, almost none, well except for William Wellman’s Battleground from 1949, tried to showcase life in between those days. Not just inside the tents of these camps and the military barracks, but as a whole, how they spent the evenings, the mornings, and the afternoons. What did they eat? And how, when, and who fed them? Did they bathe the blood of their fellow privates with their clothes? Did they sleep?

These were the lives of every single one of them then and there, which sadly for more than a few ended too soon after the Battle of the Bulge. The last major German attack near the end of the war caught the Allied forces by surprise and made sure many individual stories were untold. And while some former members of the 488th Engineers Company spoke about their day to day life in the camp, saying, “the heat from the stoves barely heated the tents and seemed only effective at thawing the frozen dirt floors so by morning the cots had settled into a good four inches of mud,” or that “under the floor of the tents the rats grew to cat size and sounded as though they were wearing boots when they tramped around while the men were trying to sleep at night,” many did not live to tell their tale and what they witnessed was forever lost with them in that exact moment when they lost their lives.

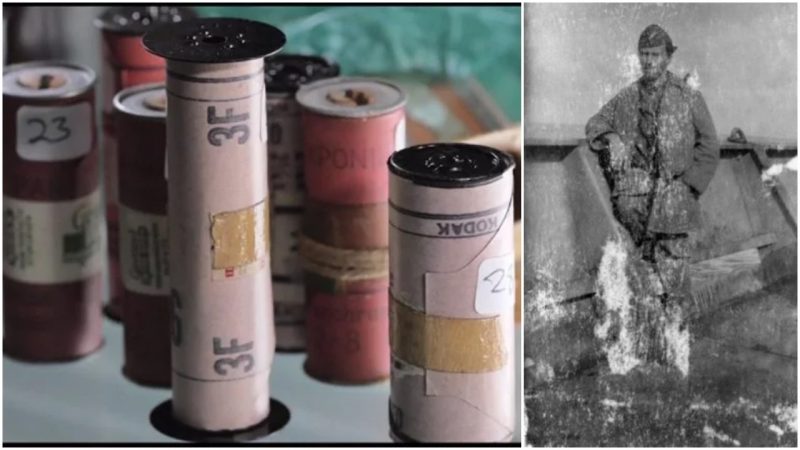

That changed when someone’s long-lost recollection of those days was found in the form of a film roll, tucked away in a far corner that no one visited for decades, and shows moments that were believed to be lost forever.“When I pull the film that I just developed out of my film developing tank and look at them, I’m the very first person who’s ever seen that picture. They’ve never been enjoyed, they’ve never been remembered,” says Levi Bettweiser, a photographer and the founder of the Rescued Film Project, who was the one who developed, and the first to see, what one unknown solder saw through his camera lens almost 80 years ago.

Through this project, Bettweiser aims to recover lost, unclaimed, and undeveloped film rolls and compose a gallery of online images that were captured in some space in time between the 1930s and the late 1990s in an attempt to reveal life from the past couple of decades and all through the special memories of individuals that captured but didn’t have the chance to share their significant moments.

They develop damaged and degraded film rolls, recovered from places all over the world, and their biggest find was in 2014 when, at an auction in Ohio, Bettweiser stumbled across 31 undeveloped film rolls shot by an unknown soldier during World War II.

“I perceive all the images that I rescue as historical. It doesn’t matter if the shot was shot in the 1990s, I see that as being a piece of history. But this batch of film automatically has the weight of potentially having extreme historical value,” explains the photographer as he was getting ready to carefully develop the films, which were severely damaged and degraded by heat and moisture through the years, by hand in his kitchen.

They are all labeled with location names such as Boston Harbor, Start of Train Trip, Roll of French Funeral, Lucky Strike Beach, and LaHavre Harbor, and after being successfully developed, these 70-years-old film rolls revealed some of those missing and rarely mentioned moments of a soldier’s everyday life during the war days.

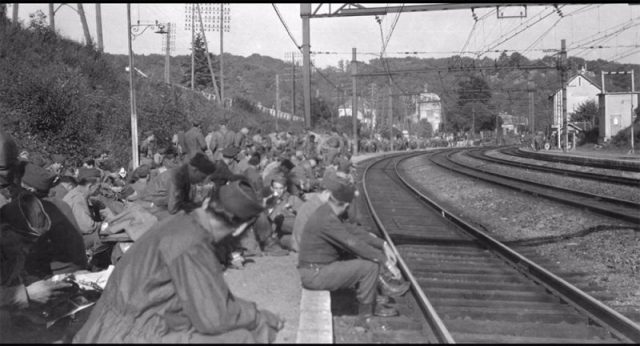

They include wide shots of the military camps, tents, and one of the main streets in Camp Lucky Strike with the wooden barracks placed aside. Group shots of soldiers waiting in a line, probably for food or a bath. An image showing hundreds of them exiting a church, and a few group shots of thousands waiting for a train to arrive as they were heading for their next, and for some sadly the last, designated stop. A birds-eye view and up close and personal shots of someone’s memorial. Image showing boats with Uncle Sam “Welcome Home” and “Well Done” signs on them.

They are ordinary but wonderful flashes of history that suck in the viewers, transporting them in that fraction of time when they were shot, letting every single one taste the personal importance of the one who took them. Just as much as they can feel the historical weight forever captured in the pictures. Imagine opening one that was rolled in a Red Cross letter, beginning with: “I’ve always had a loathsome life, dreaming of success and love…”

“Every image in The Rescued Film Project at some point, was special for someone. Each frame captured reflects a moment that was intended to be remembered. The picture was taken, the roll was finished, wound up, and for reasons, we can only speculate, was never developed. These moments never made it into photo albums or framed neatly on walls. We believe that these images deserve to be seen so that the photographer’s personal experiences can be shared. Forever marking their existence in history.” (The Rescue Film Project, on the question of “Why do We Rescue film?“)

Here is another story from us: From Fireside Chats to ‘War of the Worlds,’ the early days of radio

As for who was the man who shot this pictures and never made to frame them, it is still unclear. What is, is that he made the trip across the Atlantic from Boston to Le Havre and Camp Lucky strike, but not the trip back. At least not with what he captured.