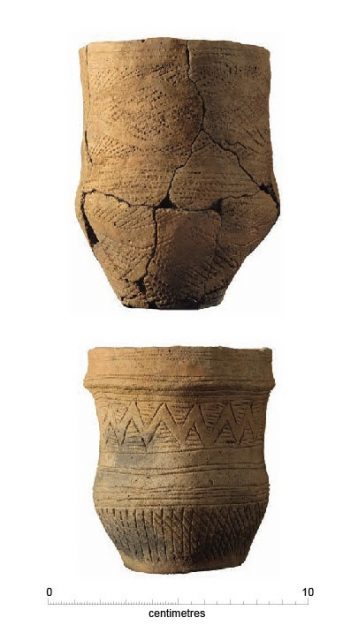

For long time archaeologists have come across graveyards where people were buried with Beaker pottery, recognizable for its bell shape, fine texture, and thin walls. This pottery was used probably as drinking containers and started to appear in different parts of Europe some 4,700 years ago. It ceased to be used several centuries later.

The Beaker pottery, however, was more than just something to drink from. Rather it was an entire phenomenon with other artifacts associated with the Beaker culture and people, whose origins and ancestry are linked to territories of central Europe as well as further east to the Steppes. For many decades, archaeologists have had a hard time in establishing the narrative of everything Beaker. Since there are so many burial pits from the era containing this type of artifact, they could only theorize that the pottery must have had significant value for the owners buried with it.

Particular questions have been raised how the Beaker pottery was introduced in prehistoric times in different areas of Europe. Was it a process of cultural diffusion, where the idea to produce such pottery simply traveled from one group of peoples to another, without significant population movements? Or was it mass migration that introduced the Beaker pottery to new territories? The latest scientific research has finally provided some answers to these questions, and according to it, both explanations of how the pottery spread are correct.

The research findings say that in continental Europe, migration did not play a pivotal role in how this pottery was spread. Perhaps much more significantly, however, scientists have managed to document that it was migration that brought Beaker pottery to Britain, and with it, a wave of migrants that replaced the population on the island in dramatic numbers. The in-depth study that has been carried out scrutinized ancient DNA genomes, including those of human remains associated with the Beaker culture. A truly international team of 144 archaeologists and geneticists, all coming from top-notch institutions from Europe and the United States, had input.

The genomes analyzed have been retrieved from 400 European individuals, dated to three periods: the Neolithic, the Copper Age, and the Bronze Age, of whom 226 are associated with the Beaker culture. Novel methods for DNA analysis have largely helped the research effort. One of these employs a specific chemical treatment that enables researchers in ancient DNA laboratories to pay attention to the most resourceful bits of the genomes subjected to analysis. Another has to do with taking advantage of DNA from petrous bones, as this particular piece of the human skeleton has reportedly provided some of the most significant data.

As researchers write, there is loose genetic matching between remains of humans related with the Beaker culture from the Iberian peninsula and from central parts of Europe, which excludes the option that migration was a key-player in how the pottery traveled between these distinct areas of the European continent. Still, migration seems to have been unquestionably the factor for the subsequent distribution of Beaker artifacts, and this part of the research findings most concern Britain.

The introduction of Beaker pottery on the island also meant an influx of new population, one which reportedly replaced astonishing 90 percent of Britain’s gene pool in a period of just a few centuries. The findings have been published in the journal Nature on February 21, 2018.

Given the scale of the study, it is comparable to genome studies done on modern-day humans; the results illustrate that pottery does not necessarily go “hand-in-hand with people.”

In the words of co-senior study author Ian Armit, an archaeologist from the University of Bradford in the U.K., quoted in the Cambridge Archaeology study, “the pot versus people debate has been one of the most important and long-running questions in archaeology.”

“DNA from skeletons associated with Beaker burials in Iberia was not close to that in central European skeletons,” said the first author of the study, Iñigo Olalde, a geneticist at Boston’s Harvard Medical School. That means that scientists are positive that migration did not play a pivotal role in spreading Beaker pottery across continental Europe. However, it did help the pottery to reach other regions, such as Britain.

Geneticist Wolfgang Haak from the German-based Max Planck Institute has pointed to previous research as of 2015, which has shown that around 4,500 years ago, “there was a minimum 70 percent replacement of the population of north-central Europe by massive migrations of groups from the eastern European steppe.” According to the study, something similar happened as this same wave of migrations proceeded later to Britain. The Beaker artifacts certainly traveled with the newcomers.

For the Britain part of the story, analysis of DNA samples reveals that the human remains dated from six to three millennia ago are different from those of the people who inhabited the island immediately after this period. “At least 90 percent of the ancestry of Britons was replaced by a group from the continent,” said geneticist Ian Barnes at London’s Natural History Museum and another of the co-authors. “Following the Beaker spread, there was a population in Britain that for the first time had ancestry and skin and eye pigmentation similar to the majority of Britons today,” he said.

The new population would have arrived in Britain shortly after Stonehenge was completed, and given the magnitude of population replacement, the events must have been disruptive.

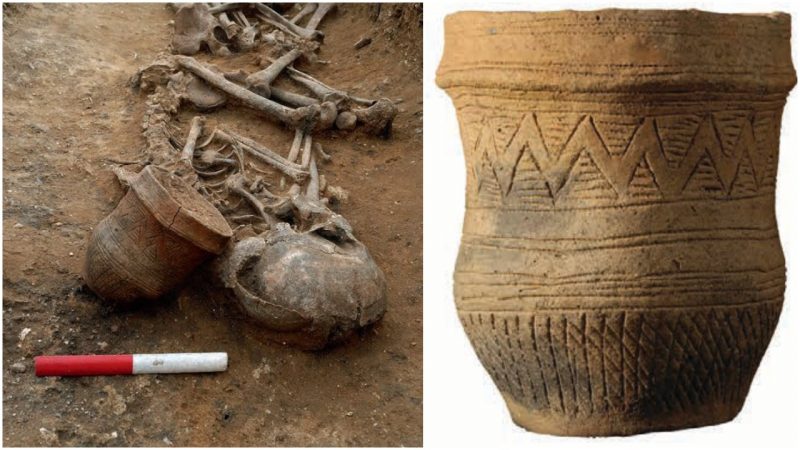

Two of the ancient DNA samples analyzed that originated in Britain were of a double Beaker-associated grave unearthed at Trumpington Meadows, near Cambridge. The Beaker-associated burial pit from this location included one female aged between 16 and 18, and a male aged between 17 and 20. They would have been buried here around 2000 B.C.. Typically for the period, both skeletons were found with fine-ware beakers, and analysis has confirmed that the pair were once relatives and they had a continental lineage.

The Executive Director for the Cambridge Archaeological Unit, Christopher Evans, who also appears as one of the co-authors of the study, said “the results are truly ground-breaking and suggest that, with the influx of Continental communities, Britain’s prehistoric story needs to be rewritten in a much more dynamic manner.” He also says that further analysis in the forthcoming years will reveal more details at how populations changed on the island in prehistoric days.

“There can be no doubt of how our long-established picture of Britain’s past is now changing,” Evans said.