To open Pandora’s box is a widely used metaphor that means to do something that may seem innocent but can have severe, if not catastrophic, consequences. While the phrase itself is well-known, there is a problem: the box itself that Pandora opens. The box, which contained all the evils of the world, all the sorrows, wrath, or contempt, was, until the 16th century, not a box–it was a jar.

To explain this, we need to get to the root of the story, which unsurprisingly brings us to the ancient Greeks and their inexhaustible mythological world, in which Pandora was the first mortal woman on Earth. A significant figure, she is also the mother of the first mortal child.

Pandora’s daughter, Pyrrha (Fire), along with her husband, Deucalion, were the sole survivors in the Great Deluge myth. This flood was sent by Zeus to punish mankind for their terrible behavior that, perversely, was caused by the evils in Pandora’s box being unleashed.

We know Pandora’s story thanks to Hesiod and the epic poems he wrote around the 7th century B.C. They reveal how and why Pandora was created in the first place and how “a gift” that Zeus presented to her eventually concluded an era of humankind in which there were no worries, no diseases, and people lived eternal lives.

According to the narratives, Pandora comes as a sort of punishment to humanity following another mythological episode in which Prometheus steals fire from the Gods and gifts it to humankind. After such a treacherous act from Prometheus, Zeus instructs other deities to mold a woman from the earth, and that is how Pandora arrived in the world. An alluring figure, Athena made a glowing dress to cover her body, and Hephaestus adorned her head with a diadem. She also received unique character qualities.

The first bride of the world, her name means “all gifts,” and once her creation was complete, Zeus sent her to Epimetheus, who was the brother of Prometheus. Though warned by his brother to never welcome anything from Zeus, Epimetheus did let Pandora into his household.

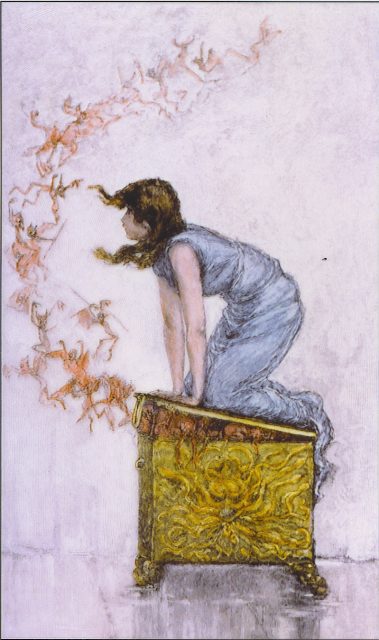

She arrived at his house, and brought with her a jar, a wedding gift from Zeus that he had instructed her never to open. But, in her unquenchable curiosity to find out what was in the jar, Pandora opened it and inadvertently released all the troubles ever known to humankind, such as diseases, strife, and despair, which is how the Golden Age of Men came to an end. As the story concludes, only one thing remained inside the jar, which was Elpis–the spirit of hope.

In Hesiod’s recollection of the myth, the exact word that was used for the ill-fated jar is “pithos,” which were huge jars used for storage among the ancient Greeks and commonly buried in the ground. Storytellers of the Pandora myth remained faithful to the wording for at least two millennia, but in the 16th century A.D., translators of the story made an error while translating the word pithos and the mistake stuck.

As sources suggest, this person was 16th-century humanist Erasmus of Rotterdam. While translating Hesiod’s tale of Pandora into Latin, he reportedly translated “pithos,” meaning jar, into “pyxis,” a Latin word for box or casket. Another name that is suggested as making a similar mistake while translating the story in 1580 is that of Italian scholar Lilius Giraldus of Ferrara.

The interpretation of the story’s pivotal element was further established by the 19th-century painting of Pandora by Dante Gabriel Rossetti, who dramatically presented her holding a box that would unleash all the evils of the world. The fate of the wording was sealed. Luckily, the story still ended with Elpis remaining at the bottom of the pithos, the jar, the box, or the casket, however you please, the only blessing which soothed mankind’s suffering.

The error eventually came to the attention of critics and scholars. In the beginning of the 20th century, British linguist and scholar Jane Ellen Harrison contemplated the gravity of the mistranslation. She would even dub the Pandora myth as “completely misunderstood,” and for good reasons too.

According to Harrison’s writings on the topic, such a mistranslation clearly weakened the myth of Pandora from its genuine context in the ancient Greek customs, or its connectedness with the festival of Anthesteria that was held each spring and lasted up to three days.

The first day of this festival was known as Pithogia and it was when the casks of wine sealed the previous year were opened in hopes that by the springtime the wine had matured. However, people also believed that with opening the wine jars, the souls from the underworld were also released. On the following day, the men performed a number of customs such as chewing blackthorn to protect themselves from the freed souls of their dearly departed.

Harrison’s arguments were backed by claims that Pandora was an early human representation of Gaia, or the Earth itself. In this context, the pithos connect her figure to the Earth and using the words such as box and casket are only set to down-scale Pandora’s cultural significance as a figure. Such a representation of Pandora can be spotted in ancient Greek vase paintings in which she is either a statue-like figure surrounded by other deities or a woman emerging from the earth.