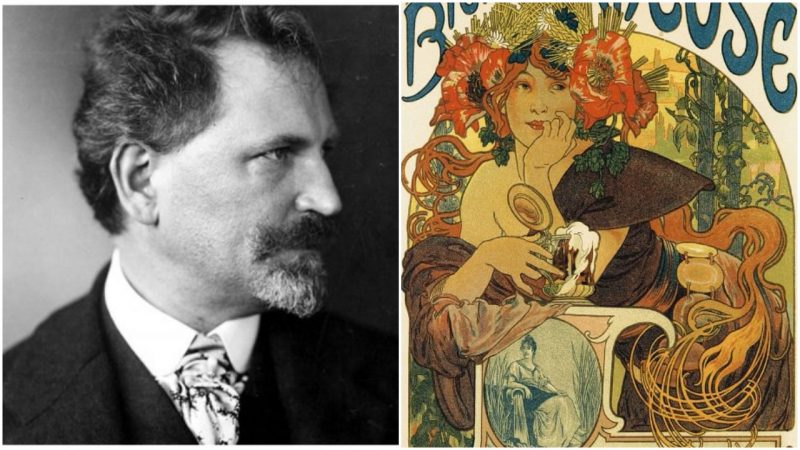

The beginning of the 20th century was marked by an extraordinary art movement known as Art Nouveau. Its main objective was to modernize design, escaping from the previously popular eclectic historical styles. One of the artists closely linked to this art movement is Alfons Mucha, born in Moravia in 1860.

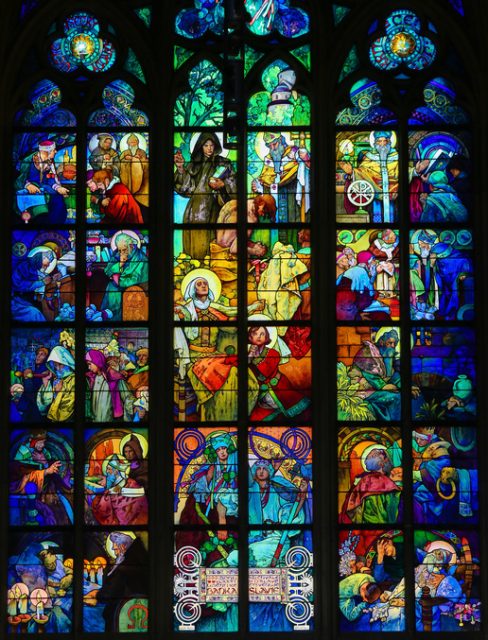

Owing to Mucha, the Prague we see today is overwhelmed by Art Nouveau splendor and artistry, reflected in not only building facades and museums but also shops that offer Art Nouveau-inspired products such as lamps, jewelry, and chocolate boxes.

After being rejected by the Prague Academy of Fine Arts, Mucha, aged 19, went to Vienna to work as a theatrical set painter. In 1887 he moved to Paris, where he studied at the Julian Academy, but his money ran out and he started looking for a job as an illustrator. Struggling to make a living, Mucha finally attracted the public’s eye in 1894, when he was commissioned to produce a poster for the actress Sarah Bernhardt. The poster thrilled Sarah and captivated her audience enough for “le style Mucha” to be born.

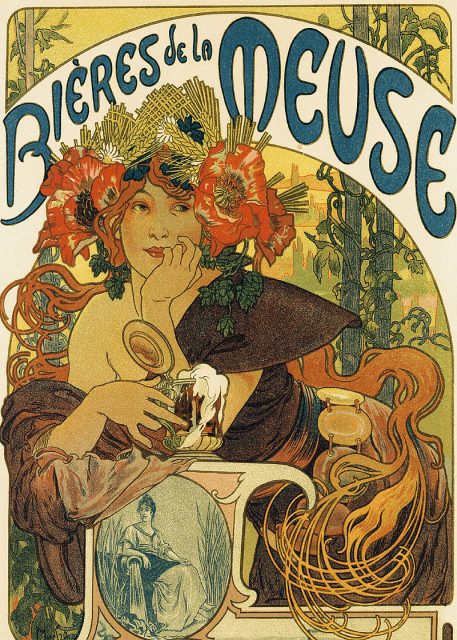

Mucha’s career in the years to come was a list of one triumph after another. He designed stage decorations, furniture, posters, and even collaborated with the Lumiere Brothers. The public fancied his unique style, so it didn’t take long for it to become commercially used on liquor and perfume bottles, chocolate wrappers, and decorative panels.

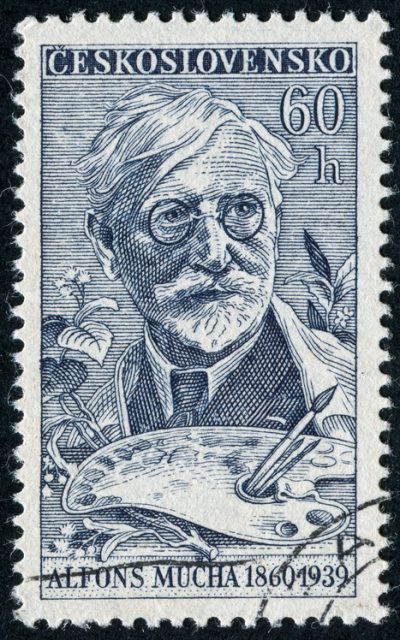

Mucha was an important artist to the entire nation. When the Republic of Czechoslovakia was formed in 1918, he designed the first stamp. Mucha’s most praised achievement was his “Slav Epic,” a series of 20 large-format paintings that represented the lives of Slavic people through a depiction of different events, summarizing the Slavonic history. He painted the Slav Epic between 1912 and 1926 in the studio at Zbiroh Chateau.

During the Nazi occupation, these works were wrapped up and hidden away to prevent them from being captured by the Gestapo, who were much interested in Mucha. The Nazis were unlikely to be appreciative of an epic devoted to Slavs because one of the cornerstone of Hitler’s ideology was his belief that Slavs were subhuman. Mucha’s work escaped their grasp but he did fall into the hands of the Gestapo. Over time, the Nazi interest in Mucha has raised many questions and seems tied up in Mucha’s involvement in the secret community of Czech Masons.

The year 1939 marked the beginning of one of the darkest periods in Czech history. The territory of Bohemia and Moravia was occupied by Hitler’s Germany. The Nazis intended to destroy all the Slavic and Jewish communities. Mucha was one of the first artists arrested by the Gestapo.

According to the Diary of the Winners project, the Nazis had information about his membership in the secretive Czech Masonic movement. He is believed to have joined a Masons lodge in Paris at the turn of the century. From 1922 till 1938 Mucha exerted considerable influence in the circle in Czechoslovakia. It is said that he was called the Grand Commander. Even his residence, the historic Zbiroh Chateau, is regarded as a meeting place for the grandmasters.

The Nazis deeply hated the Freemasons. In Mein Kampf, Hitler ranted about their subversive power, and blamed the Masons for being a cause of Germany losing World War I.

The Gestapo’s focus on the artist’s Masonic activities was prompted by a collaborator, Jirzhi Arved Smichkovsky, who was present at Mucha’s interrogation. Smichkovsky was a scholar and an expert in law, philosophy, and theology, fluently speaking German, Italian, Latin, Classical Greek, and Hebrew.

Unofficially, Smichkovsky was interested in occultism and black magic. Since the beginning of the occupation, he collaborated with the Sicherheitsdienst, a German secret service, becoming one of its most dangerous agents. His extensive knowledge and shrewdness brought much to the attention of Nazi occupants.

The Gestapo’s harsh interrogations severely damaged Mucha’s physical and mental health. Soon after, he was diagnosed with pneumonia and released due to his frail condition. The illness and the wartime sufferings took their toll, and on July 14, 1939, Alfons Mucha died, at the age of 79. He was buried at the Vysherad Cemetery in Prague, on the site of national pride.

There were around 100,000 attendees at Mucha’s funeral despite the Nazi ban. Mucha’s fellow supporters of anti-fascism gave a mourning speech, which embodied the Czech resistance to fascist ideology.