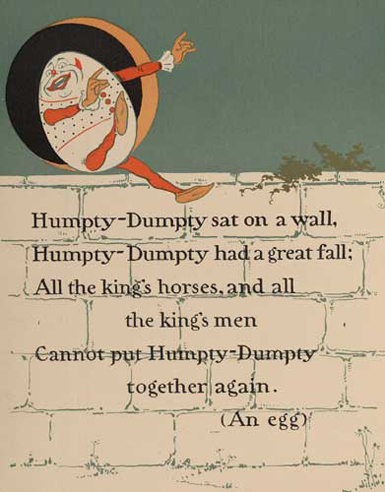

Humpty Dumpty sat on a wall. The words are an indelible part of nearly every English speaker’s childhood. Humpty Dumpty had a great fall. You probably know the nursery rhyme so well you don’t give it a second thought. All the king’s horses and all the king’s men… You may have forgotten that the rhythmic recitation was originally a riddle. … couldn’t put Humpty together again.

But while the solution to the nonsensical nursery rhyme is so well known that Humpty Dumpty’s egg shape has become synonymous with his identity, the question remains, Where did the rhyme come from, and what did it originally mean? Popular theories abound, though they’re probably more fanciful than factual.

Some say Humpty Dumpty is a sly allusion to King Richard III, whose brutal 26-month reign ended with his death in the Battle of Bosworth in 1485. In this speculative version, King Richard III’s horse was supposedly called “Wall,” off of which he fell during battle. He was bludgeoned so severely his men could not save him, becoming the last king to die in battle.

Historians long thought King Richard III was humpbacked. Shakespeare perpetuated this myth, famously portraying him as “a poisonous bump-backed toad” in his historical play, which was first performed in the early 1600s.

The 2012 discovery of Richard III’s skeleton beneath a parking lot in Leicester led to an updated diagnosis of severe scoliosis, which meant one shoulder might have been a little higher. The skeletal remains also showed evidence of 11 wounds, eight of which were to the skull.

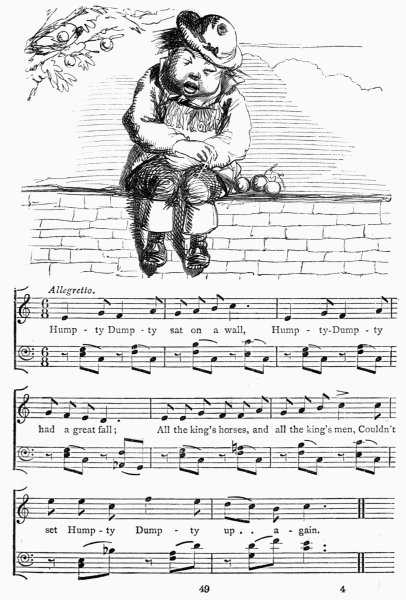

The Humpty Dumpty rhyme first appeared in print in Samuel Arnold’s Juvenile Amusement, published in 1797, though the third line was slightly different—“Four-score men and four-score more.”

A more recently popular theory attaches Humpty Dumpty to a cannon in Colchester, England, during the town’s siege in 1648. The town had a majestic castle and several churches encircled by a protective wall. A large and heavy cannon, nicknamed Humpty Dumpty, was strategically placed atop St Mary’s as the Wall Church to defend the city, and manned by “One-Eyed” Jack Thompson. The top of the church tower was hit by the enemy, causing the cannon to tumble to the ground, where it shattered and could not be put back together again.

This theory gained traction in the 1990s with the publication of a book about nursery-rhyme origins, but the Oxford Dictionary of Nursery Rhymes points out that the cannon story originated in a spoof published by Oxford Magazine in 1956.

Humpty Dumpty may also have been a drink of brandy boiled with ale. Though that sounds unappetizing, some modern mixologists have resurrected the cocktail.

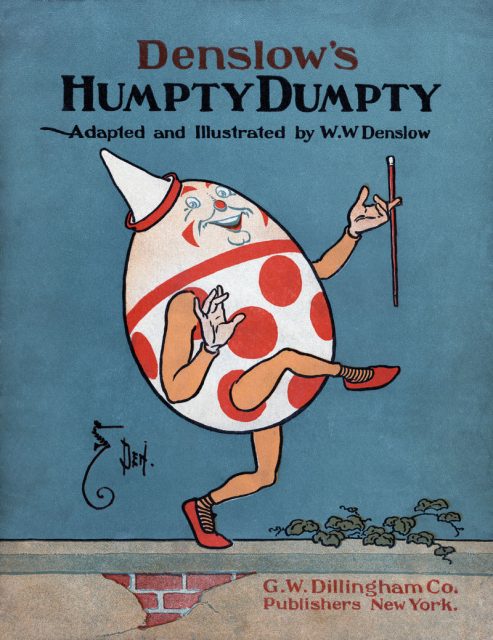

In Mother Goose’s Melody, published in 1803, the last line was “couldn’t set Humpty up again,” and he was portrayed not as an egg but as a fat boy.

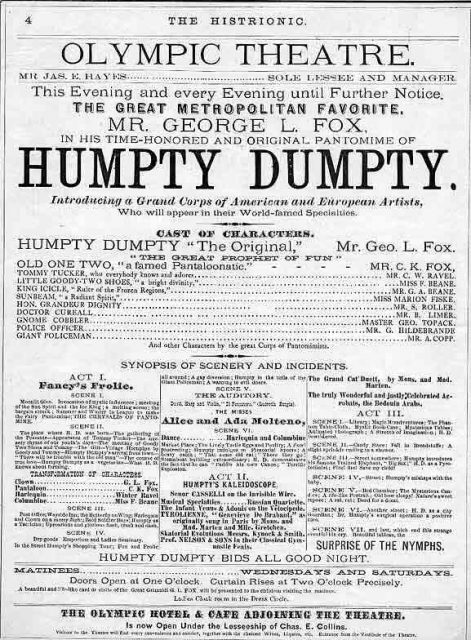

Over the years, references to Humpty Dumpty have turned up in all kinds of artistic interpretations. Songs include “I’m Sitting on Top of the World,” written in 1925 and Travis’s “The Humpty Dumpty Love Song,” in 2001. Literary allusions include, among many others, All the King’s Men, by Robert Penn Warren, and All the President’s Men, by Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein.

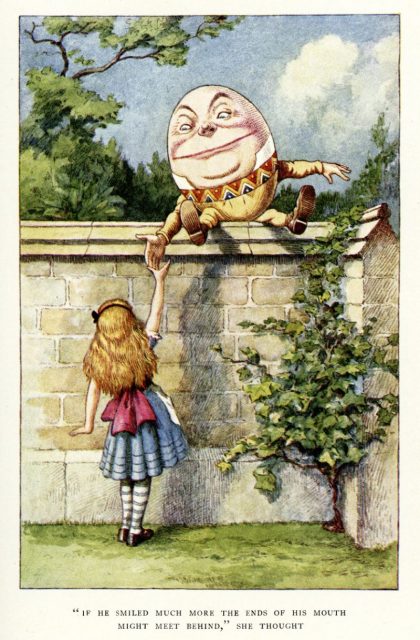

But Humpty Dumpty’s most famous literary appearance is certainly in Lewis Carroll’s Through the Looking-Glass (1872), in which he appears as a fussily exacting egg-head who corrects Alice’s grammar and discusses the value and meaning of words.

“When I use a word,” Humpty Dumpty said [to Alice], in rather a scornful tone, “it means just what I choose it to mean—neither more nor less.”

The classic Carroll illogical logic has actually been cited by attorneys in both U.K. and U.S. courts. Humpty Dumpty goes on to scold Alice: “They’ve a temper, some of them—particularly verbs, they’re the proudest—adjectives you can do anything with, but not verbs—however, I can manage the whole lot! Impenetrability! That’s what I say!”

Related story from us: The forgotten history behind the world’s most famous tongue twister

The same could be applied to the Humpty Dumpty origin story—it can mean just what you choose it to mean, neither more nor less.