You’ve seen this party trick, or maybe you’ve even done it yourself at a boring family dinner: dipping fingers into water in a crystal goblet and circling them around the glass’s rim to create a ringing sound. But brace yourself. For a time in the late 1700s, doing so was suspected of causing depression—or even becoming fatal.

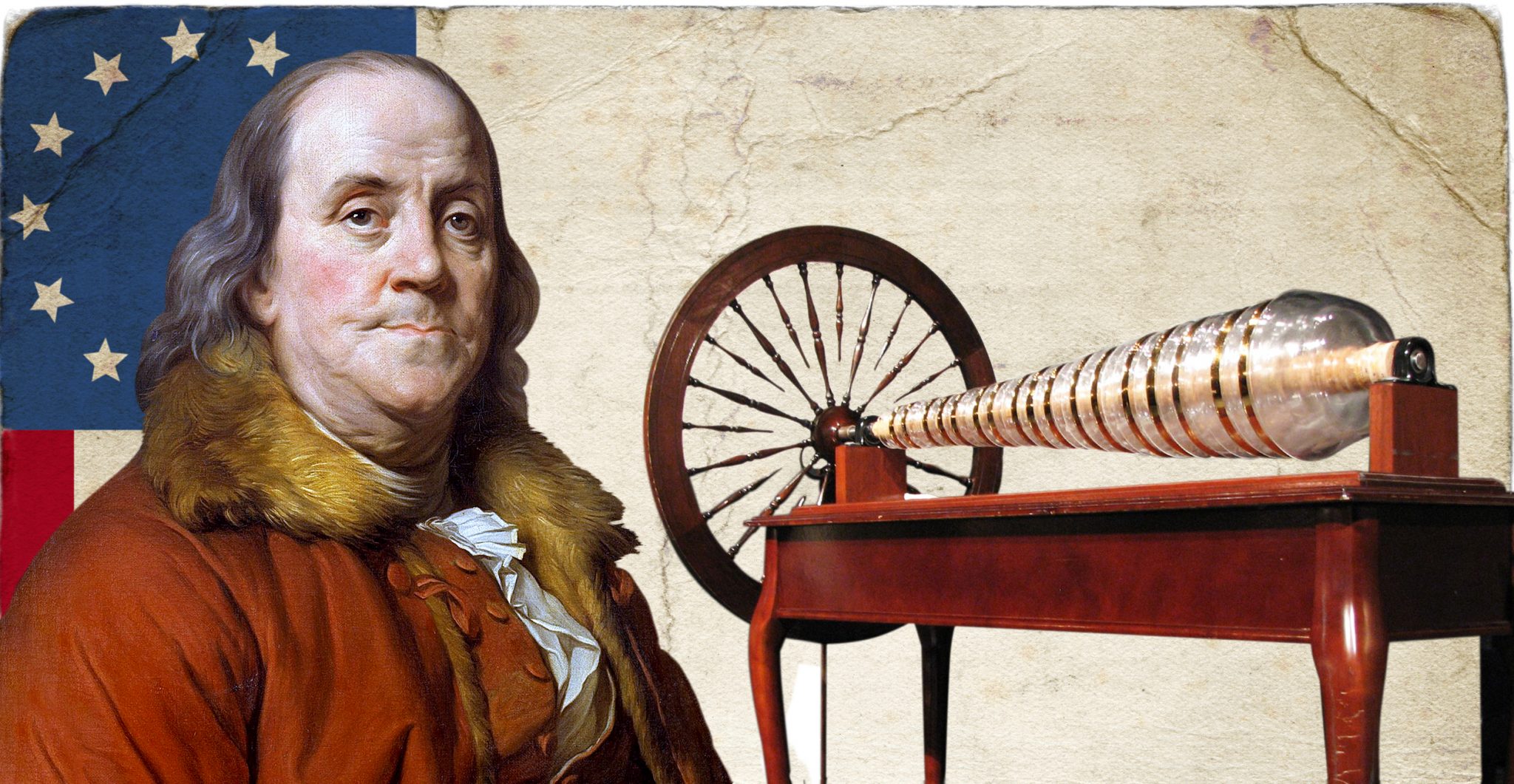

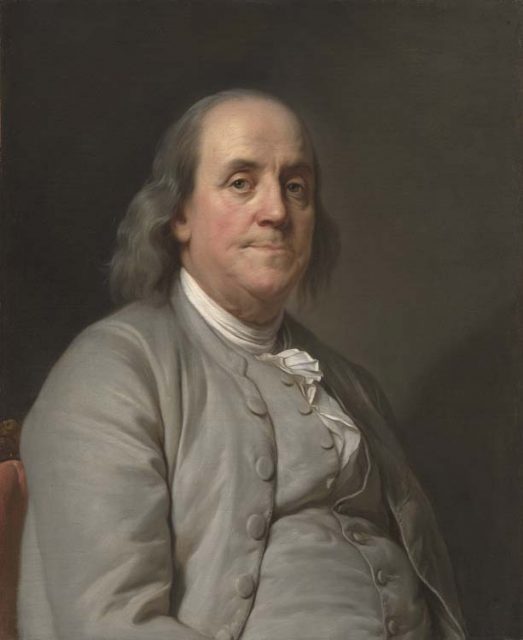

In England and France in the mid-1700s, musicians performing on “singing glasses” provided a popular form of entertainment. Founding Father and inventor extraordinaire Ben Franklin, abroad as a delegate for Colonial America, caught a performance in London. Intrigued, he put his mind to creating a musical instrument that worked on the same principles of fingers on glass.

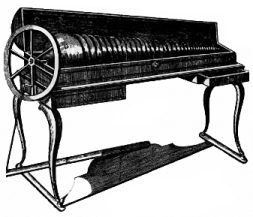

Franklin collaborated with a local glass blower, Charles James, to create a series of 37 glass bowls of graduating sizes, each with a hole in the middle so that they could link together horizontally on an iron spindle. He color-coded the bowls to identify the different notes. The rod was attached to a wheel, which in turn was attached to a foot pedal. Wet fingers touching the edge of the spinning bowls produced an eerie glass tone. Because the bowls were horizontal, a performer could play up to 10 notes at a time.

Franklin called his new musical instrument, which he completed in 1761, a “glass armonica” (or harmonica). The instrument made its debut in 1762, played by Marianne Davies, a flutist and harpist and relative of Franklin’s.

It was an immediate hit. Franklin took it with him on his travels—no easy feat, as the instrument composed of glass bowls was extremely fragile. He was himself a skilled enough amateur musician to play folk tunes.

The glass harmonica captured the imagination of a diverse array of professional composers, including Mozart, Beethoven, Saint-Saëns and Strauss. Its melodramatic sound found a natural home in opera, according to London’s Royal Opera House, with its most famous inclusion in the “mad scene” of Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor.

Perhaps it was the glass harmonica’s eerie sound that caused people to suspect the instrument was harmful, even dangerous. Some reported suffering tinnitus (or ringing in the ears) and disorientation when they heard the distinctive harmonica wail.

“The general idea was that playing the glass would cause maladies of the nerves,” according to the music-history book Performing Knowledge 1750-1850, edited by Mary Helen Dupree and Sean B. Franzel. “The ethereal sound of the glass harmonica, as an affecting power which impacts the body of the player directly, was thought to be the guilty party…. [It] fostered melancholy.”

People—especially women, who were thought to be particularly susceptible—were advised to play the glass harmonica only for a short time and never at night.

“If you are suffering from any kind of nervous disorder, you should not play it,” the German musicologist Friedrich Rochlitz wrote. “If you are not yet ill, you should not play it; if you are feeling melancholy, you should not play it.”

When a player named Marianne Kirchgessner died at age 39, the glass harmonica was blamed for poisoning her with lead. Never mind that she had pneumonia.

Indeed, lead poisoning was common in the 1700s and 1800s, but not from ingestion via the playing of glass harmonica. Lead compounds were used in medicine, food preservatives, and cookware, all of which had a more direct route to a person’s internal organs than an infrequently played musical instrument.

Franklin himself ignored the harmonica hysteria, and continued playing his invention to his death at the ripe old age of 84.

While it was enormously popular for a short period, like any fad, it faded. By the 1820s, glass harmonicas were all but forgotten. As they were highly breakable, few still exist today. The Franklin Institute in Philadelphia has one, as does the Boston Museum of Fine Arts; both are on display on rare occasions. A few modern artists have resurrected the archaic instrument for guest appearances in their songs, including Björk and Tom Waits.

While it’s unlikely that playing a glass harmonica is actually dangerous, there is one instrument that could kill you: the Tesla Coil. Invented by Nikola Tesla in 1891, this resonant transformer can create music via high-voltage sparks and carries enough electrical current to stop a not-careful performer’s heart.

Unsurprisingly, a Tesla Coil is displayed every year at the Coachella Festival, and has been incorporated into song by the experimental Icelander Björk. We don’t recommend using it for the song “American Pie,” because, as you know: “This will be the day that I die…”