Vincent Van Gogh may be as well known for his lunacy as his Starry Night. The artist who cut off his own ear and later committed suicide painted his most famous work from his room in an insane asylum. Indeed, Van Gogh’s troubled life and death serves almost as a definition of the tortured artist or mad genius.

He created 900 paintings, but sold only one during his lifetime. He wrote epic letters to his brother Theo, which document his brilliance and his delusions. Peripatetic in his career and appetites, he was driven by an eagerness to please that had the perverse effect of repulsing people. Were the seeds of his mental instability planted in his early childhood?

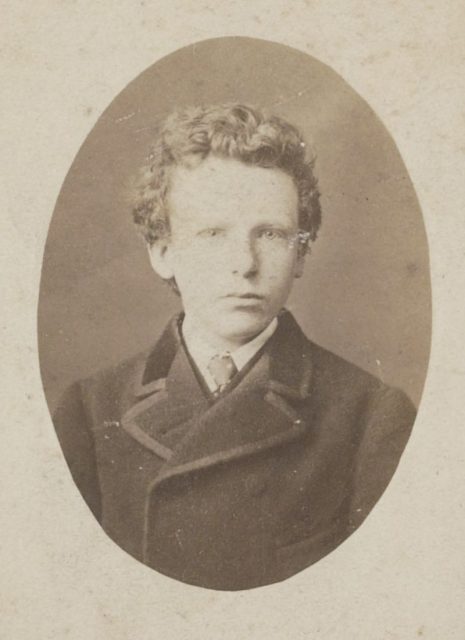

Vincent Willem van Gogh was born March 30, 1853, in Groot-Zundert, a small village in Holland that revered both the church and fine art. His father was a Protestant minister; his uncle was an art dealer. Exactly a year before his birth, his mother had delivered a stillborn boy, also named Vincent, after his grandfather. The heartbroken parents buried the infant and erected a tombstone bearing his name, which haunted the surviving Vincent. In his early childhood, he was home-schooled by his mother, a religious woman with a taste for art and nature who kept her family close, some say to the point of claustrophobia. When he was 11, young Vincent was sent to a boarding school, which he loathed, feeling abandoned.

During his melancholy school years, Van Gogh turned his attention to painting and learning languages, becoming conversant in French, English, and German, in addition to Dutch. But by the time he was 15, Van Gogh’s family was in financial straits, and he was forced to abandon his studies and go to work in his uncle’s art dealership. A few years later, in 1873, he was transferred to the gallery’s offices in London, where he thrived. He fell in love with the literature of Charles Dickens and George Elliot, as well as a young lady who by all accounts did not reciprocate his passion. Her identity is debated—some say she was his landlady’s daughter, others that she was a friend of the Van Gogh family. Regardless, the rejection precipitated his first mental breakdown. Paranoid and delusional, he became obsessed with the Bible and hostile at work, and soon lost his job.

Van Gogh embarked on a quest for a new identity. He was drawn to teaching and preaching—he craved attention even as he subverted authority. He taught in an English boarding school, where he delivered his first sermon. But his efforts were undercut by his abrasive personality. He prepared for entrance exams to theology school, but was denied entrance when he refused to study Latin. He volunteered to preach in an impoverished Belgian coal-mining town, whose population adored him, but he failed to impress his superiors, who told him to seek work elsewhere. With this rejection and seeming failure, Van Gogh sank again into depression.

The early 1880s saw Van Gogh bounce between artistic studies and romantic disasters, and he returned repeatedly to his parents’ home, straining their relationship. With the support of his younger brother, Theo, who’d taken up the family profession of dealing art, Vincent began formal study of anatomy and perspective in Brussels. In an extended stay with his parents, in Etten, he suffered another rejection and subsequent depression, when he fell in love with and proposed to a recently widowed cousin, who was decisive with her answer: “Nooit, neen, nimmer,” as he wrote to Theo (“No, nay, never”). His family and supporters were dismayed when he later moved in with an alcoholic prostitute, pregnant at the time with a second child. His mentor and cousin Anton Mauve, a successful painter, dropped Van Gogh because of his debauched lifestyle.

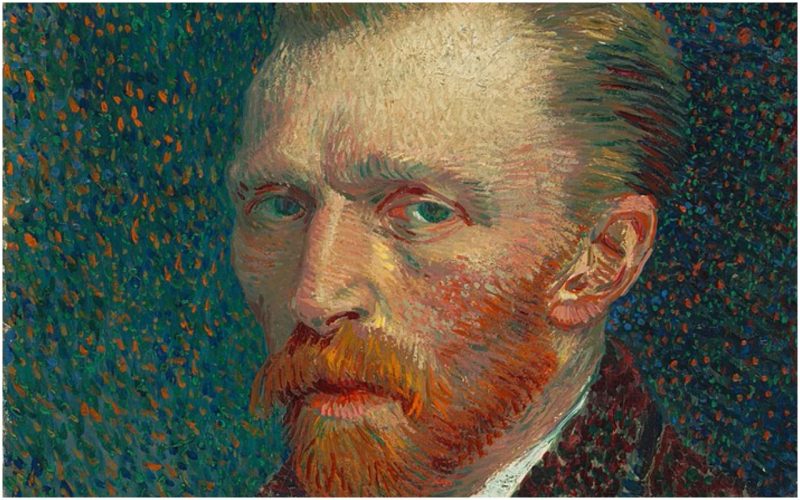

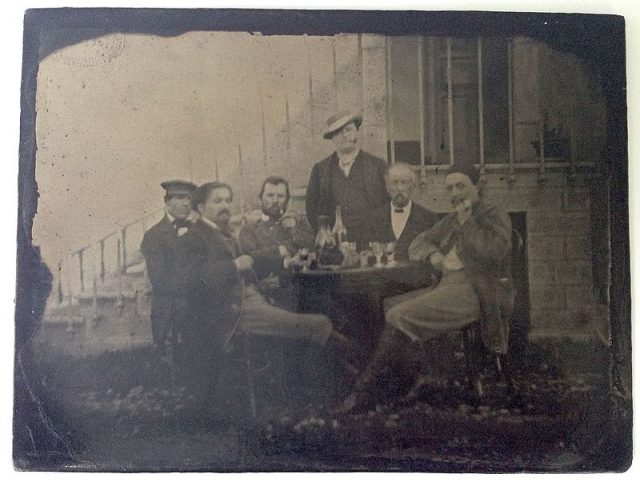

Through it all, he painted in his distinctive style, currently the subject of a new film, Loving Vincent. His 1885 The Potato Eaters marks what many consider the essential Van Gogh oeuvre. He moved to Paris in 1886, where he met some of the most radical painters of the day, including Claude Monet, George Seurat, Edgar Degas, and most notably Paul Gaugin, with whom the needy Van Gogh would have another tempestuous relationship. With passionate arguments in many drinking sessions, Van Gogh absorbed the Paris painters lessons on light and color.

As his artistry ascended, his madness deepened. In 1888, Van Gogh moved to southern France, where he rented the “Yellow House” in Arles, spending the money Theo sent him on paint and canvasses rather than food. He ate bread and drank coffee in the mornings, absinthe at night. He sipped turpentine, according to Biography.com, and sucked on lead-paint-laden paintbrushes, possibly poisoning himself.

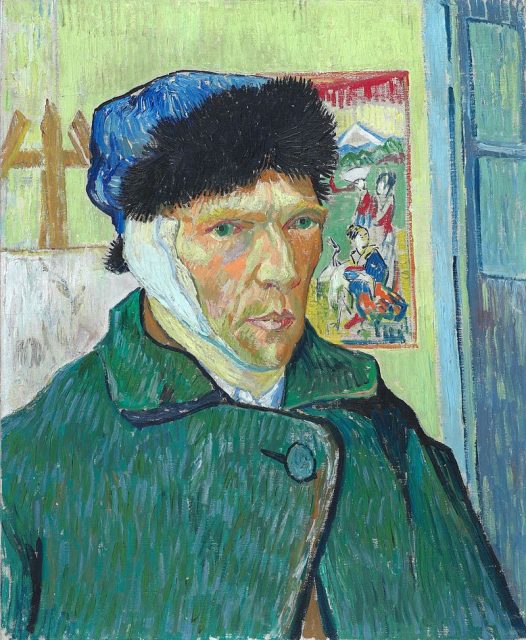

Worried about his brother, Theo paid Paul Gaugin to visit Vincent. Together they painted and argued, amiably enough at first, but tensions escalated when Gaugin was not suitably impressed with Van Gogh’s work. After an ugly fight on December 23, 1888, Gaugin stormed out. The distressed Van Gogh, in a fit, sliced off his left earlobe—later memorialized in his Self-Portrait With Bandaged Ear. He stumbled to a brothel, and presented the ear to a prostitute saying, “Keep this object carefully” (she promptly passed out). He was admitted thereafter to an asylum in Provence, where he painted some of his most renowned work, including Starry Night. While this was perhaps his most productive period, his mental state was precarious. He wrote to Theo: “The surroundings here are beginning to weigh me down more than I can say. … I need some air, I feel overwhelmed by boredom and grief.”

The year 1890 dawned auspiciously with the birth of Theo’s first child, also named Vincent, and the sale of Vincent’s painting The Red Vineyard. Vincent moved to Auvers to be under the care of a new doctor. He seemed healthy, and painted furiously. By that summer, however, Theo was distressed by financial difficulties and his infant’s ill health. Feeling himself a burden, Vincent walked to a field and shot himself in the chest. He staggered back to his house. A neighbor found him and summoned Theo, who was there when Vincent died two days later, saying, “ La tristesse durera toujours,” or the sadness will last forever. Theo would write: “I understood what he wanted to say with those words.” The madness would never leave Vincent alone, and so he left this world. He was 37.