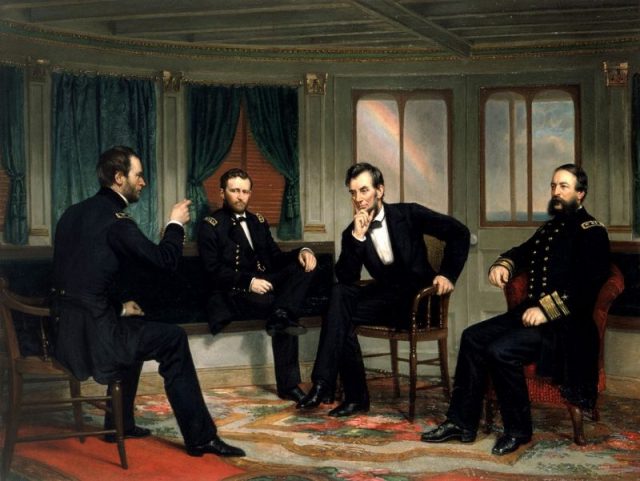

In 1864, Ulysses S. Grant became commander of all Union armies in the Civil War, winning President Abraham Lincoln’s confidence with his resilience and determination. His nickname was “Unconditional Surrender Grant,” and when Lincoln heard criticism of Grant, he once said, “I can’t spare this man–he fights!”

Few would have predicted greatness from Grant at the beginning of the war, however. Despite his having attended West Point and serving in the Mexican War, no one seemed to want him at command rank in 1861. After repeated efforts, Grant obtained a commission of lieutenant of a volunteer Illinois infantry, but only after a congressman intervened on his behalf.

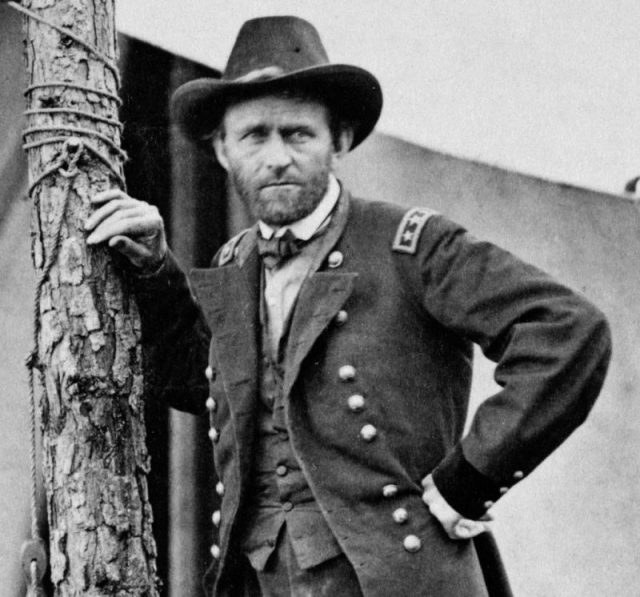

His background and demeanor were the opposite of the polished, aristocratic Robert E. Lee, commander of the Confederate forces. Grant was quiet, plain, unassuming, rough-hewn, the son of an Ohio tanner. He graduated 21st out of 39 in his class at West Point. After the Mexican War, he failed in several businesses, reduced to selling firewood on the streets of St. Louis in 1855. When the Civil War broke out, he was working as a clerk.

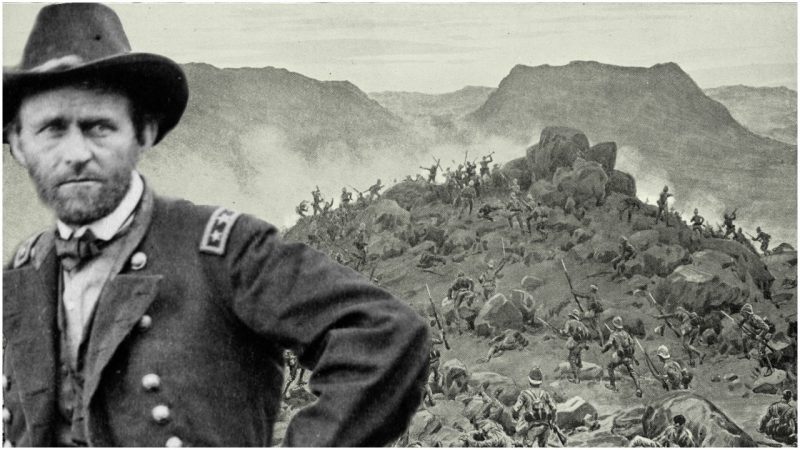

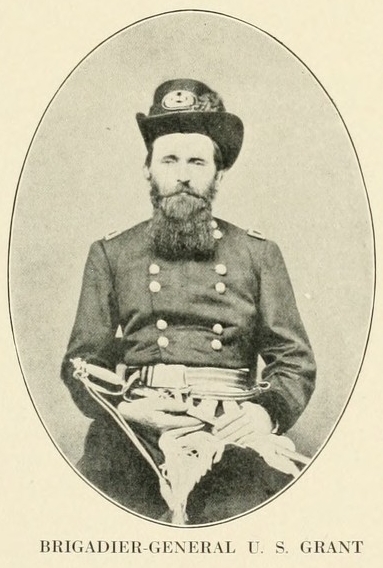

On August 5, 1861, Grant was made brigadier general of the 21st Illinois Volunteers. Three months to the day, Grant arrived with his men at Belmont, Missouri. It would be his first battle of the Civil War, and he was 39 years old.

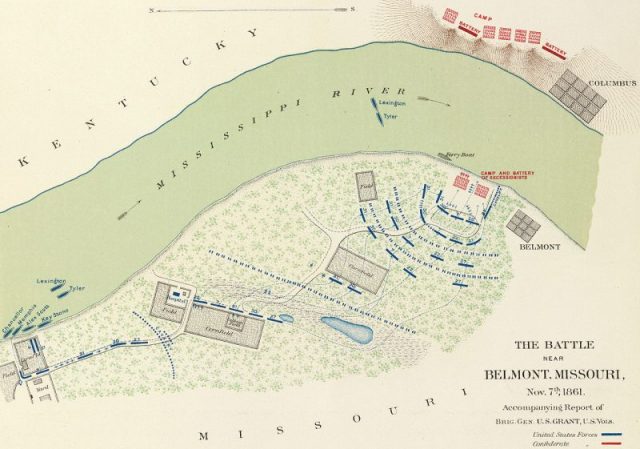

That November, Confederate soldiers were entrenched in the high bluffs of the town of Columbus, Kentucky, across the Mississippi River from Belmont. Columbus sat along a bend of the river where the Mississippi was only 800 yards wide. The bluffs commanded all the shipping that passed by, and the railroad nearby.

Whoever controlled Columbus had control of the upper Mississippi. Kentucky was a state of divided loyalties and a precarious neutrality. President Lincoln, a native of Kentucky, said that “to lose Kentucky is nearly the same as to lose the whole game.” But Confederate Major General Leonidas Polk had moved his forces into Kentucky and occupied Columbus.

For two months, Grant had prepared to move, drilling his soldiers. He had 20,000 men under his command, almost none of whom had ever fought in a battle. They were holding bridges and searching the countryside for elusive guerrilla leaders of the South. Grant’s troops were restless, and he decided to move from his base in Cairo with the objective of Belmont, and its small Confederate garrison.

In a dispatch, Grant wrote that an attack at Belmont “would probably keep the enemy from throwing over the river much more force than they now have there, and might enable me to drive those they now have out of Missouri.” On the evening of November 6, Grant’s men boarded a flotilla of five steamers to move down the Mississippi.

The other side assumed that Grant’s approach on Belmont was a feint, a diversion meant to draw Confederates away from the Columbus bluffs. Belmont was not really a town, more of a steamboat landing with a log house and a shed on a flat marshy elbow of land. The Confederates had built a small garrison.

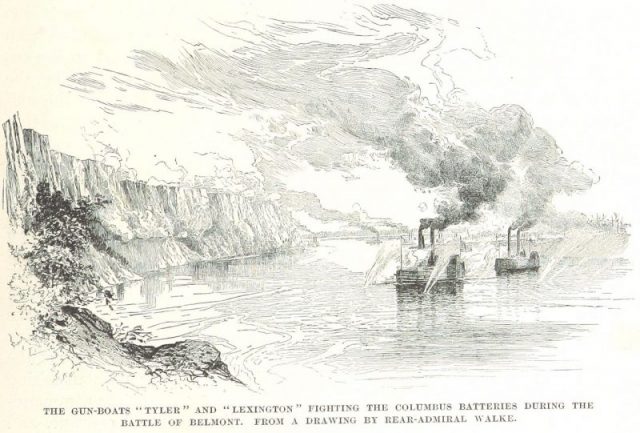

Once they realized the attack was genuine, Confederate regiments hurried to Belmont that morning. After much skirmishing, the two sides faced each other and fought in earnest. The Confederate batteries pummeled the Union lines while Grant rode up and down, shouting orders and encouragement until his horse was shot from under him.

The Confederates, with their backs to the river, put up a strong resistance, slowing the Federal advance, but they finally drove the Southerners to the riverbank and out of camp. The victorious Federals took more than 100 prisoners and rushed in to occupy their prize. Ignoring the fleeing enemy and overlooking two approaching transports loaded with reinforcements, the young Union volunteers looted the enemy camp, looking for food to eat and prematurely celebrating victory with cheers and cannon volleys.

The lack of discipline alarmed the veteran Grant, who described the men as being “demoralized from their victory.” In his first command as colonel of the 21st Illinois, he had curbed absenteeism, drunkenness, and disorderly conduct with threats of court-martial, imprisonment, and even execution. But in the heat of battle, Grant could not restore order. He saw the enemy, hidden by the steep riverbank, escaping north to the protection of the woods. He was also aware that Confederate reinforcements were coming.

Grant, in desperation, ordered the camp set on fire. When the smoke cleared, across the river, the Confederate forces realized their men were safe, and so they let loose with solid shot, shell, and grapeshot. The Union celebrations came to an abrupt halt. The infantrymen fell into formation and marched into the woods.

A new, more serious battle ensued, with Confederate reinforcements fighting Union troops who were exhausted. There was considerable confusion. The two forces exchanged volleys until a Confederate bayonet charge broke through. The morning’s roles were reversed as the Confederates emerged from the woods toward a Union force out in the open. Cries of “Surrounded! Surrounded!” rose up from the Federal ranks.

Many of the Union troops wanted to surrender. Grant announced that “we had cut our way in and could cut our way out just as well–it seemed a new revelation to officers and soldiers.” A battery was ordered onto a rise, and it blasted away with double shot and canister. A volley of muskets followed, which one Confederate described as a “blast of fire…full in our faces, a horizontal sheet of flame and bullets that took my breath away!”

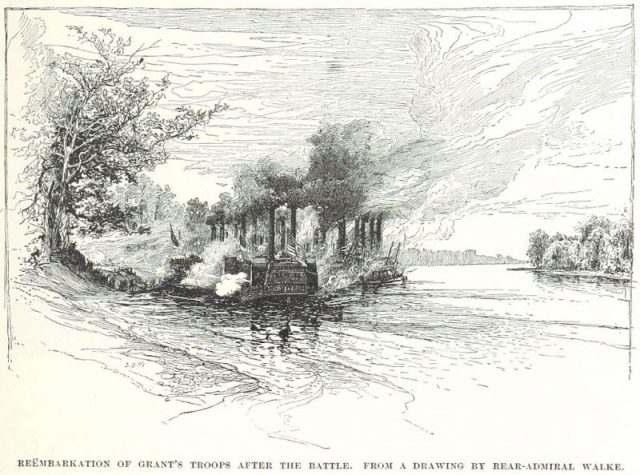

Fighting their way back to the landing, the Union men stopped to fire at the pursuing Confederates. When they finally started to board the river transports, the Rebels fired at them from the forest’s edge.

Grant had returned to a hollow where he placed the rear guard, only to find that they had already left. Grant went alone to check on the enemy’s progress. Wearing a normal soldier’s overcoat, he rode into a cornfield. Suddenly, Confederate troops appeared only 50 yards away. Camouflaged by the tall cornstalks, he slowly turned around and walked his horse away. Once at a safe distance, he began to gallop as fast as he could back to the landing. Later he learned that Polk had spotted him in the cornfield and invited his marksmen to take a shot. Not recognizing Grant as the opposing general, none of the marksmen did so, missing an opportunity that might well have changed the outcome of the Civil War and radically altered American history.

By the time Grant reached the river, the sun was starting to set. The continuing enemy fire had forced the boats to launch while Grant remained on shore. As they floated away, a plank was extended from Belle Memphis onto the riverbank. Grant’s horse slid down the muddy bank on its hindquarters, stepped onto the plank and trotted on board. With the last and most important Union soldier safely aboard, the transports left Missouri. Grant called in the gunboats to silence the Rebels on the shore.

At one point Grant, who had bee lying on a couch in the captain’s room, rose and went on deck to observe the activity. While he was on deck, a bullet penetrated the wooden ship and hit the couch in the exact spot where his head had rested minutes earlier. A second chance at changing history.

More than 600 casualties were suffered by each side; 175 Confederates were taken prisoner, and two guns were captured. The Columbus bluffs soon became irrelevant, outflanked in February 1862 by Grant’s capture of Forts Henry and Donelson. That same month the Confederates left Columbus. A month later, Union troops moved in.

Grant’s men learned important lessons at Belmont. The troops would eventually capture Vicksburg and win complete victory in the west. Belmont was a crucial turning point for Ulysses Grant. After his undistinguished service in the Mexican War and the 13 difficult years that followed, Grant had commanded troops in battle. In his memoirs he wrote, “The National troops acquired a confidence in themselves at Belmont that did not desert them through the war.” This observation describes Grant as well.

Max Eastern is the author of the noir thriller “The Gods Who Walk Among Us,” a winner of the Kindle Scout competition. To learn more, go to maxeastern.wordpress.com