We will all meet death someday. For many of us, it is unlikely to have been when we were very young unless we tragically lost someone close to us. However, for children in the 17th century, death was something they came to terms with from the moment they could read.

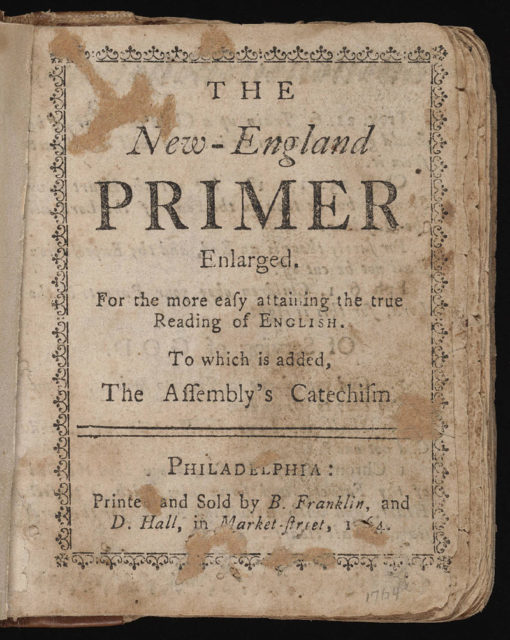

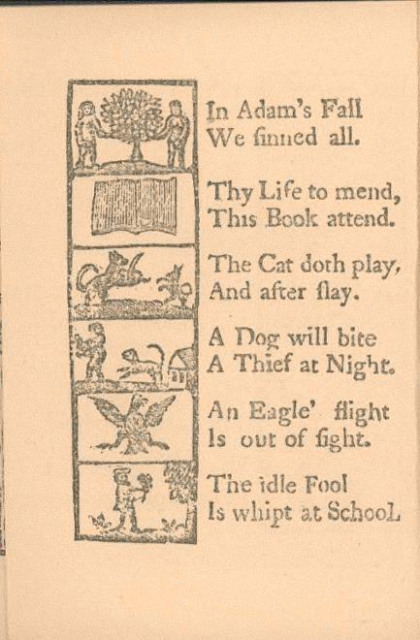

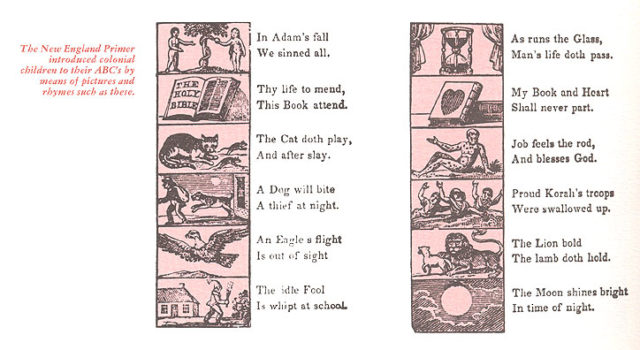

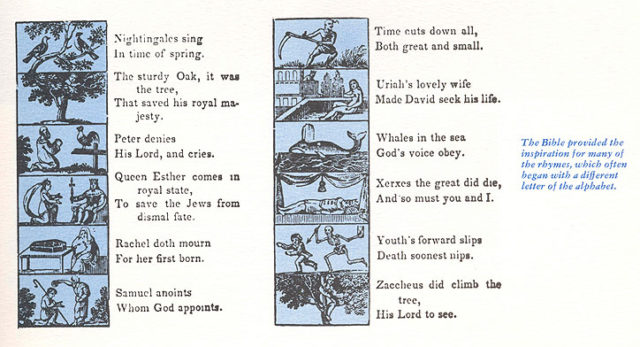

We have many variant copies of The New-England Primer, which was a book used to teach Protestant children their alphabet and how to read. The oddity of it (for us, of course) is that many of the lessons inside the textbook make mention of the frailty of life, impending death, and damnation. Imagine being a child and constantly considering the Grim Reaper just around the corner. More than just words, there are even pictures depicting this reality. Regarding the time in history, it really does make sense.

The New-England Primer was created to serve as a textbook to teach children how to read. It was thought that all people should be able to read God’s word, so it was important that everyone was literate. The New-England Primer was first used in Massachusetts where, around 1642, a law was passed promoting literacy among all people. In addition, all small towns were required to have a teacher, and larger towns were required to have schools.

It was considered important that all good Christians should be able to read God’s word for themselves, a reflection of the English Reformation. However, with an increase in demand for learning to read, there was a dire need for a proper book to prepare the children for reading the Bible. To answer this need, a man by the name of Benjamin Harris put together The New-England Primer.

This text, with fewer than 100 pages, taught the alphabet, syllables, and sentence formation, all while also using rhymes to teach lessons. Harris’s legacy became so popular that it is believed to have had 450 editions and six to eight million copies sold not only across the United States, but also in Britain and surrounding areas during the next 150 years.

Only about 1,500 known copies remain, ranging from various time periods. With these, we can understand the type of education experienced in early America. From the earliest productions, there are many references to death, hell, and salvation. Four examples that really bring this to light, beginning with learning the letter G, which has the rhyme, “As runs the Glass/ Mans life doth pass.” The picture for this sentence is merely an hourglass with the sand falling. As time passes, we will naturally become closer to death. While it does reference death, it is not as morbid seeming as the other examples.

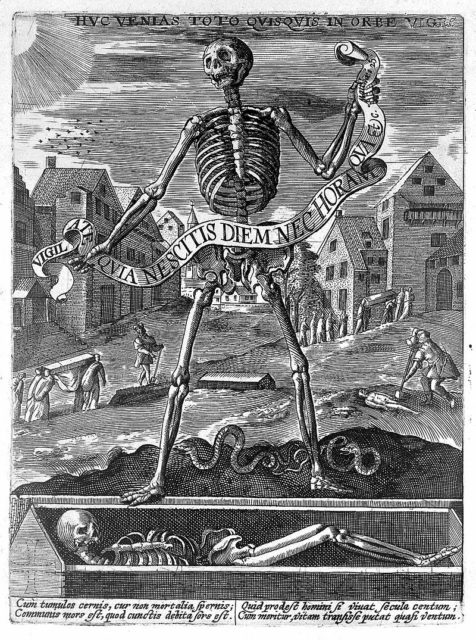

For Y, it states, “Youth forward slips/ Death soonest nips.” This passage is accompanied by an image of the Grim Reaper who appears to be stabbing a child in the head with an arrow. This child’s death in the image and warning in the phrase is, of course, reminding children that death can come even at their young age, as it did to many in those times. To further elaborate on this idea, T states, “Time cuts down all/ Both great and small.” Time is, as seen before, a reference to death, so this means that death is not picky when it comes to the old or young. These examples show that children were taught what can be seen in today’s world as almost terrifying lessons on life while learning their ABC’s.

Of course, while it is odd to us, such teachings make a lot of sense for Protestants during these centuries. For one, it was a time before cures for many illnesses, diseases, and other problems. Infant and child mortality rates were high. Weber State University shared statistics that include New England during the 1600s on child mortality. Their statistics range from 1607 to 1624. In New England, 180-200 of every 1,000 newborns died at birth.

In 2014 in the United States, this number has dropped significantly to 5.82 infant deaths per 1,000 births. Also in the early 1600s in New England, about 35 to 40 percent of children never reached adulthood. So, it is not a surprise that even children in the 1600s had to understand death, for even if it is not their own death, they were likely to see many people around them die.

In today’s education, we often shy away from teaching about life and death cycles for elementary aged students. Rather, we like to focus on more happy images: animals, plants, and any other sign of life. However, for those learning from The New-England Primer, life was something taught through death, and vice versa.

A quote from an old version of the book makes this clear with the statement, “Life and the Grave two different lessons give/ Life shews us how to die, death how to live.” So, these children were not shown just one side of time’s cycle; they were familiar with the good and bad.

Of course, for them, death was not really a bad thing. It was the stepping stone to bliss if the person lived a sinless life. Such teachings were required to ease the anxiety of death, which is very different from today’s lower death rates and more upbeat teachings for children.

The primer was used through the 18th century and into the 19th before it lost its dominance as a way to teach.