For some veterans of war, the conflict doesn’t end when the truce is signed. Psychological trauma haunts the people who have seen the horrors of combat. Still others refuse to accept that the war is over. Some even deny it.

Then there’s Hiroo Onoda.

The story of the Japanese intelligence officer who remained hidden on an island in the Philippines almost three decades after World War II ended became well known in 1974, and has become something of a testament to endurance since then, as Onoda spent 29 years essentially fighting a personal war.

The so-called Japanese holdouts were soldiers of the Japanese Imperial Army who refused to accept the surrender of their country and continued guerrilla activity in the regions where they were stationed.

Even though Onoda became the most famous of the holdouts, he wasn’t officially the last, with Teruo Nakamura surrendering a few months after him. But while Nakamura ceased combat activity as soon as the war ended and simply went into hiding, Onoda was responsible for several clashes with the Philippines police force and locals, decades after the surrender.

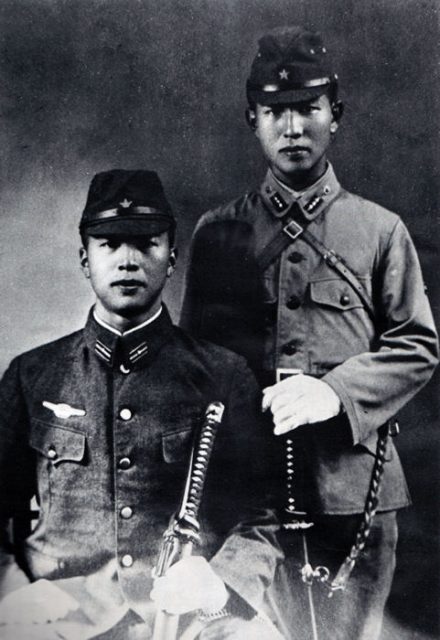

Hiroo Onoda was born in 1922, a descendant of a samurai family. His father served in the Imperial Army and was killed in China in 1943. In 1944, Onoda was stationed in the Philippines archipelago, on Lubang Island. The young intelligence officer was instructed to use any means necessary to disrupt the Allied attack on the island, which included the sabotage of an airstrip and a pier, so they wouldn’t fall into enemy hands. With his orders came an instruction―under no circumstances was he to surrender or take his own life.

Despite his orders, Onoda was reportedly prevented from conducting sabotage by senior officers on the island who were eager to surrender once the United States and Philippine Commonwealth forces invaded on February 28, 1945. Lieutenant Onoda, together with three other soldiers, escaped capture in the nearby mountains.

Private Yūichi Akatsu, Corporal Shōichi Shimada, and Private First Class Kinshichi Kozuka continued the fight under the leadership of Lieutenant Onoda, conducting minor acts of sabotage and engaging in several shootouts with the local police.

Even though they saw leaflets announcing the Japanese surrender, they dismissed it as enemy propaganda. Their mistrust was reinforced by the reaction of the police to their presence–police responded with gunfire when they saw the four-man group of Japanese soldiers.

By the end of 1945, leaflets had been dropped by air into the mountains in which the renegades took refuge. This time, the leaflet was signed by General Tomoyuki Yamashita, who commanded the Japanese troops in the Philippines and Indochina. Still they refused. Onoda studied the leaflet and concluded that the signature must have been false.

In 1949, Private Yūichi Akatsu sneaked out of the cell’s camp and surrendered to the local authorities. The call for others to surrender continued―at one point including distribution of photos and letters of the families requesting them to stop their resistance―but all in vain. Onoda and his two comrades-in-arms simply refused to believe that the war was over.

In 1953, Corporal Shimada was shot in the leg in a stand-off with some local armed fishermen. Even though he managed to recover, Shimada was killed the following year by a search party. Onoda and Kozuka managed to escape.

Private First Class Kozuka met his end in 1972, when a police raid disrupted their burning rice fields in a nearby village. The group became a real nuisance, with their stubborn refusal to face the fact that such acts of sabotage were nothing more than petty crime. Local villagers both hated and feared them, as their wartime mindset made them unpredictable.

By 1972, Onoda was on his own. Lacking the capacity to conduct further guerrilla actions, he settled down in the mountains, looking for means to survive.

Japan Once Planned to Blow Up America With 9000 Balloons

Perhaps he would have died in the forests of Lubang Island if it weren’t for Norio Suzuki, a Japanese explorer and adventurer who set out to find the missing Japanese officer. Suzuki stated that his quest included finding “Lieutenant Onoda, a wild panda, and the Abominable Snowman, in that order.”

Suzuki approached Onoda in 1974 and befriended him, finally convincing him that the war was over. In a 2010 interview, Onoda described the meeting: “This hippie boy Suzuki came to the island to listen to the feelings of a Japanese soldier. Suzuki asked me why I would not come out.”

Soon after their meeting, Suzuki headed back to Japan with photos of the renegade soldier, asking for an official permit from Yoshimi Taniguchi, who was a Major in the Imperial Army and Onoda’s commanding officer during the war. Taniguchi was living as a bookseller since the end of the war and was greatly surprised by Suzuki’s request. Still, it was the only way to get Onoda to surrender.

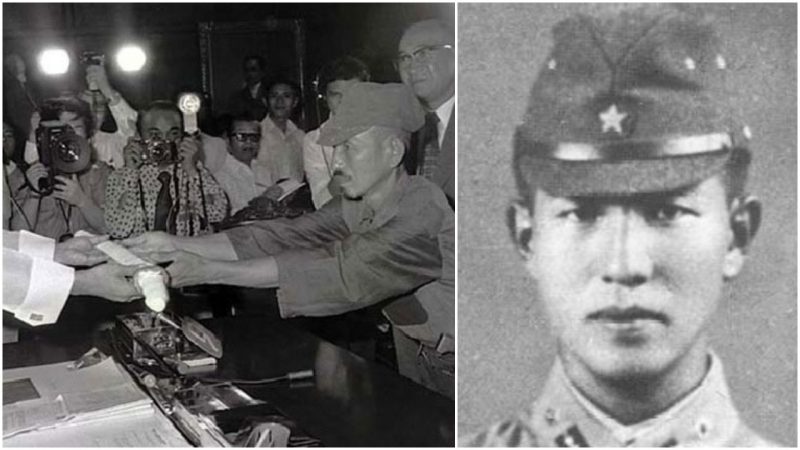

Taniguchi went to Lubang and officially accepted Onoda’s surrender on March 9, 1974. Hiroo Onoda was relieved of duty and offered his surrender. He turned over his sword, his functioning Arisaka Type 99 rifle, 500 rounds of ammunition, and several hand grenades. Also among the weaponry was a dagger that was a gift from his mother in 1944. The sole purpose of the dagger was to commit suicide if captured.

After he was repatriated, Onoda became celebrated by the Japanese public, garnering significant media attention. The president of the Philippines, Ferdinand Marcos, pardoned Onoda for his activities, which included several murders, due to this belief that the war was still on.

He became active in the public, advocating for a conservative policy in the midst of post-war liberalization. Onoda was also a resident of the Japanese community in Terenos, Mato Grosso do Sul, Brazil, where he lived from time to time.

Hiroo Onoda died on January 16, 2014, of heart failure due to complications from pneumonia. He remains a respected figure both in Japan and abroad. He continues to inspire some people, while others are troubled by the damage he did to the residents of Lubang.