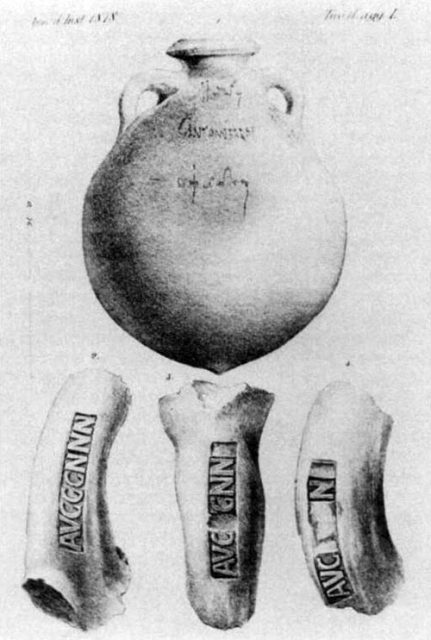

Our brains are wired to see ancient pottery behind glass, stored safe and sound in museums cases, piece by piece meticulously restored by archaeologists. But Monte Testaccio is the opposite–a mountain of archaeological garbage, the waste hill where millions of ancient Roman pottery shards, broken jars, and amphorae have piled up for over two centuries, since the times of ancient Rome. The site has not failed to provide archaeologists and researchers with details of how trade networks spread across the Mediterranean, some two millennia ago.

The 160-foot-high mound extends a farther 40 feet or so below the ground. It can be found in Rome’s Testaccio district, relatively close to the ancient port at Tiber River where goods were once unloaded as they came into the heart of the empire. Close by are the Horrea Galbae warehouses that were used to store the imported cargo, most usually olive oil or wine, but also other goods such as spices.

The estimates are 25 million broken pieces of amphorae, though some sources hint at a much greater number than this. Analysis of the shards has shown the pottery came from neighboring regions of the Italian peninsula such as the Iberian peninsula, but also territories overseas like Lybia and Tunisia.

The most prominent landfill of rubbish that the ancient Romans ever created, it has enabled researchers to obtain details of how sophisticated the trading network was in the Mediterranean two millennia ago, at the height of the Roman empire.

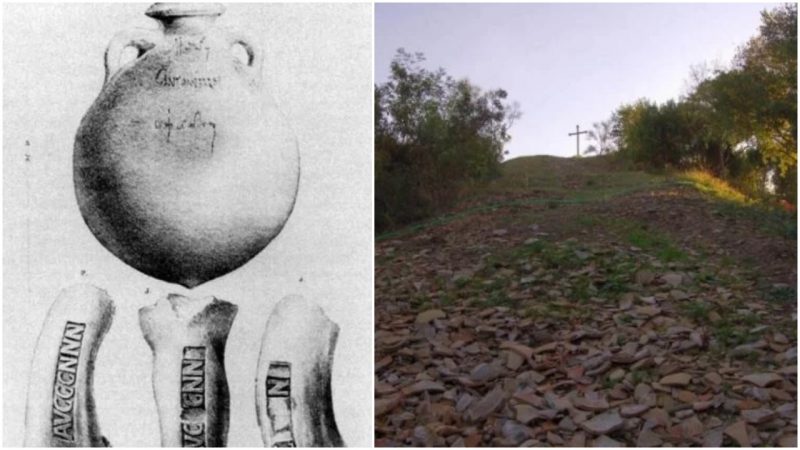

After unloading the imports at the nearby port, the amphorae were broken up and deposited at Monte Testaccio. The hill evolved into the largest testimony to the carvings and decoration used on the containers of trade-goods, particularly items like olive oil. Commercial inscriptions called “tituli picti,” similar to a modern-day customs notice, have been identified on a number of amphorae retrieved from the hill’s slopes.

These inscriptions have provided archaeologists with an exciting amount of information about these imported items. For example, where the olive oil was produced; how much a single amphora weighed and when it arrived in Rome; even details of how much tax was paid. Occasionally, some jars reveal the name of the ancient olive oil producer.

The first excavations on the strange hill were carried out by the Berlin-born archaeologist Heinrich Dressel, during the latter part of the 19th century. It was during later excavations, at the end of the 20th century, when it was confirmed that the site was intentionally made and was not just a place where waste from shipped goods was randomly dumped.

On the contrary, jars were decommissioned carefully, broken in half, and loaded onto the hill by carts pulled by mules. This had to be done as the amphorae were not reusable after the first shipment; its oil or wine contents simply made the clay stale and stink after some time.

The entire waste-management process was taken seriously. It was supervised by special officers, who made sure that the broken pottery was properly deployed on the dump to avoid landslides or any other accident. A good portion of the examined jars have been dated to the latter half of the 2nd century A.D. as well as to the first half of the 3rd century. In their intact form, many amphorae would have been quite big, weighing about 65 pounds if empty, and exceeding the weight of 215 pounds when filled with some of the precious liquids.

According to The Daily Telegraph, research has shown that a considerable portion of the imported olive oil originated in the ancient Roman province of Baetica, or what would nowadays be Andalusia. Therefore, Spanish archaeologists have frequently been engaged in the excavations and research at the site so that details of related finds are established with higher accuracy.

The ancient Romans started to abandon Monte Testaccio around the 5th century A.D. as their empire crumbled. In the following centuries, the Mount of Shards started serving other purposes, as a frequently visited venue for various festivities, entertainment games, and jousting events.

Some of these events were unpleasant, such as those instances involving carts filled with pigs, pushed down the steep slopes of the hill from atop of it. The carts normally would have smashed to pieces at the foot of the hill, and the wounded animals were later slaughtered and served at feasts. In more normal circumstances, the site has been used as part of re-enactment processions of the crucifixion of Jesus.

The area became part of modern-day Rome as the first urban neighborhoods began to appear nearby, ahead of World War Two. The region developed at a faster pace after the end of the war, when next to it houses, stores, and restaurants mushroomed.

In the past, caves have been built into the foot of the man-made hill, and some of them are at present used as storerooms. Notably, some wine producers use these facilities to store their wine. The amphorae shards composing the hill are perfect for regulating an optimal temperature needed for keeping the wine.