Humans walked on the North American plateau as early as 13 millennia ago, according to new findings by researchers who have identified well-preserved footprints that were left by two adults and an infant. The ancient tracks were found on a Canadian island, off the country’s west coast. Given the age of the footprints, these are now considered the oldest so far encountered on the continent, a new study issued in the journal PLOS One on March 28, 2018, reveals.

The discovery backs up claims that the earliest people to migrate to North America came from Asia via a route that at the time was free of ice. The early arrivals then traveled all the way down along the coast to arrive at what is currently British Columbia. The first footprint, lurking in a brownish clay, revealed itself two feet under the surface on a beach on Calvert Island in 2014, roughly 60 miles away from Vancouver Island.

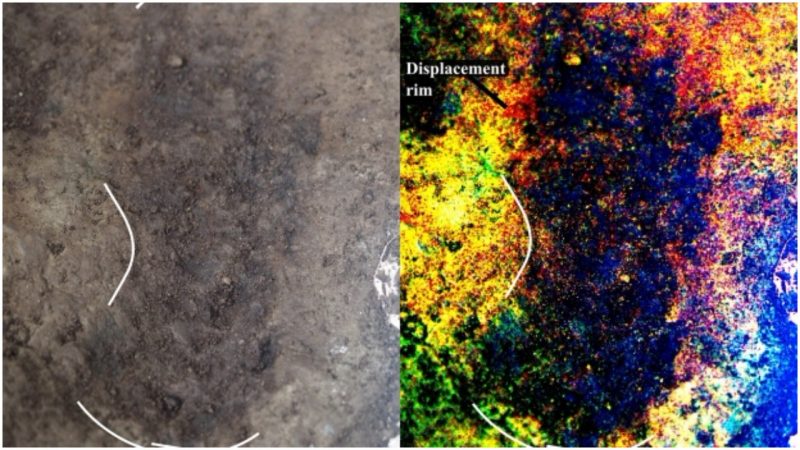

The research team’s decision to continue the exploration on the same site over the next two years proved fruitful, as more footprints resurfaced. The prints were of different sizes and led in various directions. A greater portion was found of the right feet, each one barefoot, and with clearly defined toes, arch, and heels, meaning these were not the traces left by a grizzly or another animal.

As the experts explain, these tracks survived because they would have hardened very quickly after being indented into clay that was probably very wet, and then buried by sand brought by the tides. The surrounding area where the prints were revealed is nowadays overwhelmed with thick bog and almost impenetrable forests, meaning the research team could access the beach only by boat.

Lead author of the study is anthropology expert Duncan McLaren from the University of Victoria and the Hakai Institute. The research team was joined and supported in the field by representatives of the Heiltsuk First Nation and Wuikinuxv First Nation. The study results point out that people were out there, in the wilderness, roaming the west coast of British Columbia some 13 millennia ago, in times when the coastal zones would have been stripped of ice as the last ice age was coming to its end.

McLaren said that “it is possible that the coast was one of the means by which people entered the Americas at the time.” The geography of the region would have significantly differed from today, as the sea levels would have been up to 10 feet lower between 11,000 and 14,000 years ago, with vast quantities of water still contained in enormous glaciers that later melted.

Except for the footprints, there weren’t any other significant finds or evidence of any settlement in the area. The ancient visitors to the island must have sailed to the location, as it was still an island back then, making use of a particular type of watercraft, McLaren says. They might have come here merely to explore the area or maybe to collect food and other resources.

So far the earliest known site associated with prehistoric humans and their presence on the western coast of the continent is in Washington state, the Olympic Peninsula’s Manis Mastodon site. There, archaeologists found a bone artifact carved into a pointed weapon, believed to be a spear tip and dated as some 13,800 years old. The remains of the earliest known such site on Canadian territory is at Charlie Lake Cave, also in British Columbia, where multiple artifacts including a weapon made of stone have previously been found.

The latest field expedition on British Columbia’s Calvert Island was not without challenges for the researchers, especially considering the inaccessibility of the excavation terrain. However, their focus on the tidal zone of the beach site has paid off, and their results suggest that expeditions in the future should also concentrate on other potential sites along this stretch of coastline–maybe more details will be revealed nearby of how early people traversed this part of the world.