There were many twists in the Civil War, but among the strangest is the case of St. Albans Raid.

It was an odd instance of Confederates going into Canada in order to wage war on the Union’s northernmost reaches. The raid took place in Vermont, the first state to ban slavery when it drew up its constitution in 1777. It was an area where there was little doubt where loyalties stood.

On Oct. 10, 1864, when several strangers came to town saying they were visiting from Canada for a sporting vacation, the people of St. Albans took them at their word. Even then, autumn in Vermont was an attraction. The three, however, were actually a group of Southerners lead by a brash Kentuckian by the name of Bennett Young. While in Canada, the 21-year-old lieutenant and the others worked meticulously on plans to try to disrupt the Union’s war efforts.

Young had already made several visits on his own to check out the town, which was also the home of Vermont’s presiding governor. He even visited the governor and his wife, claiming to be a theology student from Canada.

All the while he worked at charming the locals, Young was seething inside. He wanted revenge. Union Major General Philip Sheridan had beaten his forces through the Shenandoah Valley and struck a severe blow, burning barns, mills and grain, and seizing livestock, including most of the area’s horses.

Young wanted people on the Union side of the war to feel similar pain–and on a widespread level. As one of his co-conspirators wrote, “St. Albans will merely be the starting point … of a system of warfare which will carry desolation all along the frontier. There will be war to the knife and to the hilt … The towns will be burned and be pillaged.”

Young also had a more personal score to settle. He had been one of John Hunt Morgan’s Raiders until his capture in 1863. He was sent to Camp Douglas north of Chicago, a prison widely known for its terrible conditions. He escaped and eventually got back to Richmond, Virginia, expecting to rejoin the fighting as he had before. Instead, he was assigned to a clandestine effort funded by the Confederate Congress, which had set aside $1 million to destabilize the North through activities launched from Canada.

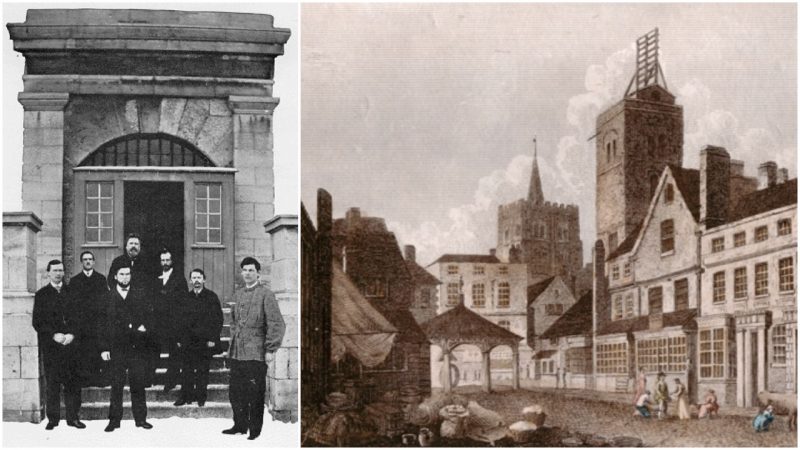

Young and his men laid low at the American Hotel in town and began bringing in more men, these pretending to be fishermen, horse traders, and hunters. The handsome Young even went out with a woman who had come to the town in search of work at the mills.

But finally, the “Vairmont Yankee Scare Party,” as the group of raiders called themselves, was ready to act. And on Oct. 19, 1864, the town learned what the men were really up to. From the steps of the American Hotel, Young issued a proclamation to stunned townspeople: “In the name of the Confederate States, I take possession of St. Albans!”

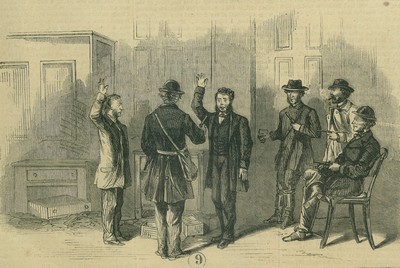

Meanwhile, the other men set to work in a 20-minute effort to destroy the market town. Many were assigned to rob the town’s three banks; a handful would steal horses to aid their escape; two would set fire to key buildings with liquid accelerant; some would guard the townspeople they captured and hold them on the town green while the terror unfolded.

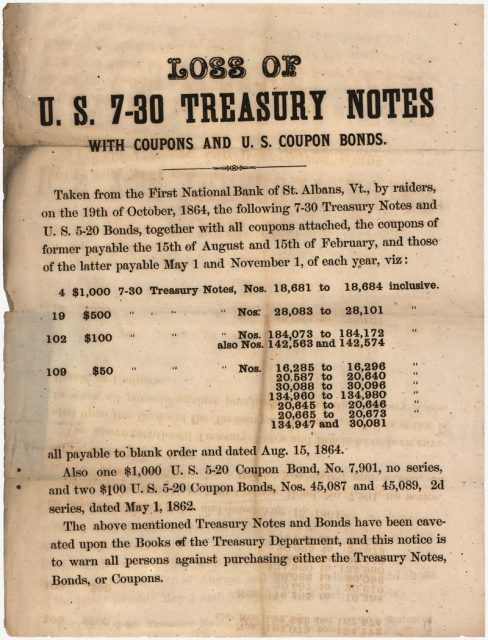

The bank robbers managed to get $208,000 from the establishments, although they missed a significant amount of money. The effort to burn the town was a bust. The accelerant wouldn’t take hold and only a shed was lost to fire. During the attack, several armed villagers put up a fight. One was killed, another wounded. Meanwhile, Young and his band made a dash back to Canada, with armed Vermonters giving chase.

What followed in Canada was a complicated string of trials and retrials. In the end, Canada paid some modest restitution to the banks.

The St. Albans Raid, although bold and well-planned, backfired for the Confederate effort in the long run. Canadians were less supportive of the South when news of the events unfolded widely and how their country had been used.

Meanwhile, the Union, understandably miffed, enacted stiffer passport regulations and repealed a decade-old trade agreement with its northern neighbor that had eliminated tariffs on fish, raw materials, and farm products.

Terri Likens‘ byline has appeared in newspapers around the world through the Associated Press. She has also done work for ABCNews, the BBC, and magazines that include High Country News, American Profile and Plateau Journal. She lives just east of Nashville, Tenn.