The people of the remote Appalachian Mountains often complain that they feel like an afterthought to the rest of the world. That sentiment is rooted in an actual history of neglect.

Early in the formation of the United States, the mountain settlers were so fed up with a stalemate over control that they took matters into their own hands. They created their own state–one that ended up acting like an independent country on U.S. soil for four years.

Welcome to the lost state of Franklin.

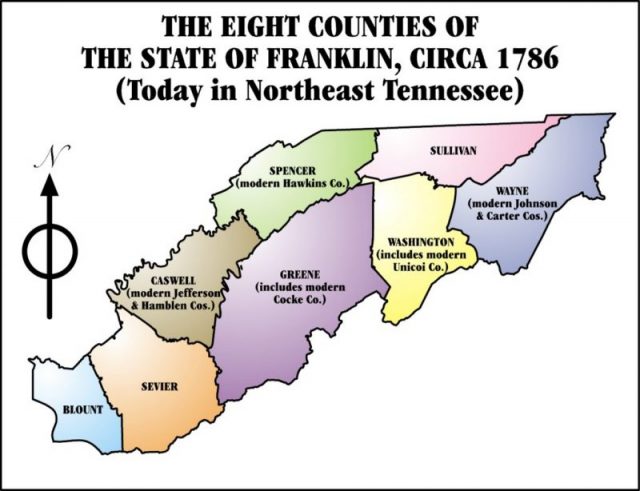

After the American Revolution, many frontier families lived in upheaval in a large swath of what is present-day East Tennessee. North Carolina claimed the territory, but its leaders were vacillating on what to do with it. Finally, they decided to pay off the state’s portion of the Revolutionary War debt by handing off the land to Congress.

That decision didn’t stand. Before the transfer was made, the Tar Heel State had an election and the newly elected leaders decided instead to keep the land.

Meanwhile, the residents of the territory were left without support from either state militias or federal troops in a time when Native American attacks were a real possibility.

They also feared that Congress, if it had control, might sell the land to France or Spain to pay its own war debt.

The mountaineers took matters into their own hands. On August 23, 1784, led by Revolutionary War hero John Sevier, a group of 50 settlers came together in the frontier town of Jonesborough and declared their independence from North Carolina.

In its earliest incarnation, the new state was called Frankland but later changed to Franklin in an effort to curry favor with statesman Ben Franklin. That tactic didn’t work.

“I am too little acquainted with the circumstances to be able to offer you anything just now,” wrote Franklin, who had been in Europe when the state was being formed.

In 1785, the mountaineers applied to Congress for statehood. North Carolina representative steadfastly opposed, but seven other states – a majority at the time – gave their blessings. That wasn’t enough; a two-thirds majority was needed.

Had it been approved, Franklin would have been the Union’s 14th state.

The self-reliant mountaineers still didn’t back down. Franklin continued to function without recognition from the federal government while its population exploded. In less than a year, 10,000 new families moved in.

Its governing blueprint, the Holston Constitution, was adopted, ironically mirroring much of what North Carolina had included in its own.

And although the new government start up wasn’t exactly smooth, the area had a lot to offer, including a clause in which all citizens were granted a two-year reprieve on paying taxes. Rather than initiate its own currency, Franklin operated on barter. Government officials were often paid in deer skins and apple brandy. Sevier proposed to commission a state flag, but it was never done.

Meanwhile, the Franklin lawmakers made peace with many of the Native Americans.

North Carolina continued to court Franklin residents, and soon swayed some of them. In 1786, it offered to waive all back taxes if Franklin would return to the fold.

The offer was dismissed in 1787, and North Carolina brought out the guns. It moved in with troops and re-established its own courts, jails, and government at Jonesborough, while Franklin officials operated nearby in their capital of Greeneville. Conflict escalated as the two rival administrations competed side by side. After a series of skirmishes, Sevier tried to place Franklin under Spanish rule, which incensed North Carolina.

Finally, Franklin–or at least most of it–gave up its fight and rejoined North Carolina, which quickly ceded it to the federal government.

In the end, the land became part of the new state of Tennessee.

Sevier, who was at one time under arrest by North Carolina, became its first governor.

Terri Likens‘ byline has appeared in newspapers around the world through The Associated Press. She has also done work for ABCNews, the BBC, and magazines that include High Country News, American Profile, and Plateau Journal. She lives just east of Nashville, Tenn.