When volcanic Mount St. Helens began to show signs of erupting in March of 1980, photographer Robert Landsburg wanted to capture every image he could of the Earth exerting its power. He had grown up in Seattle, Washington, and the mountain was part of his internal landscape.

For two months, while earthquakes sent shudders through the area, Landsburg picked his way around the Washington State high country to document what was happening.

Meanwhile, as if announcing its ill-tempered intentions, the mountain vented steam. Magma from deep within the Earth’s center crept higher and higher, elevating the tension in the area as it rose. Mount St. Helens’ sides bulged and cracked.

On the night of May 17, the 48-year-old freelance photographer based in Portland, Oregon, camped nearby. There’s irony in an entry in his journal from the night: “I feel like I am on the verge of something.”

On May 18, with Landsburg just four miles away, the peak started changing dramatically. Its north face began to slough away in what has been called history’s biggest landslide.

Mount St. Helens was beginning to blow.

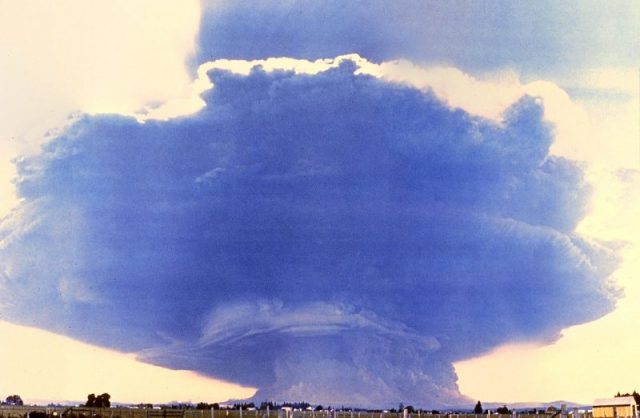

Frantically, Landsburg shot frame after frame as a billowing cloud of smoke and ash spewed and began its approach. As it moved closer, Landsburg realized this was his last stand. There would be no escaping the hot, poisonous gases and suffocating ash. Instead of panicking at his impending doom, Landsburg methodically took a series of actions for which he has been applauded. He rewound his film back into the canister, placed the camera in his backpack, and laid down over the bag to protect it.

His selfless act was realized after his body, buried in a moonscape of ash, was found near his station wagon. He had died of ash asphyxiation. Landsburg’s film was developed and provided geologists a valuable firsthand look of the eruption.

The following year, National Geographic published Landsburg’s last day of work. In an accompanying story, the magazine’s editors noted: “It contained not only telling images of the killing edge of the blast, but also the scratches, bubbles, warpings, and light leaks caused by heat and ash, the very thumbprint of holocaust.”

Landsburg was one of 57 people who died in the blast. The death count could have been much higher, authorities reported, but the eruption was on a Sunday, a day when area loggers were not at work.

Among others who died was Harry R. Truman, an 83-year-old innkeeper who refused to leave the area no matter how many people begged. His remains were never found.

Also killed was volcanologist David A. Johnston, who had been stationed nearby at Coldwater Ridge. While Johnston was the first to report the final eruption, his excited radio transmission was also his famous last words: “Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!”

A photograph shows Johnston happily sitting beside a camper hours before the blast, but his body was never found. The site he was stationed was hit by a shockwave of super-heated gas and ash.

One other photographer was killed by the volcano. Reid Blackburn worked for The Colombia newspaper, but also was shooting for National Geographic and the U.S. Geological Survey. He was stationed near Johnston at Coldwater Camp. Blackburn was an avid hiker and Mount St. Helens was one of his favorite hiking spots. He was said by colleagues to lovingly refer to the mountain as “the Sleepy Beauty of the Northwest.”

His car and nearby, his body, were found deeply buried in ash four days after the eruption.

More than 500 million tons of ash were belched out by the eruption, most of it in Washington, Idaho and Montana, but pockets of ash even made it to Oklahoma.

Traces drifted all over the world, some of it remaining in the atmosphere for several years.

Terri Likens‘ byline has appeared in newspapers around the world through The Associated Press. She has also done work for ABCNews, the BBC, and magazines that include High Country News, American Profile, and Plateau Journal. She lives just east of Nashville, Tenn.