Not far from the Alaskan panhandle is Stewart, British Columbia, which gets an average snowfall of 73 inches a year. The climate is not quite as harsh as one might expect, because the Canadian community is so close to the ocean, with an average high temperature during the winter of 13 degrees Fahrenheit. Stewart covers 216 square miles but has a population of fewer than 500 permanent residents. In the summer, from a safe distance, visitors thrill at the sight of Alaska brown grizzlies and black bears; in the winter, it’s heli-skiing time.

On June 25, 2022, a number of deeply enthusiastic people will arrive at Stewart, but only to proceed 45 minutes north to a remote, hard-to-find site of colder temperatures atop a glacier they call with reverence “Outpost 31.” This place was once a film location: Outpost 31 is the name of the scientific outpost overrun by a terrifying alien being in John Carpenter’s 1982 film The Thing. The alien can duplicate other life forms, and does so, taking over the humans at the outpost one by one until the few humans left realize what is happening and fight back.

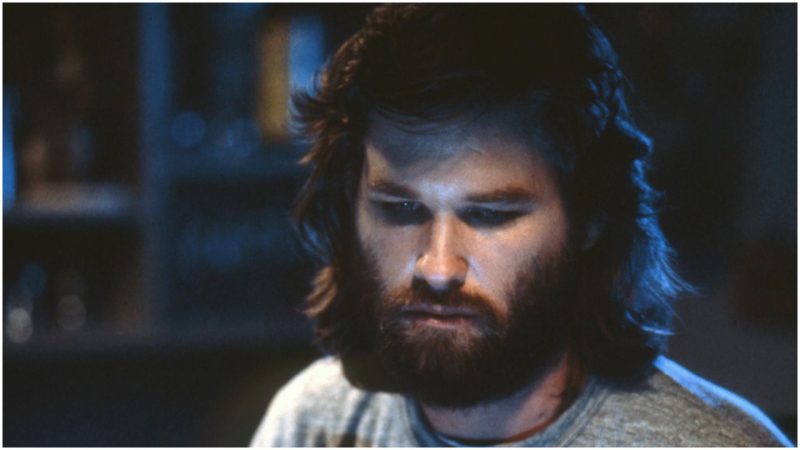

When it was originally released on June 25, 1982, shortly after the premiere of E.T. the Extra-Terrestrial, Carpenter’s The Thing, starring Kurt Russell, was widely panned, even scorned. But since then it has grown into being one of the true cult classics of film, with devoted fans who pay homage to its atmosphere of peerless paranoia, its stomach-clenching suspense, its groundbreaking special effects by Rob Bottin, and its musical score by Ennio Morricone.

The film is not only cherished by fans of science fiction and horror but also by those who work in Antarctica today. Although they built the set on a British Columbia glacier, it is meant to fill the story’s requirement: a U.S. scientific station in Antarctica, manned by about a dozen biologists, meteorologists, geologists, physicists, and support staff. Each year, the real men and women who winter-over at the Amundsen–Scott South Pole Station, where it reaches -80 degrees, do the same thing the first full night of winter: they gather to watch The Thing, followed by a special dinner.

The film has spawned merchandise ranging from board games and video games as well as a novelization, making-of documentaries, video analyses of the controversial ending, comic books, and a 2011 prequel starring Joel Edgerton and Mary Elizabeth Winstead.

As for the committed fans who plan to travel to British Columbia in 2022, they coordinated their efforts through a comprehensive website called Outpost31.com, with the tagline “Man Is the Warmest Place to Hide.” The anniversary page says, “Some fun ideas we have planned are a live video tour of the site, spending a night (or two) camping out at Outpost #31 complete with bonfire, and a viewing of the movie literally ‘on location’ synched live with fans around the world!”

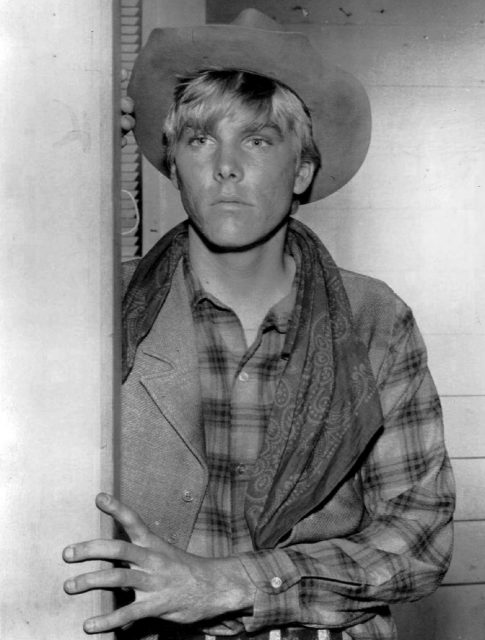

When it came out in the 1980s, The Thing was billed as a remake of a classic science fiction film of 1951, directed by Howard Hawks and called both The Thing and The Thing From Another World. As do many of the sci-fi films of the 1950s, it pondered the questions of whether man was bringing technologically spawned horrors on himself and if alien beings could be the friends of human scientists.

In John Carpenter’s version, no one wants to be friends with The Thing. Carpenter went back to the same source the 1951 film did: the 1938 novella Who Goes There?, written by a man who may not be a household name but who had an enormous influence on science fiction and wider popular culture: John W. Campbell Jr. He was the editor of magazines such as Astounding Science Fiction, had a strong influence on Isaac Asimov, and published Robert A. Heinlein, Theodore Sturgeon, and A. E. van Vogt.

Campbell’s novella Who Goes There? tells the story of a group of Antarctic scientists who discover an alien spaceship buried in the ice, which crashed hundreds of thousands if not millions of years ago. They thaw out its alien pilot but are for a while unaware that it is imitating the humans to the last detail–after killing them. Once it has taken over a human, the alien talks and behaves like the original, and is nearly impossible to detect as an imitation. Once the scientists realize what is happening, they struggle to identify who has been replaced in an atmosphere of terror and paranoia. Assistant commander MacReady comes up with an effective test: taking blood from each person and dipping in a heated wire to see the blood’s reaction. In the end, only three survive after a murderous struggle with the devious Thing.

The writing of the novella has a gritty, cynical atmosphere to it. It begins this way: “The place stank. A queer, mingled stench that only the ice-buried cabins of an Antarctic camp know, compounded of reeking human sweat, and the heavy, fish-oil stench of melted seal blubber.”

It is believed that Ridley Scott’s 1979 film Alien took its dark, cynical tone and atmosphere of uneasy, isolated colleagues from Who Goes There? as well as some aspects of its alien-feeding-on-humans plot. Certainly the classic 1956 sci-fi film Invasion of the Body Snatchers was heavily influenced by Campbell’s novella.

John Carpenter, at that time most famous for directing 1978’s Halloween, loved the original novella and was particularly excited by the challenge of filming the blood-test scene. He worked with Bill Lancaster, also an actor, on the script, and he cast Kurt Russell, his leading man from Escape From New York, as MacReady, now a heavy-drinking helicopter pilot, as well as Wilford Brimley, Keith David, Donald Moffatt, Richard Dysart, David Clennon, and Richard Masur, all giving strong performances.

In this version, the men at Outpost 31 become aware something’s wrong when a Norwegian helicopter flies into camp trying to kill a dog running away from them. Both Norwegians, who seem insane, die, and the Americans “adopt” the dog, completely unaware it is a Thing. MacReady takes a leadership role in the life-and-death struggle, and at one point, standing in a circle with his supposed colleagues in a blizzard, says, memorably, “I know I’m human. And if you were all these things, then you’d just attack me right now, so some of you are still human. This thing doesn’t want to show itself, it wants to hide inside an imitation. It’ll fight if it has to, but it’s vulnerable out in the open. If it takes us over, then it has no more enemies, nobody left to kill it. And then it’s won.”

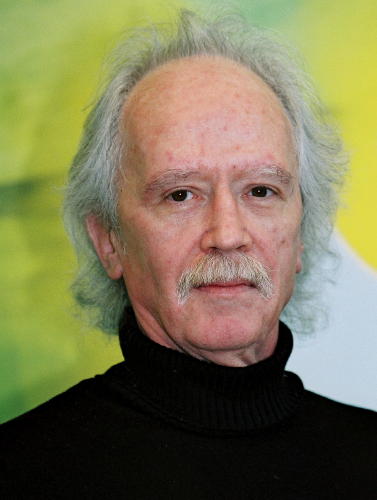

Many of the movie’s fans are riveted by the special effects of Rob Bottin, who was 21 years old when Carpenter hired him. “I didn’t want to see a man in a suit–even Alien, as good as it is, at the end is a man in a suit,” Carpenter said in a later documentary. Using his powerful imagination, Bottin executed drawings and then, pre-CGI, created a series of beings, many of them half-morphed, that are unforgettable. Bottin worked around the clock and at one point had to be hospitalized for exhaustion, pneumonia, and a bleeding ulcer. After The Thing, Bottin, who has been described as a “special effects genius,” worked on films including RoboCop, Total Recall, Seven, and Fight Club.

When The Thing was released, it was not just criticized as nihilistic gore but despised as “instant junk” and “the quintessential moron movie,” with Carpenter viciously attacked, one reviewer saying he was fit for nothing but directing car accidents. Carpenter slid into a depression, by his own account. “I take every failure hard,” he said later. “The one I took the hardest was The Thing.”

Yet critics over the years totally reversed themselves, with one saying, “The Thing is science-fiction/horror with a visionary punch that continues to resonate and inspire filmmakers decades later.” It is now considered a milestone and one of the best science fiction movies ever made. The Thing was a particular influence on the series X-Files.

It took the advent of video and DVD and repeat viewings on television for The Thing to find its way, to build a following, one that is now perfectly prepared to spend time and money to celebrate the artistic achievement of John Carpenter, Rob Bottin, and a group of actors in the subzero temperatures of Outpost 31.

*Correction, Rob Bottin was 21-years-old when Carpenter hired him. We incorrectly stated he was 22. Updated 15th April 2018

Nancy Bilyeau, the U.S. editor of The Vintage News, has written a trilogy of novels set in the court of Henry VIII: ‘The Crown,’ ‘The Chalice,’ and ‘The Tapestry.’ The books are for sale in the U.S., the U.K., and seven other countries. For more information, go to www.nancybilyeau.com.