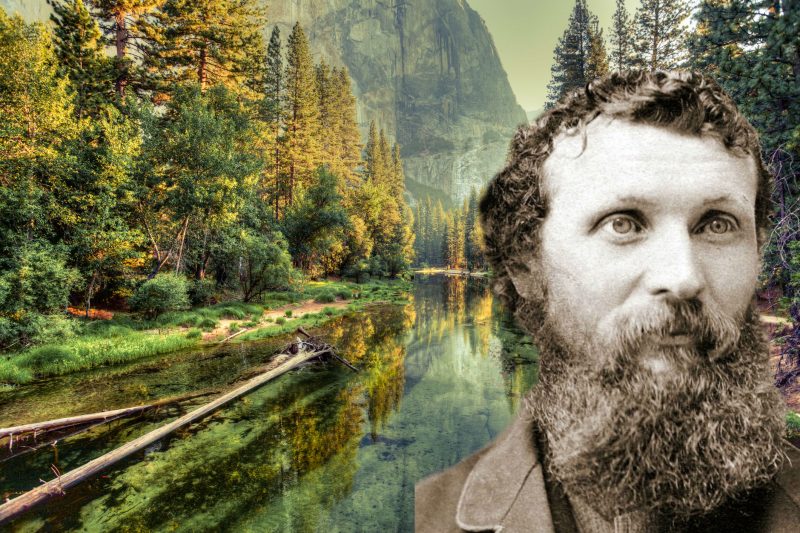

Today the world remembers John Muir as the Father of National Parks, a conservationist who fell in love with the high country of California and ignited passions–including that of President Theodore Roosevelt–to save the most splendid of America’s landscapes. His saying “The mountains are calling and I must go” is commonly seen even today on posters, T-shirts, and bumper stickers.

But long before Muir ever set foot in the West, he set out on a 1,000-mile journey that cemented his love of nature. It was an accident, a simple slip of a file, that triggered that journey from the banks of the Ohio River to the Gulf of Mexico.

Muir, just a young man, had excelled in school and planned to become a doctor, but the Civil War erupted and derailed those plans. Instead, he wandered and worked and eventually landed in a carriage factory in Indianapolis. There Muir was trying to pry off a machine belt with the file when his hand slipped and the file pierced his eye. He was devastated.

“My right eye is gone. Closed forever on God’s beauty!” a co-worker recalled hearing him wail.

He got himself home, lay down, and then–perhaps in a sympathetic reaction–his uninjured left eye also went dark. At least temporarily, he was fully blind. A doctor visited and told him vision in the unharmed left eye would return, and ordered him to rest for a month in a dark room.

But there was little rest. He was tormented by nightmares and misgivings. The only comfort he found was when he remembered his wanderings as a child in the woods, fields and flowers of Wisconsin. Friends, meanwhile, sent for a specialist, who gave Muir good news. His left eye would fully recover and some vision would even return to the injured right eye. When he was able, his former employers offered him another job at a new plant. Muir resigned instead.

He knew the final steps toward healing would come from immersing himself in the world’s natural wonders and he began making plans of his own.

“God has nearly to kill us sometimes, to teach us lessons,” he wrote later. Muir traveled to Louisville, Kentucky, to launch his journey. And if he thought blindness was the closest brush with death he’d have, he was mistaken. Along the way, he ran into highwaymen, hunger, and contracted malaria. And yet there’s little evidence he would have changed a thing.

He made his way through the cave country of western Kentucky to the Cumberland Mountains in Tennessee, where he encountered the highwaymen – believed to be former Civil War guerrillas. But Muir was gaunt, wearing dirty clothes he’d slept in, with scraps of plants he had collected sticking out of his pockets and bags. He hardly looked like a worthy target.

The would-be robbers paused, then turned away on their horses, perhaps believing he was a “poor herb doctor,” Muir surmised in a later account of his travels.

He eventually made his way to Florida and the Cedar Keys, where he was struck with malaria. His treatment was delayed because the mill workers who found him collapsed initially thought he was a passed-out drunkard. The malaria nearly killed him, but finally the fever broke. Recovering, he seemed once again to take on a new sense of joy in his journey.

Related Video:

Of the birds around him, he wrote: “It is delightful to observe the assembling of these feathered people from the woods and reedy isles; herons white as wave-tops, or blue as the sky, winnowing the warm air on wide quiet wing; pelicans coming with baskets to fill, and the multitude of smaller sailors of the air, swift as swallows, gracefully taking their places at Nature’s family table for their daily bread.”

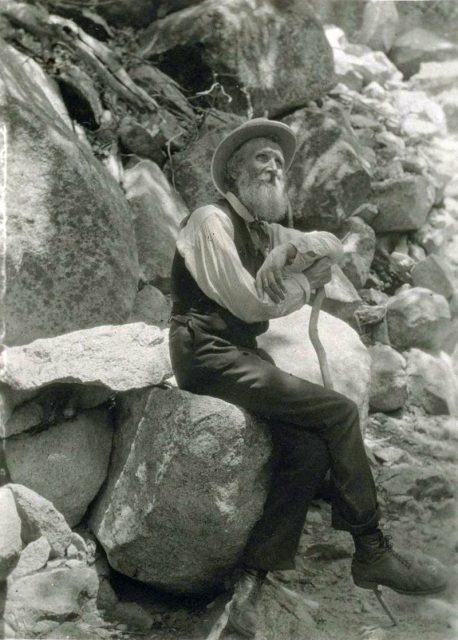

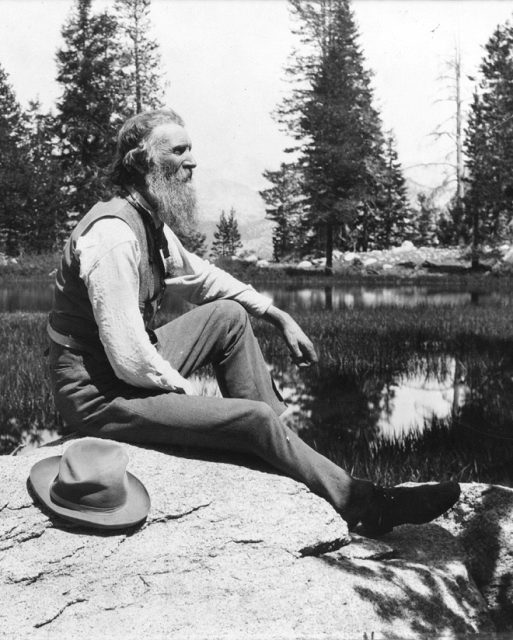

Eventually, Muir found his way to California, where his impact on the country and its resources really began to take shape. He went on to publish 10 books and 300 articles for publications, some in major magazines of the day. Along the way, he befriended other writers, including greats like Mark Twain, Ralph Waldo Emerson, and Rudyard Kipling. He met and was respected by four U.S. presidents, but forged the strongest friendship with Teddy Roosevelt.

Muir practically invented the conservation movement in America, and he was the founder of today’s Sierra Club. His work influenced the creation of Sequoia, Mount Ranier, Grand Canyon, Petrified Forest, and Yosemite national parks.

He lived to be 76 years old, dying in San Francisco in 1914.

Terri Likens‘ byline has appeared in newspapers around the world through The Associated Press. She has also done work for ABCNews, the BBC, and magazines that include High Country News, American Profile, and Plateau Journal. She lives just east of Nashville, Tenn.