“Conduct has been exceedingly bad; he is not to be trusted to do a single thing … [he] has no ambition.” — wrote the headmaster of Ascot prep school for boys in England in 1884 on the report card of a certain 10-year-old disobedient rascal, who was apparently misbehaving and had no future ahead of him whatsoever.

Oh, boy, was he wrong.

Almost six decades later and the boy, now a man in his prime, was appointed as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and entrusted with a task like no other before him in human history.

He was to lead a country and its people in a time of great distress. Europe was overcast by Fascist clouds, France was already under German occupation, and Britain and her Commonwealth was all alone in the fight against the Nazis who were on their way to conquering the continent. It seemed as if there was no way of stopping them. The nation needed a great leader.

They found one in a mischievous boy that proved to be a man of exceptional bravery who in times of great despair displayed unprecedented confidence, rose to the occasion, and rallied his people. Even though the prospect of winning the war at the time was bleak, to say the least, surrender was not an option. Not if he had anything to say about it.

It turned out Sir Winston Churchill had plenty to say and nothing to offer “but blood, toil, tears, and sweat.”

“Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end.” It was June 4, 1940, Churchill was preparing his nation to fight on alone in the war if necessary.

“We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender!”

He never did. Britain never did, and this is perhaps one of the most memorable speeches he gave in his life. One that perfectly captures the relentless spirit, the defiance, and the indomitable will of the “British Bull Dog” as he came to be known.

The people of Great Britain were drawn to him. They looked up to him for reassurance. He was there for his men when they were going through hell to help them keep going and prevail. He was there for the young and innocent at Harrow School a year and a half into the war to remind them that although many had died already, nothing has changed and they should “never give in–never, never, never, never, in nothing great or small, large or petty, never give in except to convictions of honor and good sense.”

Churchill, in fact, was a true Spartan, Britain’s immovable wall. He was their Roaring Lion in the darkest hour. He is now considered to be one of the greatest men that ever lived.

Not because of his tactical decision-making skills that greatly influenced the course of the war. Nor because he was awarded a Noble Prize for literature because of his “mastery of historical and biographical description, as well as for brilliant oratory in defending exalted human values.” He was an influential speaker without a doubt. A voracious reader, prolific writer and a painter in his life outside of politics. But, in the end, the respect he earned had nothing to do with what he was, and everything with who he was. And he was a real piece of character with a hell of an attitude. And “attitude is a little thing that makes a big difference,” according to Churchill himself.

Perhaps that is why he is the most quoted man in existence, right next to Shakespeare, and why one gifted English character actor, renowned for his Method Acting style and a celebrated thespian with a vast experience in both theater and movies, was startled when he took on the challenge to portray a man who according to him was “arguably the greatest Brit who ever lived.”

In an interview with Deadline Hollywood, Gary Oldman talked about the preparation he did to get into character as Churchill. And not just in terms of physique or the 200 hours spent in the make-up chair to become him in Darkest Hour, the film helmed by director Joe Wright that began shooting in November 2016 and was released within a year.

“They’re all challenging in their own way but Winston was kind of a hard one,” said Oldman. “It’s a lot to wrap your arms around. Not only the physical, but he is arguably the greatest Brit who ever lived … a kind of iconic figure. It was daunting but once I started to find out who the man was, it was … well, I never enjoyed anything so much in my life … I couldn’t wait to get to work and be him,” he explained.

The work was indeed daunting, but Gary Oldman mimicked brilliantly a roaring lion untamed on the silver screen and as we all may know by now, deservedly won the Oscar for it. But how? How did he succeed?

By never, never, never giving up and doing exactly what was needed to be done! Or as Churchill said himself, “you must put your head into the lion’s mouth if the performance is to be a success.”

On the question of success, Gary Oldman certainly triumphed, winning the Academy Award for Best Actor this year.

So what did he go through to re-create Churchill?

According to the production team and The Hollywood Reporter, Oldman didn’t literally step into a lion’s mouth of course, but into a 14-pound foam and mattress-padding suit and a silicone face mask. It took around three and a half hours before a scene and almost an hour after to get the actor in and out of Churchill’s “skin,” extending his work hours to 17 hours per day over the course of 48 days. He was unrecognizable; even the movie’s cinematographer, Bruno Delbonnel, was stunned at the sight. “I was searching for Gary Oldman, but the only place I could see him was in the eyes,” he explained for The Hollywood Reporter, adding “it was like seeing Churchill with the eyes of Oldman.”

Credit: Jack English / Focus Features

But the preparation for the man behind that bulky suit took even more energy. Reportedly, the actor among many other things spent countless hours just listening to Churchill’s speeches to learn his vocal tone and speaking rhythm. He spent even more hours watching newsreel footage to understand and master his attitude. And, the most grueling part, he was puffing cigars to the extent that, although he was a true Churchill on the outside, inside he was green as the Grinch. “I got serious nicotine poisoning,” said Oldman.

“You’d have a cigar that was three-quarters smoked and you’d light it up, and then over the course of a couple of takes, it would go down, and then the prop man would replenish me with a new cigar–we were doing that for 10 or 12 takes a scene.” And not just any, but, Romeo y Julieta Cubans, Churchill’s favorites. Approximately 400 cigars, $50 a piece, or $20,000 of the $30 million film budget, literally went up in smoke through Oldman’s mouth. Which understandably was nauseating and excruciating for him, but for the director, it was a sacrifice that just needed to be taken. “It’s Winston Churchill. You can’t have Winston Churchill without a cigar!”

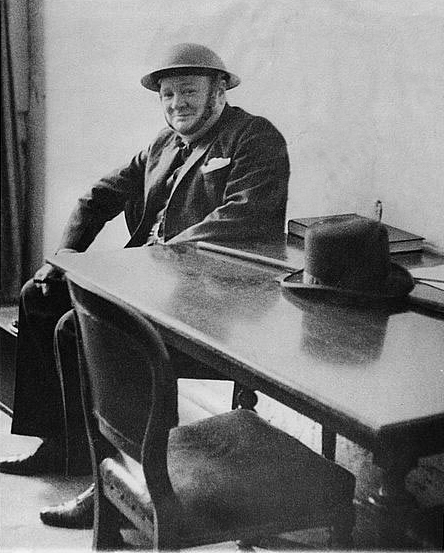

He had a point. Churchill was a notorious smoker and simply loved cigars. He even had a Cuban cigar named in his honor, “The Churchill.” And in that famous portrait of him, The Roaring Lion, that today stands as one of the most widely reproduced images in history? Britain’s great leader is scowling over a lost cigar.

“He was in no mood for portraiture and two minutes were all that he would allow me… Two niggardly minutes in which I must try to put on film a man who had already written or inspired a library of books baffled all his biographers filled the world with his fame, and me, on this occasion, with dread.”

This was how Yousuf Karsh, the iconic portrait photographer, described his first encounter with the British powerhouse and one of the most influential men of the 20th century.

“Churchill’s cigar was ever present. I held out an ashtray, but he would not dispose of it… I waited… Then I stepped toward him and, without premeditation, but ever so respectfully, I said, “Forgive me, sir,” and plucked the cigar out of his mouth. By the time I got back to my camera, he looked so belligerent he could have devoured me. It was at that instant that I took the photograph.”