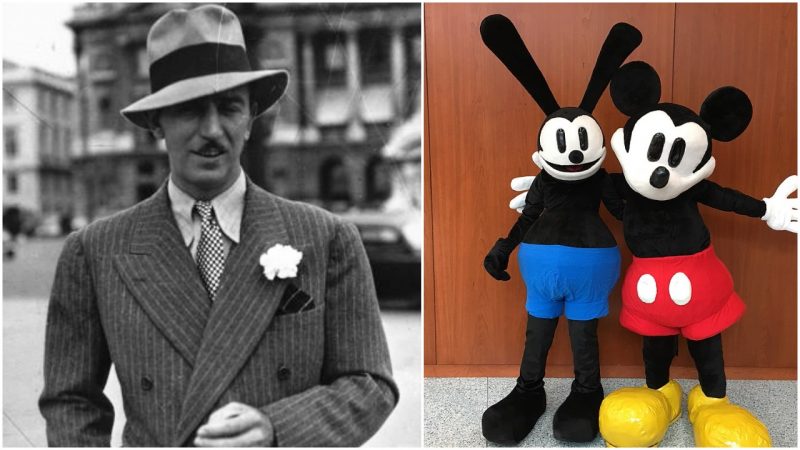

Few figures are more influential in American culture than Walt Disney. His work in the world of animation created films that would speak to the hearts of millions of children and adults worldwide. With his own pluck, determination, and enthusiasm, he built a multi-media empire that remains a major force to be reckoned with, long after his death.

Few people can hear the name Walt Disney without thinking about his most famous creation, Mickey Mouse. Indeed, is there any more iconic American cartoon than the clever, funny, and innovative Mickey? Those three circles put together are immediately recognizable to just about anyone.

Yet, while Mickey Mouse was integral to the success of Walt Disney Studios, the road to his creation was a tumultuous and painful one. It begins with a story of treachery, heartache, and one man’s desire to press forward, regardless of the costs.

In 1923, Walt Disney arrived in Hollywood. Well before the creation of Mickey, Walt was focused on Alice Comedies, a cartoon series starring a real live girl who would go on various adventures in an animated world. His previous studio, Laugh-O-Gram, back in Kansas City, had failed due to the high cost of production for animation, and Walt hoped that things would fare better in California. His brother, Roy, would join him in his venture and the two would start their next studio, Disney Brother’s Cartoon Studio.

Armed with the reel from the first Alice Comedy, Alice’s Wonderland, Disney was able to secure a distribution deal with Winkler Pictures, run by Margaret Winkler and her fiancée, Charles Mintz. The deal was relatively simple: Disney would produce six more Alice pictures and Winkler Pictures would pay a modest sum for each short. This would give Walt and Roy the means to continue expanding their own studio. Soon, in 1924, they would be able to hire Ubbe Iwerks, Walt’s old animating partner from the previous studio and persuade him to join the studio in California.

More contracts came down the pipeline to Disney from Winkler Pictures, yet a shift in management would prove hazardous to Walt. Margaret Winkler married her fiancée and soon became pregnant, leaving her husband to run the distribution company. Charles Mintz was an aggressive and hard man, who pushed Disney to constantly produce high quality (and cheaper) works that would eventually end up taking a toll on Disney’s entire studio. The Alice Comedies had a decent run, but by 1927, Disney was ready to take on something new.

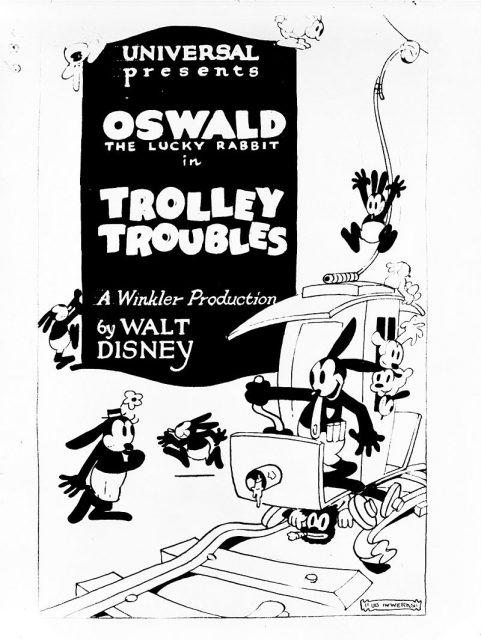

Mintz, as it turned out, was in talks with Universal Pictures to provide them with a brand-new cartoon series. Walt was asked to provide something that would satisfy Universal, and soon Iwerks and Walt would come up with Oswald the Lucky Rabbit. This large, bounding rabbit with tall ears and a big grin was quick to gain acclaim and Oswald was a hit with both Universal and the public.

Yet, despite Disney’s success with the creation of Oswald, Charles Mintz grew weary of his relationship with Walt. In his eyes, Oswald’s success was due to the work of Ubbe Iwerks and the rest of the studio as opposed to anything Walt provided. Walt, more or less, seemed to be expendable. Mintz began to steal Walt’s employees away from his own studio, offering them contracts behind his back. When Oswald’s picture contract with Universal was up, Charles Mintz negotiated another deal with them, extending the contract for the period of three years, without Disney’s knowledge. The rights to Oswald, after all, were in the hands of Mintz, not Walt.

Worse yet, when Walt went to meet with Mintz in order to negotiate for his contract in order to get more pay, Mintz made him an offer that infuriated Walt. Mintz offered him a 50/50 split of the profits made from Oswald, a reduced rate of pay for production costs as well as options for Walt to take a salary from Mintz. In other words, Mintz wanted Walt to work for him.

This would not do for Walt. He refused such a deal and stormed out, hoping that his employees would be loyal to him, aware that Mintz had sniped most of them from behind his back. The combined pressure from Mintz and Walt’s inexperience with management had led to serious tension between him and his staff back at the studio, making it easy for Mintz to lure them away, leaving Disney with only a few employees left. For the second time in his life, Walt would find himself starting over again. With only a few team members left and a scant amount of money, as well as a contractual obligation to work on Oswald cartoons, Walt was at one of the lowest points in his life.

Yet, it would be from these ashes that Mickey Mouse would rise. Walt, desperate for some cartoon idea that would catch fire, worked closely with Ubbe Iwerks. Together, they came up with the idea of a mouse character, with Ubbe drawing the model for the mouse that we all love today. Mickey Mouse would go on to debut in two shorts, Plane Crazy and The Gallopin’ Gaucho, but neither film was picked up by distributors.

At this time, the live action film The Jazz Singer had just released, complete with synchronized sound, speech, and music; a groundbreaking work of art that would revolutionize the film industry as a whole. Walt, having seen this film, realized that synchronized sound would be the ticket to bringing Mickey’s personality to full realization. In 1928, he and his small team worked valiantly to create Steamboat Willie, the now-iconic Mickey Mouse cartoon that is most popularly believed to be the first Mickey cartoon. Steamboat Willie was not the first cartoon with sound, however it was the first Disney cartoon that had perfect synchronization, with music and sound effects that lined up with each action.

Steamboat Willie was a critical success. The comedy, the music, and the brash, bold, and mischievous character of Mickey captured the hearts of the audiences everywhere. Steamboat Willie, for all its simplicity, would be hailed as a milestone in Disney’s career. The road to true success for Disney would still be a way off, but he was able to move past one of his greatest encounters with failure, the loss of his animators and the treachery of Mintz. He would go on to grow both the Disney and Mickey brands, setting the wheels in motion to turn Disney Studios into the company that it is today.

Andrew Pourciaux is a novelist hailing from sunny Sarasota, Florida, where he spends the majority of his time writing and podcasting.