If there was one thing that King Richard I, known as Richard the Lionheart, had in abundance, it was enemies.

In April 1199, the French King, Philip II, thanked God for the providential death of his great rival, Richard. Ever since the English king was freed from his prison in Austria in 1194, he had turned his war machine on the French, reclaiming the lands and castles that were taken while he was captive. Had he continued his relentless campaign, Richard might well have conquered the whole of France, and medieval history would have turned out quite differently.

But at the age of 42, Richard died. He was slain during a siege of a small and seemingly unimportant French castle, and certain aspects of his death struck the chroniclers of his time–and later historians–as strange, almost sordid. It was an anticlimactic end to the life of the Lionheart.

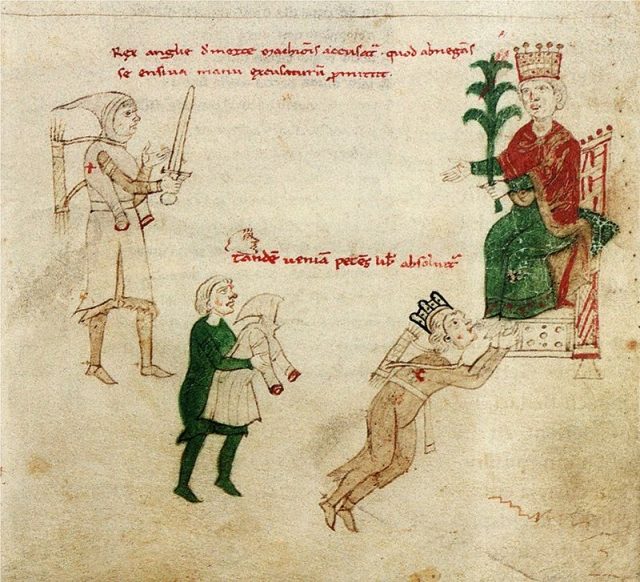

Richard was taken captive on his way back from the Third Crusade. Leopold of Austria held grudges against Richard, and he put him in a secret prison. Once Queen Eleanor, Richard’s mother, discovered where her beloved son was, she appealed to the Pope. The Holy Roman Emperor set a ransom of 150,000 marks–65,000 pounds of silver. It was an astronomical sum, estimated to be three times the annual income of the English crown. But Eleanor raised it.

In the legends of Robin Hood, Richard is a benevolent ruler, who after being freed forgives his brother John and returns to the task of governing England. But Richard had little interest in England his whole life–he is rumored to have said, “If I could have found a buyer, I would have sold London itself”–and was passionate about going on Crusades or fighting for more French territory than he already possessed as the ruler of the Aquitaine.

Richard decided what he needed was an impregnable castle from which to defend Normandy and then retake critical French land. The vast one that he built required two years of punishing around-the-clock labor and cost an estimated £20,000, more than had been spent on any English castle in the last decade. Legend has it that while building the Chateau-Gaillard, Richard and his men were drenched with “rain of blood,” but he refused to take it as an evil omen.

In March 1199, Richard was in the Limousin, suppressing a revolt by the Viscount of Limoges. He “devastated the Viscount’s land with fire and sword.” Then he besieged the nearby small chateau of Chalus-Chabrol. Accounts differ on why; some say it was because a peasant found treasure underground–either Roman gold or valuable objects–and Richard was so desperate for money, he lay siege to the castle. But some historians say that this entire area was of strategic importance to Richard’s hold on France, and he was only there to suppress rebellion.

What most historians agree on is that Richard was walking the chateau’s perimeter without wearing his chain mail and he was shot by a castle defender using a crossbow. The wound in his left shoulder turned gangrenous. It steadily grew worse over the next 10 days. Some wrote that while dying Richard asked that the bowman be brought to him. He then forgave the man, who was named Peter Basil, and instructed that he should not be harmed. Richard died in the arms of his mother on April 6th, historians say. Later, defying Richard’s orders, Peter Basil was flayed alive and hanged.

Why did Richard I, a seasoned and expert warrior, expose himself to a bowman’s shot? Did the king and crusader put his life at risk to claim some grubby treasure dug up from the ground?

Following the custom of the time, Richard’s body was buried in different places. His heart was buried at Rouen in Normandy; his entrails in Chalus; and the rest of his body near his father’s remains in Anjou.

Several years ago, a French forensics expert received permission to analyze a small sample of Richard I’s heart to determine if the cause of the king’s death was indeed septicemia, an infection of the blood. All that was left of it was dried remains, not enough to definitely confirm septicemia. They did detect bacteria but no arsenic or other sources of poison, ruling out an arrow dipped in poison, which was rumored for a while. No one could accept the fact that an ordinary arrow killed the Lionheart.

What the scientists also discovered was that the king’s heart was embalmed using materials more akin to the practices of the ancient world than medieval Christian society. According to Scientific American: “Elemental analysis turned up high concentrations of calcium, suggesting that lime may have been used as a preservative. Mass spectrometry identified organic molecules characteristic of creosote and frankincense, both used for preserving tissue.” Moreover: “It proves that embalming of Christians did happen,” Stephen Buckley, an archaeological chemist at the University of York, UK, who has conducted forensic analyses of Egyptian mummies, was quoted as saying. “The Church has tried to downplay the use of embalming in religious leaders and royalty” in the past because of the pagan origins of the practice, he adds.

However, there is another explanation. Experts speculate that in 1199, when embalming Richard’s heart, they were actually trying to replicate the process used in the time of Jesus Christ. This gives another clue as to how Richard was viewed in his lifetime. Dr Philippe Charlier, a forensic scientist from Raymond Poincare University Hospital, in France, told the BBC: “The spices and vegetables used for the embalming process were directly inspired by the ones used for the embalming of Christ. For example, we found frankincense. This is the only case known of using frankincense–we have never found any use of this before. This product is really devoted to very, very important persons in history.”

The scientific team that performed the test concluded: “We found that the heart was deposed in linen, associated with myrtle, daisy, mint, frankincense, creosote, mercury and, possibly, lime. Furthermore, the goal of using such preservation materials was to allow long-term conservation of the tissues, and good-smelling similar to the one of the Christ (comparable to the odor of sanctity).”

Related story from us: Sherwood Forest: A place for not only Robin Hood but also the Vikings

Something odd did surface in the testing: Scanning electron microscopy identified pollen grains from myrtle, mint, and other known embalming plants, as well as poplar and bellflower. These plants could not have been all in bloom when Richard is said to have died, April 6th. It is weeks too early. Late May is when this level of pollen would have been reached. Yet chroniclers are firm on the early April date.

And so mysteries deepen in the death of the king.

Nancy Bilyeau, the U.S. editor of The Vintage News, has written a trilogy of novels set in the court of Henry VIII: ‘The Crown,’ ‘The Chalice,’ and ‘The Tapestry.’ The books are for sale in the U.S., the U.K., and seven other countries. For more information, go to www.nancybilyeau.com.