In August 2017 a group of angry protesters and human-rights activists gathered around the statue of Dr. J. Marion Sims in Central Park in New York City.

Fired up, enraged, dressed in white hospital gowns sprayed with red (as in blood) to signify women’s pain and suffering during and after surgeries, they were demanding the man’s statue be removed.

Simultaneously, another group was asking the same in Columbia, South Carolina, Sims’ birth state and where the state health department is also named in his honor. In fact, activists have been working for a while now to remove his statues and his name from everything that celebrates his achievements.

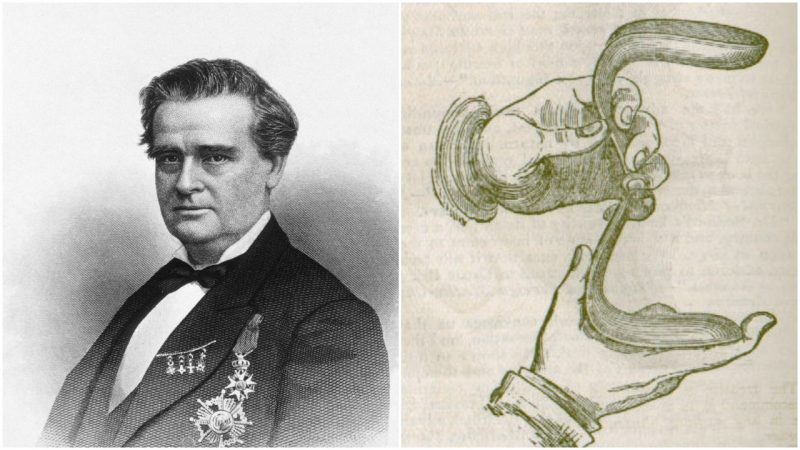

This 19th-century doctor, dubbed the “father of modern gynecology” and inventor of the speculum, is lauded as a true pioneer in the field of surgery. He stands as the first person to successfully perform gallbladder surgery, and he developed a groundbreaking technique to treat women with vesicovaginal fistula. This is a painful and extremely unpleasant tear between the uterus and bladder that can occur as a severe complication of childbirth, resulting in constant urine leakage from the vagina and lifelong suffering. He also treated rectovaginal fistulae, or vaginal tears that allow waste products to exit from where they should never come out under normal circumstances. Sims treated delicate matters in times when the fledgling field of gynecology was viewed by many as immoral because it involved the hands-on study of women’s “personal” anatomy. He founded the first hospital for women in the U.S. in 1855 and set up an exclusive private clinic in his later years.

Why the protests? The problem, according to his critics, was that he was allegedly neither skilled nor trained in gynecological practice when he started out as a surgeon. By his own admission, his pathway into gynecology was, quite literally, accidental. However, no-one before him had been successful in treating the devastating conditions that Sims figured out a way to treat, and became determined to do so. The controversy surrounding this pioneering doctor is one of ethics: That while honing his skills, he is accused of not treating the delicate delicately enough, and of being racially biased in his administration of anesthetic.

According records of medical history, this is likely to have been because the only available methods of anesthesia at the start of his career were themselves dubious. Sims’ records indicate that he adhered to the accepted common procedure of supplying pain relief in the form of opium post-operatively to his patients.

Sims was born on January 25, 1813, in times when becoming a doctor did not involve rigorous courses like there are today, nor there was a long specialized training needed to go through before practicing medicine on humans. After graduating from South Carolina College, aged 21, he interned with the county’s only physician for a while, whose daughter he subsequently married.

After completing a three-month course at Charleston Medical College, he went on to study at the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia for a further year (1834-5). He was now a qualified doctor.

It was a poor start as his first two patients died after Sims treated them. Sims and his wife quietly left Lancaster Village where he had set up practice, moving to Montgomery, Alabama, and started fresh.

And it was there, in the 1840s, he had the “most memorable time” of his life as a doctor. He was employed by white and wealthy plantation owners as physician to their slaves. A doctor was a good investment to the plantation owners; if the slaves could not work, they were of little to no use for their masters. And women with long-lasting childbirth complications might be debilitated for the rest of their lives.

Before the advent of modern healthcare as we know it, childbirth was a dangerous affair, with high mortality rates and a shocking amount of postpartum physical complications. Vesicovaginal fistulae were commonly caused by prolonged obstructed labor. Generally baby died in these cases and mom’s chances weren’t great either–no emergency C-section for women back then. If she survived, her body would be a wreck.

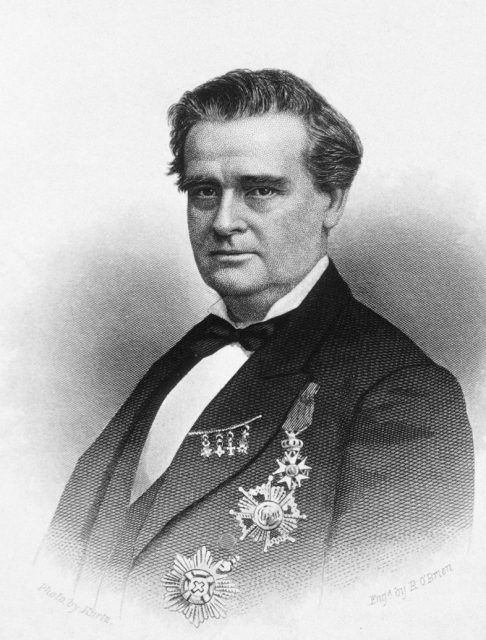

According to his autobiography, The Story of My Life, Dr. Sims was one of three doctors attending plantation workers in the area. He mentions that, initially, when slave-women asked to discuss any “functional derangement of the uterine system, I immediately replied, this is out of my line.” However, his remarkable contribution to medicine was inspired when treating the pelvic injuries of a woman who had fallen from her horse. Setting her in an appropriate position, he was able to see a way to access her vagina with his new speculum invention, which, he realized, would allow him to repair a fistula.

Now he wanted to see if he could do it in practice. From 1845 to 1849, Sims conducted experimental surgery on what was considered to be an incurable condition, at his small backyard hospital. His subjects would be the enslaved African-Americans who were already under his medical care. “There was never a time that I could not, at any day, have had a subject for operation,” he recalled.

In an era when observing surgery was part of medical training (in the “operating theater”), it was natural for Sims to invite all the local doctors to witness his first attempt at a new technique. “Lucy’s agony was extreme,” he wrote in his notes about one 18-year-old patient. For months she had been in pain and was constantly leaking urine after an extended traumatic labor and stillbirth. Her owners brought her for treatment and Sims took her in.

The operation lasted for an hour, during which time Lucy was down on all fours with her head resting on her arms as 12 other doctors carefully watched Sims do the procedure. She contracted blood poisoning due to his leaving a sponge inside her, which was supposed to help drain the urine. “I thought she was going to die…it took Lucy two or three months to recover entirely from the effects of the operation,” he wrote. Despite the setbacks, Lucy was his first success.

The slave-owners were more than willing to consent to their fistula-suffering ladies being subjects in Sims’ trials, as perhaps they could finally be to put back to work afterward. Writing in the Journal of Medical Ethics, Durrenda Ojanuga gave the opinion that “The enslaved women were not asked if they would agree to such an operation.” It is her paper, published in 1993, that seems to have stirred up the recent wave of hatred towards L. Marion Sims.

But according to an article in the New York Medical Gazette and Journal of Health of January 1855, Sims wrote he was “agreeing to perform no operation without the full consent of the patients, and never to perform any that would, in my judgment, jeopardize life, or produce greater mischief on the injured organs.” In fact, L. L. Wall postulates in his research paper, “The medical ethics of Dr J Marion Sims: a fresh look at the historical record,” published in 2006, also in the Journal of Medical Ethics, that the surgery would not have been possible without the cooperation of the patient. Wall also cites sources, including accounts by surgeons, to counter Ojunaga’s implication that “it would never have been appropriate for slaves to undergo innovative [therapeutic] surgical operations.”

Today’s critics of Sims do question his ethics, saying that he was taking advantage of the slave system to perform experiments on human beings, rather than taking care of them. According to them, he experimented on slaves who simply couldn’t say no and, even worse, without anesthesia because of a popular but false belief of the 19th century that the black slaves didn’t feel pain. After he had perfected the methods, he later operated on white women, but, the critics say, with them he used ether as an anesthetic.

It should be noted, however, that the effects of ether were first publicly demonstrated on October 16, 1846, and that free white people were also operated on under the same condition. There was no such thing as safe drug trials in 1846, so getting the dosage right was a matter of trial, error, and hoping for the best. According to historian Martin Pernick, “highly reputable practitioners and ordinary lay people held many misgivings about the new discovery.” Doctors were still testing its efficacy as late as 1849 by performing comparative operations with and without the administration of ether, as described by Crawford Long in December of that year, in the Southern Medical and Surgical Journal.

Kelly M. Hoffman, Sophie Trawalter, Jordan R. Axt, and M. Norman Oliver concluded in their 2016 research paper “Racial bias in pain assessment and treatment recommendations, and false beliefs about biological differences between blacks and whites,” published in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, that “people assume a priori that blacks feel less pain than do whites,” and that racial bias exists in the modern U.S. healthcare system, which they attribute to historic stereotyping.

The study cites sources which discuss the widely posited supposition in the 19th century of physiological differences between people of different skin color: “these beliefs were championed by scientists, physicians, and slave owners alike to justify slavery and the inhumane treatment of black men and women in medical research.” For instance, Dr. Samuel Cartright is quoted as writing of a “Negro disease [making them] insensible to pain when subjected to punishment,” while others apparently held an opinion that blacks could undergo a surgical operation with little, if any, pain at all.

Second in line for Dr. Sims’ fistula repair trial was 17-year-old Anarcha. He operated repeatedly on her, 13 times over four years, no anesthetic, slowly improving the design of his tools and technique. Success came on June 21, 1849, with the application of silver-wire sutures. So it’s not so odd why some would assume that she was his test subject and he was experimenting on her, perfecting the methods which he put into practice a couple years later in New York.

Not all of his patients had Lucy’s luck or Anarcha’s perseverance–some died, some couldn’t endure the procedure. Sims recorded conducting experimental surgery on 12 enslaved African-American women between 1845 and 1849. He performed operations on even more when he moved to New York, as well as a growing number of middle and upper-class white women. Reportedly, at a public lecture in 1857, he declared it was not worth the trouble or the risk to anesthetize his fistula patients. It’s a statement that would have been much less controversial at the time than it might be considered today.

“At best, he was a man who recognized the humanity of black slaves to use them for medical research about the human body—but not enough to recognize and treat their pain during surgery. At worst, J. Marion Sims was a racist man who exploited the institution of racism for his own gain,” declared Seshat Mack in August 2017 in the New York Daily News. From the modern vantage point, it is easy to criticize the ethics and morals of those in past centuries.

Sims’ statue was removed from Central Park on April 17, 2018, and as it is believed it will be transferred to Greenwood Cemetery in Brooklyn.