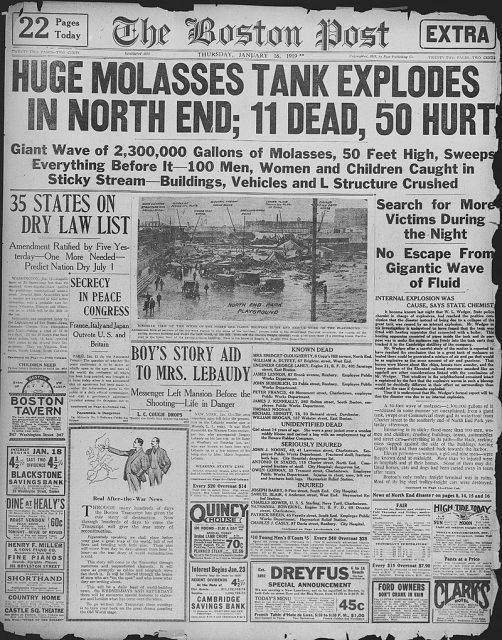

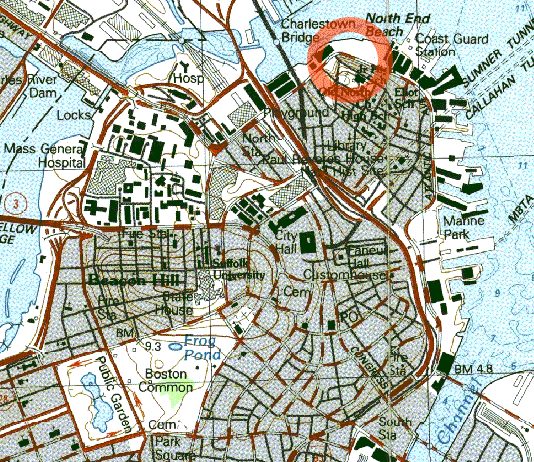

“The Great Molasses Flood.” At first, it sounds surreal—maybe even a little comical. But there was nothing funny about an event that took place almost a century ago on the streets of Boston. On January 15, 1919, the city suffered through one of the strangest disasters in history: a tidal wave of molasses which tore through the city’s North End, toppling buildings, trapping people and animals, and leaving utter devastation in its wake.

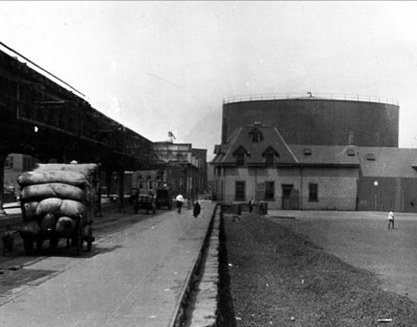

Most of us think of molasses as a super-sweet ingredient used in pie and cookie recipes, but the sticky stuff can be fermented and employed in other ways. United States Industrial Alcohol, which got regular shipments of molasses from the Caribbean, used it to make alcohol for liquor and the manufacturing of military equipment. (In fact, the company built a massive steel storage tank four years earlier, when World War I increased the demand for industrial alcohol.)

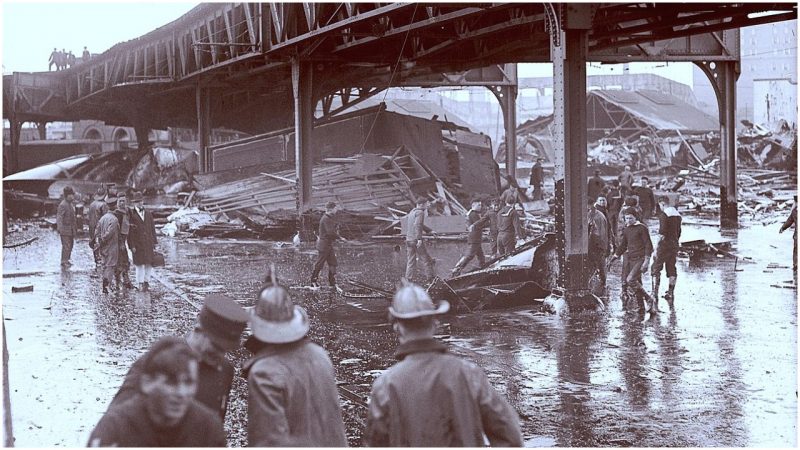

Measuring 50 feet tall and 90 feet across, the tank was capable of holding 2.5 million gallons of molasses. But just after noon, on the 15th, something went terribly wrong. The tank’s rivets popped, and the steel sides burst open. Suddenly, 26 million pounds of molasses, traveling at a speed of 35 miles an hour, tore down the streets of the city’s North End—a 15-foot wave, destroying everything in its path. It snapped the support girders from an elevated train track, brought down electrical poles, and tore houses from their foundations, demolishing them. In all, the wave had caused damage worth $100 million in today’s money.

Many of those who found themselves in the path of the flood drowned or were crushed in the gummy wave. A Boston Post account described the carnage: “Here and there struggled a form—whether it was animal or human being was impossible to tell. Only an upheaval, a thrashing about in the sticky mass … Horses died like so many flies on sticky fly-paper. The more they struggled, the deeper in the mess they were ensnared. Human beings—men and women—suffered likewise.”

The flood would claim 21 lives. Rescue attempts were tricky. To reach the victims, medics and police officers had to struggle mightily through the thick, waist-deep muck. Another challenge to overcome: ridding the streets of two million gallons of molasses. Firefighters quickly discovered that their hoses, blasting fresh water, were useless against the hardened mess. Saltwater proved a more effective way to wash the goo into gutters. However, because of the scores of people plodding through the muck and dispersing the sticky mess (via their bottom of their shoes) throughout the city, the sickeningly sweet smell would linger on for years afterwards, a macabre reminder of the tragedy.

Waves Flood Harbor of Town in Azores During Storm

In the meantime, United States Industrial Alcohol Company was feeling the heat. In an effort to absolve itself of any blame, the company claimed that anarchists had sabotaged the tank, pointing out that alcohol was an ingredient in military equipment. Another theory floating around: The explosion was caused by the fermentation process inside the tank.

But investigators weren’t buying either explanation. After digging around, they determined that the reason for the wreckage was slipshod construction work.

The company, wanting the tank built quickly and cheaply, cut corners, making the steel walls too thin and fragile to withstand the 20-plus million gallons of molasses. What’s more, the company never bothered to bring in an engineer to oversee the project. But perhaps the most jaw-dropping bit of information: Residents reported that when the tank started leaking during its construction, USIA got crafty, painting the tank brown to mask the openings.

What followed was a doozy of a long, drawn-out legal battle, lasting six years. USIA faced 125 lawsuits, most from North End residents. After hearing thousands of hours of testimony, Colonel Hugh Ogden, appointed auditor by the state superior court, eventually filed a report citing a reckless disregard for safety in the tank’s construction as the cause of the disaster.

The company was ordered to pay approximately $7,000 in restitution to the family of each victim.

There was some good to come out of the calamity: People become more aware of the devastating effects that came from cutting corners in construction. What’s more, the tragedy led to many states—Massachusetts among them—enacting laws requiring engineers and architects to be consulted on major construction projects.

Barbara Stepko is a New Jersey-based freelance editor and writer who has contributed to AARP magazine and the Wall Street Journal.