The end of the world has been foreseen numerous times in history and has sometimes caused global panic as superstition took hold over large groups of people. Some of these stories are intertwined with religious cults that have in one way or another used their followers’ beliefs in setting their agenda of the end of the world.

In other cases, doomsday has taken on a pseudo-scientific background, like the Millennium Bug or the more recent 2012 phenomenon.

This craze dates way back. Especially when it comes to religion.

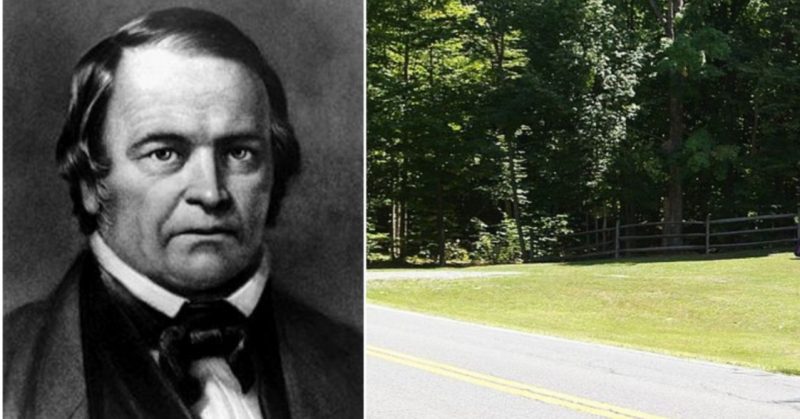

One such case traces to March 21, 1844. This date was predicted to be the Second Coming of Christ by a Baptist preacher who decided to offer his own interpretation of the Bible, and while doing so, amassed a number of followers in mid-19th century United States.

His name was William Miller, while the people who were initiated into the religion of his making were called Millerites. Miller’s legacy is the root of today’s Advent Christians, the Seventh-day Adventists, and other Adventist movements.

Before becoming a religious figure, William Miller was a participant in the War of 1812, when the United States Army battled Great Britain, which was in a larger context part of the Napoleonic Wars in Europe.

Having survived a near-death experience at the Battle of Plattsburgh in 1814, William felt the need to rethink his Baptist faith, which promoted God as a Supreme Being, distant from human affairs.

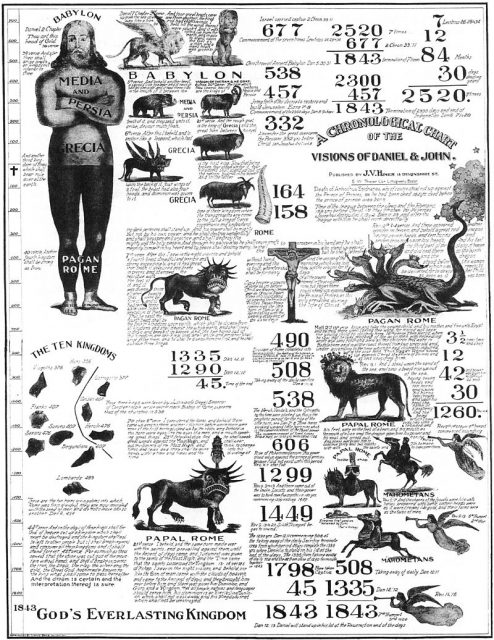

What he saw as an intervention of God’s will soon become the basis of his own theology. Following a period of studying the Holy Word, he concluded that the Second Coming of Christ was imminent and that it would bring with it the end of the world in the form of a battle of good versus evil. Miller’s musings were largely based on Daniel 8:14: “Unto two thousand and three hundred days; then shall the sanctuary be cleansed,” which he took as meaning the cleansing of the earth by fire.

Of course the good will be rewarded with eternal life, while the bad would―well you know―burn in hell.

Miller did not set a precise date; his calculations, based on the Karaite Jewish calendar, set the Second Coming as “sometime between March 21, 1843, and March 21, 1844.” But when the world went on as normal that day, Miller declared a new date of April 18, 1844, which also turned out to be just another day. Following close scrutiny of the Old Testament at a camp-meeting that August, it was the turn of Samuel S. Snow to propose the actual date that the world should expect its fiery judgment. October 22, 1844, or the Great Disappointment, did not herald the Second Advent. Many of the Millerites, more than 50,000 of them, abandoned their belief in Miller’s preaching.

Some of them, however, perceived this as a mere miscalculation and felt it was necessary to go back to the source for further instruction. The leader of this branch was called Peter Armstrong, and what followed was a rather literal interpretation of Isaiah 40:3: “A voice of one calling in the wilderness: ‘Prepare the way for the Lord’ ”

Armstrong assembled what was the rest of the Millerites and bought a piece of land in Sullivan County, Pennsylvania, where he intended to create the “the new Zion” on Earth.

Armstrong had certainly found his wilderness―181 acres of it. But he still needed to attract more followers who would inhabit his self-proclaimed paradise on Earth in an effort to achieve the purification from sin which would lead to the Second Coming of Christ.

The zealous Armstrong continued purchasing land, amassing around 600 acres, which was more than enough to fit a small town in.

This was how Celestia was founded in 1850.

The community published their local newspapers, called The Day Star of Zion and Banner of Life, and built houses while selling land parcels for just $10 each. Around 300 such lots were sold to the believers, as the community in the wilderness turned into a vibrant town.

Mysterious ancient societies that historians know almost nothing about.

They advocated a “life without seeing death and corruption,” together with teachings of how to organize a “Divine Communism of ‘Faith, Love and Purity,’ ” and to overcome “the nature of man” while perceiving “what he loses through Adam, and what he gains through Christ.”

The land itself was deeded to “Almighty God, who inhabiteth Eternity, and His heirs in Jesus Messiah,” thus making it God’s own property.

As the years passed, the community grew, but so did turmoil in the United States. When this turmoil reached a boiling point and the Civil War broke out, draft notices came addressed to the residents of Celestia.

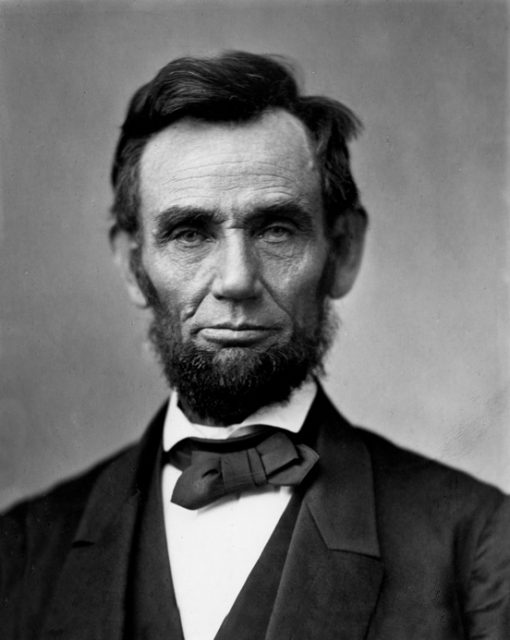

Since the community strongly opposed violence, Armstrong wrote to President Lincoln, asking him to exclude the settlers of Celestia from the draft.

Lincoln agreed, and his decision was interpreted as an act of God by the Millerites, but actually, it was quite the opposite. As news of the people of Celestia being protected from the draft reached other parts of the country, a number of people avoiding military service hurried to the 600-acre religious commune.

At first, this too was seen as a good thing, but it soon became apparent that none of the newcomers were actually interested into the teachings of William Miller and his disciple Peter Armstrong.

This large influx of draft-dodgers affected life within the commune. Very soon Celestia started looking more like a regular midwestern town, and not at all like a strict religious commune awaiting the Apocalypse.

Disappointed, Armstrong finally decided to abandon the town he had created. He moved to Glen Sharon, also in Sullivan County, in 1872, where he and his most loyal disciples were hoping to start anew.

Unfortunately for them, the community was never resurrected, and the last attempt of Armstrong’s believers to welcome Christ by living the life they perceived to be suitable for reaching heaven came to an end.

As for Celestia, it was auctioned by the Sullivan County government in 1976. When Armstrong deeded the land as God’s property, he believed that the act would allow him and his followers to become immune to taxes, for he expected the authorities to perceive Celestia the same way he did―as sacred.

But the county government forced Armstrong to sell the land in order to retroactively pay his property taxes. It was settled when Armstrong’s son bought the land from his father, in order to keep it in the family, but the dream was over.

It was no longer the meeting ground for pilgrims and settlers who firmly believed in the Second Coming of Christ, nor was it a safe haven for draft dodgers as the war ended a decade before.

It was just a ghost town with a few inhabitants who saw it as the only home they had. Peter Armstrong and his family, together with some others, continued living in Celestia, but even to them, it was clear that the Celestial Religious Community would never regain its former glory and that Doomsday may have been postponed indefinitely.

Nikola Budanovic is a freelance journalist who has worked for various media outlets such as Vice, War History Online, The Vintage News, and Taste of Cinema. He mostly writes about subjects such as military history and history in general, literature, and film.