One day in 1651, Dutchman Joannes Lethaeus, better known to the world as Jan de Doot, reportedly told his spouse to go the fish market and then called his brother for a little assistance over a private matter. Certainly, he would have a lot to explain to his wife later when she came back home from the market, because, in the meantime, he planned to performed surgery on himself. Little or big, surgeries are a serious thing.

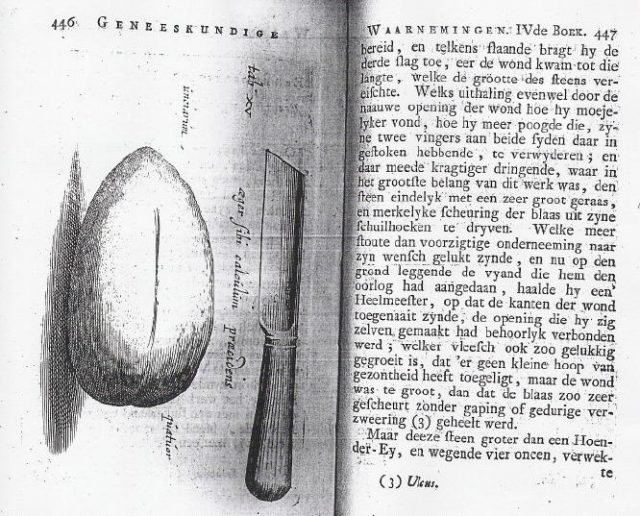

He was to cut into his body to release a stone that obstructed his bladder. This obscure case of self-surgery has been documented in a book called Observationes Medicae, by Nicolaes Tulp, who was a physician himself and also served as the Mayor of Amsterdam in the 17th century. The book was published in 1672 and documents over 200 medical cases.

Jan de Doot, by occupation a blacksmith, had already faced problems with bladder stones before moving on to perform the gruesome act. Twice he had been cut by people trained to do exactly that–remove stones from people’s bodies. Given that even the most mundane of surgeries in the 17th century would not have been by any imagination as painless as modern-day utilities allow, the previous experiences must have been traumatic for the Dutchman. For the new bladder stone, he decided it would be only he alone to wound and tear his flesh, a step that definitely took unprecedented courage.

So, while his spouse was out and about, his brother arrived and was instructed to hold his scrotum on the side so that Jan de Doot could precisely locate the prominent stone with one of his hands. He then used the other hand to make a cut in the perineum, after which he squatted down a couple of times to expand the wound just enough to make room for the invader to come out. This is horrid: he then allegedly placed his fingers in the open wound and reached for the bladder stone to finally lever it out.

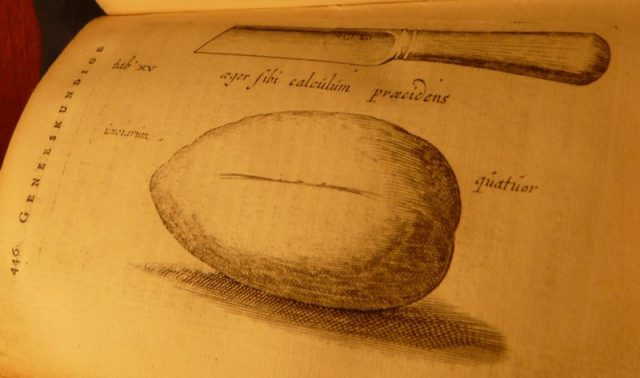

In the process, Jan de Doot may have damaged his bladder too, but the stone–weighing some four ounces and the size of a chicken egg–was out. Only at this moment did Jan de Doot ask his brother to fetch a healer to stitch him back up. It seems that the self-surgery was a success and it is assumed the self-treating patient recovered and lived at least five more years after this radical approach to healing.

Of course, after this event, the story spread and people were fascinated that someone had managed to take out their bladder stone on their own. But those more knowledgeable in medicine shared their thoughts that it was very strange how Jan de Doot performed a lithotomy procedure without appropriate medical instruments and the use of a single hand only.

Even later contemplation on the case by experts, as of the 20th century, agree that it would not have been that easy for the stone to come out as the Dutchman reportedly explained. As HistoryCollection.co writes, it is probable that the stone might have moved through the body because of the previous slits made to extract the first two stones that formed in Jan de Doot’s body. That somehow, this third stone ended up in the immediate subcutaneous tissue–meaning just underneath the skin. This would explain, it is reported, how De Doot could have performed the self-surgery with such “ease.”

Weighing in at four ounces, Jan de Doot indeed coped with the prominent stone. It is likely that it had formed due to a more serious inflammation caused by a chronic infection in the urinary tract, or perhaps it was problems with the prostate that made him suffer.

Whatever the case, there is one artwork that immortalizes Jan de Doot and his great feat of courage. A portrait of him, where he holds the stone, toned in gold, as well as the knife he used for the effort, was painted in 1655 by Antwerp-born Carel van Savoyen. The work is now accommodated at the University of Leiden in the Netherlands.

As to the question of whether Jan de Doot is the sole case of someone performing self-surgery, he is not. People have subjected themselves to the unthinkable many a time when in urgent need, such as in the more recent case of Aron Ralston, who made news in 2003.

Ralston was on a solo-trip in Blue John Canyon–a remote slot canyon in Utah’s Canyonlands National Park–when an 800-pound boulder fell, trapping his right forearm against the canyon wall. Five days later, still stuck, utterly wasted and without success to free his arm from the boulder, the outdoorsman decided that to amputate his already decaying arm was his only chance of survival. He did survive the event.

There are but a few more cases when people have made drastic moves for the sake of their health or guided by their survival instinct. And as Observationes Medicae further remarks on Jan de Doot’s case, “sometimes daring helps when reason doesn’t.”