During the Blitz, the whole of Britain was on a need-to-know basis. Newspapers were censored until they were cut to just a few pages, delivering news that was only stating the obvious without providing any information that could potentially be used by the enemy.

Photographs of bombed buildings rarely reached the front pages, as the government feared that the sight of destruction could serve as a serious blow to the morale of the people. It was the same for the articles.

Although wartime censorship affected almost all aspects of the media, one ingredient of a successful paper was left sacred. It was the crossword section. This favorite pastime was simply untouchable, even for the almighty censors. They were actually useful, as they occupied dull hours spent in bomb shelters, or kept people busy while waiting in endless lines for groceries.

Even though the news was tough for the British people during the first years of the war, after the crucial victory at El Alamein in 1942, which led to the Axis defeat in North Africa, the noose on the daily journals got loosened a bit, as more good news followed.

Soon after General Montgomery’s great success at El Alamein, an early probing mission of invading the French coast took place at Dieppe. The operation was turned out to be a bloodbath and a huge failure, but what caught the attention of MI5, the British counter-intelligence service, was that the town of Dieppe appeared in the Daily Telegraph‘s crossword section, just prior to the invasion.

There was no doubt about it―the clue was “French port”, and the answer was “Dieppe.” For a counter-intelligence officer, there is no such thing as a coincidence, so a thorough investigation followed.

The name of the man behind the suspicious word puzzle was Leonard Dawe. He was working a part-time job, compiling crosswords for the Daily Telegraph, while being a headmaster of Strand School―a London-based boy’s grammar school that was transferred to Effingham, Surrey County, during the war.

Despite all the operatives’ efforts, MI5 just couldn’t link the headmaster with any possible relations with the enemy. The 53-year-old teacher himself was utterly amazed when he was summoned for questioning. Something didn’t fit. Could it be that the enemy was delivering secret messages right in front of their noses?

Lord Tweedsmuir, who was in charge of the investigation, concluded his report: “We noticed that the crossword contained the word ‘Dieppe,’ and there was an immediate and exhaustive inquiry which also involved MI5. But in the end, it was concluded that it was just a remarkable coincidence–a complete fluke.”

Soon after came the historic agreement between Churchill and Roosevelt that the second front in Europe was absolutely necessary in order to defeat Hitler.

Preparations for D-Day were inbound, and a veil of secrecy once again covered the British Isles. Codenames were discussed with absolute discretion and everyone was instructed to be extremely cautious. The ones who weren’t were dealt with swiftly and without mercy.

One such case mentions a U.S. major-general, who apparently had a drink or two at a cocktail party and decided to speculate on the date of the invasion. He was immediately demoted and sent home to the United States.

The largest sea-borne operation ever to take place in the history of mankind incorporated 156,000 troops, so even though loose lips sunk ships, it was basically impossible to keep it a secret―at least not on the island of Britain.

10 Things you may not know about Sir Winston Churchill

In May 1944, Eisenhower decided that D-Day would fall on June 5, 1944. Around this time, various codenames were already agreed upon, such as “Overlord,” which was the name for the entire landing operation; “Neptune,” the codename for the naval support of the invasion; and the codenames for the beaches, where the landing would take place: Juno, Gold, Sword, Utah, and Omaha.

It was key to keep all the dates, the codenames, and locations at a top-secret level, for only that way the landing at Normandy could benefit from the element of surprise, thus maximizing efficiency and minimizing the casualties, which were already predicted to be heavy in any case.

But once again, the crosswords section of the Daily Telegraph started leaking information. First, it was the clue for “One of the USA,” the answer for which was “Utah.” Soon after, the word “Omaha” appeared.

After that: “Overlord” and “Neptune,” together with “Mulberry,” which was a codename for the floating harbor intended to provide logistics support to naval vessels in the upcoming invasion of France.

The author of the crossword? Leonard Dawe, once again.

Obviously, this was more than a “fluke,” as Lord Tweedsmuir had called it. The crossword puzzle potentially endangered the entire large-scale operation. Dawe was immediately apprehended for questioning.

But once again, the MI5 found nothing. It appeared that the man was either a super-spy, capable of fooling the entire staff of Her Majesty’s counter-intelligence or was in some way lucidly causing these coincidences, with the help of otherworldly forces.

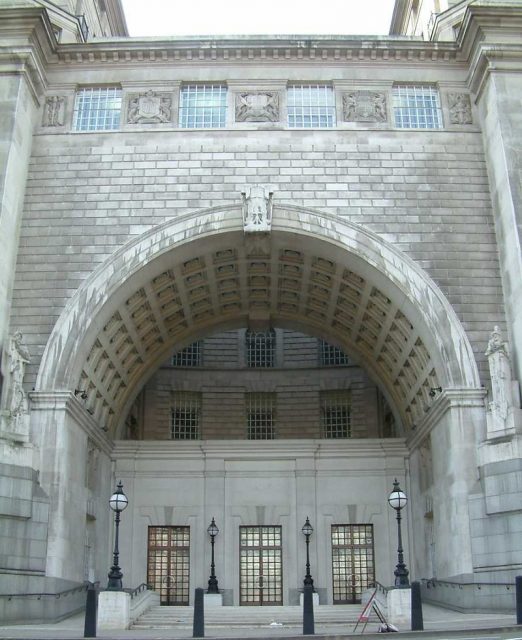

CC BY-SA 3.0

Operation Overlord went as planned, although the date was slightly changed from the 5th of June to the 6th, due to weather conditions.

Dawe was off the hook, but the coincidence and the alarm he caused with the secret service still puzzled the ones who were assigned to get to the bottom of it.

Later on, it was discovered that it wasn’t a coincidence after all, but it wasn’t an act of espionage either. Apparently, Dawe had a hard time thinking up the words that were to be put in the crosswords, so he would usually employ his students to provide him with interesting words, which often included common knowledge and geography.

Since the school was transferred to the countryside, it was located near one of the military bases which housed the U.S. and Canadian soldiers preparing for the assault. As D-Day was closing in, the codewords began circulating among low-ranking officers and even common soldiers.

The children, fascinated with everything revolving around the military, would often talk to the soldiers, or would innocently eavesdrop on their conversations, trying to learn as much as they could of their specific jargon. Thus, words like Utah, Omaha, Overlord, and many others were overheard by Dawe’s students, who would later report to him of the new words that they’d learned.

This was how the words-that-shouldn’t-be-spoken ended up in newspapers and were probably deciphered by hundreds of thousands of Daily Telegraph readers with a special flare for the crosswords section.

Fortunately for Allies, the Germans weren’t very keen on solving crosswords, for if they were, the largest amphibious assault in history could easily have been one of the largest military disasters of all time.

Nikola Budanovic is a freelance journalist who has worked for various media outlets such as Vice, War History Online, The Vintage News, and Taste of Cinema. He mostly deals with subjects such as military history and history in general, literature, and film.