People called them The Unholy Trio, audacious female gossip columnists when movies cost a nickel. The Hollywood “studio system” ruled and was manufacturing the dreams that got America through the Depression. The threesome brandished vast influence. For a star to diss any of them could result in the celebrity being quarantined to oblivion before he or she flamed out completely.

You probably know of Louella Parsons. For more than 30 years, she pledged unwavering loyalty to William Randolph Hearst’s Universal News Service, where she reigned as motion-picture editor. For a long time, Louella was the only game in town. Eventually, Louis B. Meyer and the other studio hotshots decided to encroach on Louella’s power by anointing an additional gossip columnist. Their choice was Hedda Hopper, 53 years old, who as a two-bit actress was a steady source of Louella’s insider items, which she’d bartered in exchange for her own publicity. Hedda began filing a column of her own, enabled by producers and studio moguls who steered exclusives her way.

Hedda’s career took off, though instead of one monster, now there were two. (I refer not exclusively to Hedda’s trademark millinery, dripping with birds and berries.) Louella and Hedda vied for whose pen had the most lethal poison. Yet in Hollywood history, Sheilah Graham, the third columnist completing The Unholy Trio, has been largely forgotten, and she—in many respects—is the most intriguing of all. Sheilah preferred a catch-more-flies-with-honey model, and was nobody’s puppet. Her approach worked, leading to a column that at its peak in 1966 was syndicated in 178 newspapers, more than the Mean Girls combined.

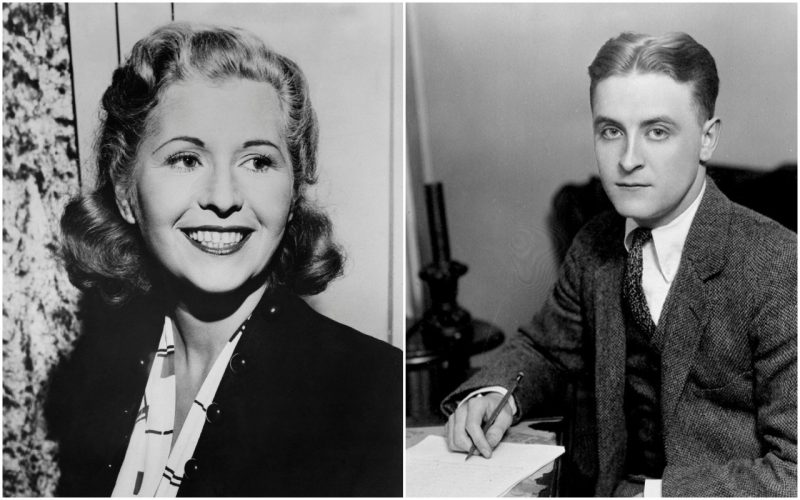

If Louella was the fat one and Hedda was the hat one, Sheilah Graham was that one, as gorgeous as a starlet. When a movie was made based on her 1958 bestselling memoir, Beloved Infidel, Sheilah thought Marilyn Monroe would have played her more fittingly than Deborah Kerr, who got the part. Both Marilyn and Graham were curvy blondes with uber-confidence in their sex appeal and self-esteem but crippled by shame about humble origins. In Sheilah’s case, her déclassé backstory, which she attempted to hide, make her triumphs all the more compelling.

She began life as Lily Shiel, the daughter of impoverished Jews who fled Ukrainian pogroms to settle in Stepney Green, a slum on London’s East End. Lily’s father died when she was young, forcing her mother to relinquish her daughter to the Jews Hospital and Orphanage, where she received her only formal education. This ended at 14 years of age, when Lily was ordered home to nurse her mother, who was dying of cancer. After her mama’s death, Lily began a process of reinvention that lasted a lifetime.

She began by cutting ties with Stepney Green. Lily moved to the more respectable West End, got a job selling toothbrushes, and married an adoring Henry Higgins-type. John Graham Gillam helped his bride shake off a Cockney accent, learn to hold a fork, and transform herself into “Sheilah Graham,” a dance hall performer of some acclaim. She was presented at court and in short order became a friend of Thomas Mitford and Randolph Churchill. (Those Mitfords, that Churchill.)

Soon, Sheilah traded the stage for writing Fleet Street fluff, and after a few years, left London for Manhattan. As a scrappy reporter with plummy speech and a glossy—if mostly fictional–history, Sheilah fit in fine. Along the way, she dear-Johned dear John, although she supported him for the rest of her life, because Sheilah was as generous as she was industrious. The setting soon shifted to Hollywood, where–with more chutzpah than contacts—she became a gossip columnist.

Glamorous Hollywood leading Ladies Quotes

Enter F. Scott Fitzgerald, literature’s 1920’s, golden boy. In 1937 he was 40, more or less obsolete, seen as a reactionary who worshiped the rich although he himself was now deeply in debt, having spent his vast royalties on too much pink champagne along with sanitariums for his mentally unbalanced wife, Zelda. Like Dorothy Parker and others in his East Coast crowd, Scott hit up Hollywood, where polished writers were earning handsome wages for screenplays.

On one of Scott’s first evenings in Tinseltown, he attended a party thrown for Sheilah, newly betrothed to a marquess, no less. For Scott, she might have been the ghost of 1920s Zelda. For Sheilah, he was a curiosity: a famous author. Undeterred by the diamond as big as the Ritz on her finger, he invited Sheila to a Sunset Strip nightclub. Mid-tango a few nights later, a legendary romance began.

Theirs was a relationship built on instant chemistry, wicked humor, and mutual respect for one another’s intelligence. Scott was a born teacher and Sheilah, a student eager to pick up where she left off. For two years, the couple worked their way through a syllabus Fitzgerald created spanning the humanities. They acted out Russian novels, recited T. S. Eliot while swing dancing, and chewed through contemporary politics as they listened to Beethoven. To friends, Scott bragged about Sheilah’s nimble brain. Their crash course whet her intellectual appetite, and she continued educating herself, basically, forever.

Along the way, what became of Sheilah’s Judaism? In England, she kept it a secret—anti-Semitism was rampant—and when she crossed the pond, she allowed her roots to remain deep background. Ultimately, however, the urge to disclose the truth to Fitzgerald overwhelmed her. When Sheilah came clean, the man who worshiped Hollywood’s legendary Irving Thalberg pointed out how many movie magnates were Jewish. Sheilah countered by reminding the author that his own novels perpetuated stereotypes. Exhibit A: Meyer Wolfschein of The Great Gatsby. Fitzgerald argued that he wasn’t, at heart, malicious, and proved himself able to change in a novel he started in 1940. The Last Tycoon was written with Sheilah as his inspiration for the character Kathleen. Monroe Stahr, the book’s hero, is clearly Jewish.

Sadly, Fitzgerald did not live to complete the novel: He died in Sheilah’s living room at only 44. Heartbroken, she moved to London to exercise her serious reporting chops as a correspondent covering World War II, interviewing George Bernard Shaw and other heavyweights. After the war, she returned to the States, married three more times—briefly—and had two children who were rumored not to be fathered by the men on their birth certificates.

Sheilah continued her movie reporting, eventually broadening it to include public figures, and demanded a salary equal to the stars she celebrated. Eventually, she segued into radio and, later, television. In 1951 she starred in a TV interview show that set the stage for “The Tonight Show” and the avalanche of pop culture media coverage that we’ve known ever since. Along the way, she wrote 11 more memoirs: the constant throughout them was her relationship with Fitzgerald.

“I’ll only be remembered, if I’m remembered at all, because of Scott,” Sheilah told the San Francisco Chronicle. This was one way in which she sold herself short. Fitzgerald was an intriguing romantic footnote to her life, but Sheilah Graham was so much more than a great author’s girlfriend and champion. She was a feminist decades before the word was invented, never relying on a man as a meal ticket while raising her children, and blazing a lucrative four-decade career. Through her TV exposure she opened the door for Barbara Walters, Oprah, and legions of luminaries who’ve followed. Along with Louella and Hedda, Sheilah paved the way not just for entire television networks, but the TMZ-ing of our culture.

Quite a legacy, little Lily.

Sally Koslow is the author of the novel Another Side of Paradise, about Sheilah Graham and her tumultuous relationship with F. Scott Fitzgerald.