Ferns in the Victorian age were much more than just a plant. In the mid 19th century, a rare but highly contagious “disease” swept through British society. It caused swooning and fainting and even resulted in a few deaths. For nearly 50 years, many fashionable people fell victim to Pteridomania, or “fern fever.” That’s right, a passion for plants.

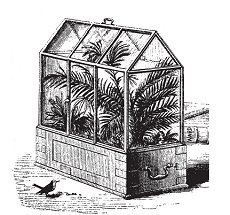

The seed of the craze started in 1828 when botanist Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward couldn’t grow ferns in London’s polluted air. But when he noticed fern seedlings thriving in the bottom of glass jars, he built a specific case for growing them. “Wardian cases,” as they came to be known, were essentially proto-terrariums: ornamental miniature glass houses with dirt on the bottom for plants. Victorians became enamored of the idea of growing and collecting plants inside the enchanting cases. The passion for ferns spread like a contagion.

Ward’s friend George Loddiges grew ferns in his grand nursery and promoted them in an illustrated catalog to discerning would-be horticulturalists; at the height of the craze, Loddiges offered as many as 80 exotic fern varieties.

In the repressed Victorian era, ferns were a covert way to express sexual desire. Moist, fringed, and shady, ferns were associated with females’ nether regions and even had names that explicitly addressed that fact. The maidenhair fern, for example, was a euphemism for pubic hair, according to James A. Duke’s Handbook of Medicinal Plants of Latin America: “The name in English is doubtless a salacious extension.”

Fern-hunting parties became popular, allowing young women to get outside in a seemingly innocuous pursuit with less rigid oversight and chaperoning than they saw in parlors and drawing rooms. They may have even had the occasional romantic meetup with a similarly fern-impassioned beau.

“Your daughters, perhaps, have been seized with the prevailing ‘Pteridomania’ and are collecting and buying ferns,” Charles Kingsley wrote in 1855 in his book Glaucus, or Wonders of the Shore. Kingsley was a priest, professor, and social reformer, who counted among his friends Charles Darwin. “And wrangling over unpronounceable names of species, (which seem to be different with every new fern that they buy), till the Pteridomania seems to you something of a bore.” Kingsley wasn’t all scold. He did admit that “you cannot deny that they find enjoyment in it, and are more active, more cheerful, more self-forgetful over it, than they would have been over novels and gossip, crochet or Berlin wool.”

Pteridomania—the term Kingsley coined—came from the Latin pterido for fern.

Related Video:

https://youtu.be/utw0IVJcGK0

The passion for ferns emerged as a trendy decorative motif in textiles, pottery, paper, teapots, chamber pots, and gravestones. Amateur botanists took up the fashionable hobby, and traveled among the British Isles collecting specimens. The affair with all things fern lasted for nearly 50 years, until the 1890s.

Pteridomania was seen primarily as a British eccentricity, but there is evidence that the fever crossed the pond to greenhouses in Philadelphia, Chicago, and Detroit. The particularly passionate and prosperous would show off their collections in carefully constructed outdoor ferneries. If that were out of reach, a book of collected, pressed, and dried ferns might do—the flat leaves held up well.

While it seems like a harmless pursuit, the zeal of the Pteridomaniacs resulted in some species in the Devon countryside becoming nearly extinct. The Irish Killarney fern is endangered to this day. A few would-be botanists plunged to their deaths over cliffs while trying to reach particular specimens. In 1865, the fern shortage had become so severe that writer Nona Bellairs called for laws to protect the plants: “We must have fern laws, and protect them like game!”

Related story from us: Most Victorian-era boys wore dresses and the reasons were practical

There turned out to be no need for restrictive laws, however. The Victorian ferns phase passed with the turn of the century, and by the early 1900s, fashionable ladies turned to other passionate pursuits. Nature had run its course, as it were.

E.L. Hamilton has written about pop culture for a variety of magazines and newspapers, including Rolling Stone, Seventeen, Cosmopolitan, the New York Post and the New York Daily News. She lives in central New Jersey, just west of New York City