Not everything that happens in Vegas stays in Vegas.

The city used to blow up its old hotels and casinos like other towns host fireworks displays. The impeccably tailored Rat Pack has been replaced by the sloppily inebriated Wolf Pack from the Hangover movies.

That’s why the enduring legacy of designer Betty Willis is so impressive. Her neon-lit signage has survived changing tastes; moreover, her most famous creations have outlasted the resorts that they were created for.

Her most iconic work, the “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign, has become emblematic of Sin City itself. The story of the lights of the glittering Las Vegas strip begins with the discovery of neon in 1898 by the British scientists William Ramsay and Morris W. Travers.

It didn’t take long for inventors to figure out how to trap the gas in glass tubes twisted to form jazzy shapes and typography: By 1913 a large sign for the vermouth Cinzano lit the night sky in Paris, and neon lighting quickly became a popular fixture in outdoor advertising.

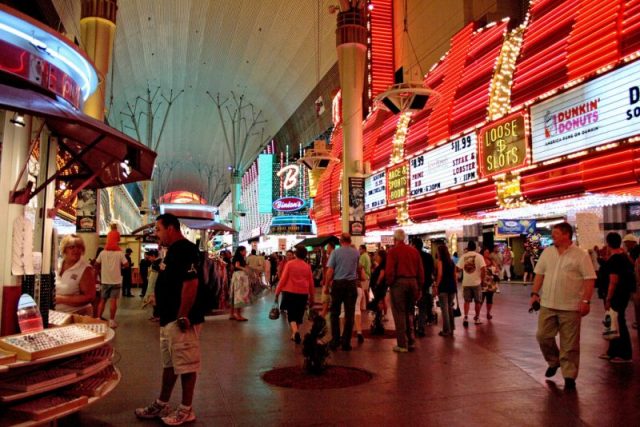

Neon itself was a draw because it was a novelty. And because neon signs were also visible in daylight, they became a popular way to advertise motels and restaurants to travelers passing through the otherwise barren stretches of desert.

Las Vegas as a destination was also shiny and new. Before gambling was legalized in 1931, it was a dusty railroad town.

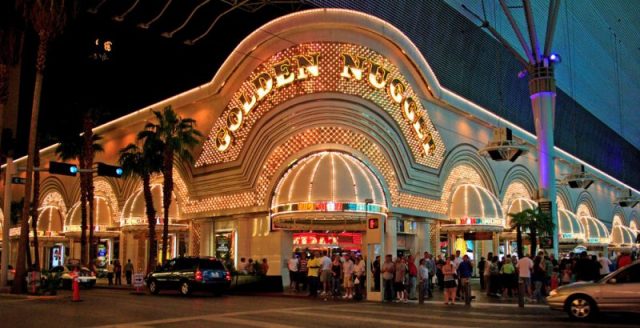

During WWII, with the addition of an Army airfield and other military activities, the place’s population doubled, which drew the attention of notorious figures like Meyer Lansky and Bugsy Siegel. And they built opulent casinos to attract high rollers and big money.

As luxurious as these showrooms, resorts, and gambling dens became, they still needed neon to help them stand out from the competition. This is where Willis comes in. Born in 1923 in Everton, Nevada—a town just outside of Las Vegas—she had parents who were among the original settlers of Las Vegas, and they instilled their trailblazing spirit in their daughter, the youngest of eight children.

Willis had shown a talent for illustration and design, and she left Las Vegas to attend art school in 1942. Aside from showgirls and slot machines, Nevada was also a magnet for people seeking quick marriages and fast divorces.

When she returned to her hometown, she first got a job at the county courthouse, where she made sure that revealingly dressed divorcées-to-be were modestly dressed before they appeared in front of a judge.

Basically, Betty was as Las Vegas as one human could be. By all accounts, she was a fun but feisty lady, twice divorced herself and a lover of salty language. But it was still difficult for a woman to get a job in the field she had trained in. She would not be put off, either. After another brief but respectable stint as a legal secretary, she found employment at a sign-making company called Western Neon.

Willis once said, “When you work with neon signs, you have to not only design them, but you have to learn the nuts and bolts of how neon, light and electricity work. You have to learn about pressure points and weight and wattage of lamps. You work with engineers as well as artists.”

Back then, most designers—male or female—weren’t interested in such technical stuff.

Willis’ earliest endeavors were for more modest businesses such as the Bow and Arrow and Blue Angel Motels. But even then, her designs were eye-grabbers and emblematic of a fresh, modernist take on typography and architecture known as Googie Style, which originated in Southern California during the late 1940s and was influenced by car culture, jets, the Space Age, and the Atomic Age.

Las Vegas in the 1950s and 1960s was also an oasis in the cultural desert. For female designers like Willis and African-American architects like Paul Revere Williams, the building boom provided more opportunities to create forward-thinking projects than in other cities. Partially because their clients were often outsiders themselves.

Take, for instance, the Moulin Rouge, which opened in 1955. Built at a cost of $3.5 million, it was the first fully integrated hotel casino in the United States. Until that time, almost all of the casinos were off limits to blacks unless they were there as entertainment or part of the labor force.

The Moulin Rouge was as extravagant as any complex on the strip. It consisted of a hotel, casino, and theater, all housed in two Googie-style stuccoed buildings. “Moulin Rouge” was written across the façade in pink-neon cursive writing. This sign was designed by Betty Willis.

As time progressed, so too, did technology. More neon colors became available for sign makers. And designers kept discovering new ways to animate their creations. “Everything you could flash or spin, we did it,” Willis said in an interview with the New York Times in 2005.

CC BY-SA 3.0

Willis’ most famous creation is, of course, the “Welcome to Fabulous Las Vegas” sign. The concept for the marquee came about when a group of casino owners and civic leaders decided to erect a roadside “Welcome” sign.

These gateways were popular in the post-war era and her boss at Western Neon, Ted Rogich, approached her to come up with a concept that they could pitch. The duo sold their design to Clark County for $4,000.

Each letter of the word “Welcome” is outlined in neon and centered in white circles representing silver dollars. Around the perimeter of the diamond-shaped sign are yellow bulbs that flash and move in a chasing sequence.

Willis also came up with the idea of adding the adjective “fabulous” to the sign to differentiate it from other “Welcome To” signs. Because Las Vegas was, well, fabulous.

Today, the sign is one of the most popular attractions in Las Vegas, with people lining up to get a selfie with it in the background. It’s hard to imagine Las Vegas without Willis’ neon legacy, but in 2008 preservationists fought to have the sign added to the National Register of Historic Places.

And while the Motels and Casinos that once proudly displayed her signs are long gone, Willis’ unique take on electric typography lives on at the Neon Museum in Las Vegas.

Willis herself continued working well into her 70s. She died in her home in Overton on April 19, 2015. On May 5, 2015, Clark County declared May 5th “Betty Willis Day” to honor her legacy.

RhondaRiche is an award-winning Toronto-based lifestyle writer with a particular obsession with watches. Riche is also fond of art and design and is the co-author of the book ‘Covet Garden Home.’