For those familiar with the six wives of Henry VIII, his fourth queen, Anne of Cleves, has become either a punchline or a heroine. The first label is unfair, and the second one wishful thinking.

After the death of Queen Jane shortly after she gave birth in October 1537, Henry VIII managed to rouse himself from depression and set his ministers, courtiers, and even a royal painter, Hans Holbein, to the task of finding him a new wife.

After a long search, the 47-year-old king decided on a German princess, 24-year-old Anne of Cleves, in 1539.

They married on January 6, 1540–and yet on July 6th of that year, Queen Anne was informed that her husband wanted an annulment.

The marriage was never consummated, and throughout it the king complained to others that he found her extremely unattractive.

“I like her not,” he said after meeting her for the first time, shortly before their scheduled wedding date.

Anne of Cleves did not oppose the annulment and accepted the property and income Henry VIII settled on her, living quietly as his “sister.” She outlived the king, dying on July 16, 1557, at the age of 41, the last of the six wives to go.

Those are the facts of her life and brief reign as a Queen of England. But what about the woman herself–what did she think of her marriage, why did she provoke such strong dislike from Henry VIII, and how did she feel about her humiliating rejection?

To begin, it’s important to establish the reality that in the 16th century royal marriages were about forging diplomatic alliances between countries. With a princess bride often came a promise of an army if need be and a large dowry to fill the treasury.

Henry’s contemporaries, the rulers of Spain, France, and Scotland, all married for reasons of state. If love sprang up between the couple, that was fortunate, but if it didn’t, the royals made the best of it.

At first, the Tudor monarch was just like the other European rulers. Henry VIII’s first wife, Catherine of Aragon, was a Spanish princess, and it seems likely that he was eager to marry her (his older brother’s widow) because he wanted to join forces with her father, King Ferdinand, and declare war on France.

After a long marriage, during which he did briefly wage war on France but he did not gain a son, only a daughter, Henry VIII pushed for an annulment.

It was considered unusual, if not shocking, that Henry VIII’s second and third wives were English women whom he chose for love.

The second wife, Anne Boleyn, who was probably the love of his life, was executed for adultery and treason in 1536. She was rapidly replaced by the demure Jane Seymour, who gave the king a son before dying.

Henry VIII showed no interest in selecting another attractive young woman of his court.

He was prepared to marry a royal once more for the good of the country, and his first choice was a beautiful young princess who was actually a relative of his first wife, Christina of Milan.

But she is supposed to have said, “If I had two heads, one would be at the King of England’s disposal.”

France and Spain declared themselves allies in 1539, which was very threatening to Henry VIII, especially since the Pope had encouraged those two Catholic countries to wage war on England, which had broken away from the Catholic Church. He feared encirclement and invasion.

The king’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, suggested a counter-alliance with a Protestant German kingdom, Cleves, through marrying one of the sisters of Duke William of Cleves. This duke was an aggressive young man, eager to get into European conflicts.

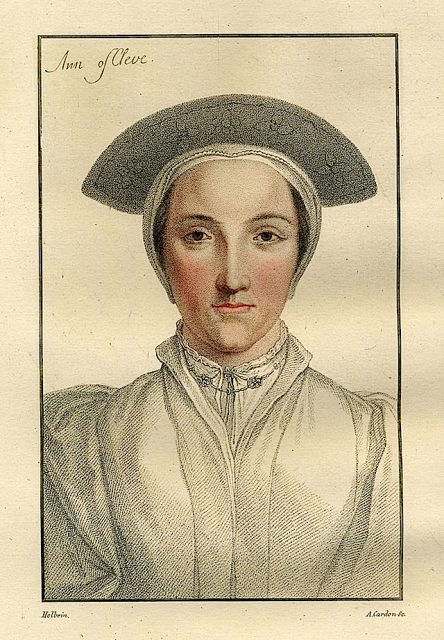

Court artist Hans Holbein was sent to Cleves, and his painting of Anne, the oldest of the sisters, intrigued the king.

She looked appealing to him, and certainly, when her portrait is compared to that of his third wife, Jane Seymour, she is at least as good looking as her, to our modern eye.

Most importantly, Anne of Cleves would deliver an alliance to help England, she could perform the duties of queen, and she would hopefully have children, to strengthen the Tudors’ rather tentative hold on the succession.

The way that Anne’s background differed from that of the English royals was that the German princess weren’t taught to play any musical instruments or know much about poetry or art.

Anne’s mother was extremely religious and her priority for her daughters was faith–and needlework.

If Henry VIII knew about this culture gap, it didn’t seem important enough to stop a royal wedding.

The marriage contract was signed, and Anne traveled to Calais, in France, to make the crossing.

What struck many who met her was that she seemed like a serious young woman, determined to be gracious to everyone she met and to be a good queen.

She had a lighter side too, enjoying her lessons in playing cards in Calais after hearing that it was a favorite pursuit of her future husband’s.

By the end of 1539, Anne of Cleves was in England along with her German entourage but had not yet reached London. It was the coldest time of the year and they couldn’t move too quickly.

This was the moment when the middle-aged king seemed to have forgotten his priorities and decided to act like a young man of a chivalrous, romantic age.

Henry VIII was so impatient to meet Anne, he decided to play a game. He and his courtiers would ride to Canterbury, where she was staying before continuing on to London, but in disguise. He would “woo” his bride himself.

By all reports, Anne of Cleves was standing at an upstairs window, watching a bear baiting with interest, when a group of gentlemen suddenly entered the room and walked up to her. There was one man in particular, very tall and quite overweight, who thrust himself forward. Eyewitnesses said she turned away from all of them, displeased by the intrusion and uninterested in her strange guests, and returned to watching the bear.

The men retreated, but a short time later returned, and this time the tall, fat man wore luxurious robes and furs. He announced he was the King of England.

We do not know which language they conversed in, because Anne of Cleves couldn’t speak English. It was most likely French. But no matter which language used, it was a disaster. Anne of Cleves had been anything but taken with her future husband when he was incognito, and there was just no denying it. The two of them conversed awkwardly, and the King left.

Their relationship never recovered. Henry VIII declared she was “nothing as fair as has been reported.” He said he was angry about his new wife’s appearance and her manner; he particularly hated her clothes. It is said that he shouted angrily about being sent a “Flanders mare,” but there is no evidence in the contemporary documents that Henry used those words.

It is worth taking a moment to compare this reaction to a similar royal marriage 200 years later. King George III agreed to an arranged union with a young German princess who was not at all sophisticated.

When Princess Charlotte arrived in England and her future husband met her, witnesses say he was taken aback by her plain looks. But he made an effort to get to know her, they married, and had 15 children.

Back in London in 1540, Henry VIII told his ministers to get him out of the marriage. If he had sent Anne of Cleves back to her brother and mother, that would have been an act of appalling cruelty, but he didn’t care. The men who served the king, after studying the marriage contract and treaties, said they found no loopholes.

Ye Olde English insults we could use today

Henry VIII married Anne of Cleves in Greenwich with splendor, pretending to the public that all was well. What is interesting is observers thought the Queen was very attractive: “her hair hanging down which was fair, yellow and long.” But the next day, he told Cromwell they didn’t consummate the marriage. “I liked her before not well, but now I like her much worse.”

Some historians believe that Henry VIII’s not being attracted to Anne of Cleves on first meeting her became a crisis because he knew that he would find it very difficult to do what kings must do with their wives. Henry had a problem with impotence.

During the trial of his second wife, Anne Boleyn, it was revealed that she said the King had “neither skill or vigor” in bed. After marrying Jane Seymour, Henry had confided in one man that he didn’t think he would have any children with her.

Jane did give birth to the future Edward VI. But during his next three marriages, there were no pregnancies as he became more obese and sickly–and irrational and tyrannical.

How did Anne of Cleves feel about this mess? Some believe that she was so ignorant of the facts of life that the thought her husband kissing her on the cheek was enough for a successful marriage.

However, in no time Henry VIII was besotted with a teenage girl who was a maid of honor to his wife named Catherine Howard, who was by all accounts pretty and graceful (and sexually experienced, but she kept that a secret).

It is known that Queen Anne complained to her Cleves ambassador to the English court about her husband being involved with Catherine Howard. Henry might have been cold to her, irritable, with ulcerated legs that stank, but she minded.

At the same time, Anne put all of her efforts into being a good queen, and in a short time became popular with the public.

Nonetheless, the king told her he wanted an annulment–not personally, of course. He had several courtiers approach her and tell her the news. ( Cromwell was not among them, for he was executed that summer, in part for not getting the king out of his fourth marriage quickly enough.)

After showing some distress, Anne of Cleves agreed to the annulment.

Some people assumed she would return to her homeland, but she didn’t. It is thought that she didn’t want to face her brother and deal with his anger over the situation. And Henry VIII offered her a very good settlement.

Many people think that Anne of Cleves got the best deal of all six wives in divorcing Henry VIII and securing his money without having to live with him or face the dire fates of other queens. To them, she was a winner.

However, the truth is that Anne wanted to be Queen of England, she was brought up to play an important role in Europe, and after Henry’s next marriage ended in Catherine Howard’s execution for adultery, she wanted to be taken back as his wife, and return to court. She asked her ambassador to make inquiries.

The King wasn’t interested, and Anne lived the rest of her life in her various homes, surrounded by servants and occasionally seeing her stepdaughters Mary and Elizabeth. She had little to do; there was no role for her in court. She never remarried. Once her stepson Edward became king, her income was reduced.

Anne of Cleves died after her stepdaughter Mary became queen, a survivor but still a victim of Henry VIII.

Nancy Bilyeau has written a trilogy of novels set in the court of Henry VIII: ‘The Crown,’ ‘The Chalice,’ and ‘The Tapestry.’ The books are for sale in the U.S., the U.K., and seven other countries. For more information, go to www.nancybilyeau.com