Somewhere in the far north of the Asian continent, close to the Arctic Circle, time seems to be going backward.

That is if you look at it in geological terms. The area on the Kolyma River, in northeastern Syberia, nicknamed Pleistocene Park, is functioning as a nature reserve in which scientists are trying to turn today’s tundra into a steppe-like grassland, which was there during the Ice Age, some 11,700 years ago.

Contrary to the tundra region and vast forests that surround it, the Pleistocene Park today is a modest 6.2-square-mile (1,600 hectares) reservation inhabited by moose, elk, reindeer, muskoxen, bison, and Yakutan horses that roam freely across grass-covered plains.

It all started in 1988, when a Soviet scientist name Sergey Zimov put in practice his hypothesis regarding the extinction of several herbivore species in the Siberian tundra after the Ice Age.

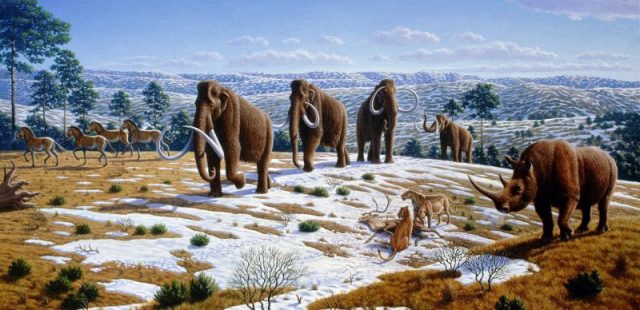

Despite its name, the Ice Age was pretty mild in these parts of the world, as the region was covered in green grass, providing food for a variety of wildlife.

The final years of the Pleistocene epoch commenced 2.6 million years ago, causing the extinction of mammoths, woolly rhinoceros, and other large mammals commonly referred as the Megafauna.

Even though their extinction is usually considered the consequence of extreme climate change, Zimov begs to differ, claiming that the human factor was key and that overhunting led to the disappearance of these particular species.

But the Pleistocene Park is not a time-traveling adventure just for the fun of it, as its true purpose is to look into the past in order to secure a safe future for all of us.

The nature reserve is, in fact, a testing ground for a revolutionary new method of battling global warming.

The key concept behind this project is that animals, rather than climate, maintained the ecosystem.

The presence of large herbivores that trample snow in order to get to the grass beneath it helped cool the ground, thus preserving the permafrost layer of soil.

Now, to fully understand the project and its relation to the future of the Earth and prevention of further global warming, we need to make a quick introduction of permafrost and the way it affects global climate changes.

Permafrost ― a layer of ground kept in permanent below-zero temperature ― can mostly be found in and around the Arctic and Antarctic regions, although it exists in alpine areas, at high altitudes.

Alexander Khimushin Spends Six Months Photographing Siberia’s Indigenous People

Permafrost contains more than a trillion tons of carbon, which originates from remains of organic matter deposited over the course of millions of years.

It is in Earth’s best interest that this carbon remains frozen, for if the permafrost fails to contain its regular temperature and starts to thaw, it would initiate a huge emission of carbon dioxide and methane, which are both greenhouse gasses, accelerating the global warming process.

This is most likely to happen if Arctic temperatures rise between 1.5 and 2.5 degrees Celsius by 2040.

Siberia is considered one of the most likely places on Earth where such a scenario might occur, and if it does, we might face a worldwide catastrophe. In order to stop that from happening, Sergey Zimov needs to create conditions for the re-appearance of the so-called Mammoth Steppes.

This is achieved by utilizing herbivore animals that destroy some types of vegetation like trees and moss, disrupt the snow by trampling it in search of food, and fertilize the ground, thus encouraging more grass to grow in the summer, while providing stronger cooling of the ground in the long winter months.

But the larger area is currently still covered in forests, moss, weeds and willow shrub. What Zimov argues is that in order to keep the permafrost from releasing its carbon, it is necessary to re-create ancient ecological niches.

This would include partial de-forestation, as trees tend to increase ground temperature.

So does the snow, for it serves as a sort of a sheet covering the ground. Instead of investing billions in creating the Pleistocene conditions by using machines and technology, Zimov suggests letting nature run its course ― with just the initial guidance of man’s hand.

That is why Sergey Zimov, together with his son Nikita, have dedicated their lives to reversing the trend of global warming, and as for their experiment ― it sure does provide hope.

Horses, moose, bison, muskoxen, and others that were brought to the Pleistocene Park have successfully reduced the ground temperature by 2 degrees already.

The ratio of energy emission and energy absorption has been monitored for more than a decade now, using advanced technology, and the results are showing promise.

But this relative success needs to be duplicated in other high-latitude areas where the threat is more significant. Let’s just hope their effort gets wider recognition.

The plan is to apply these methods all across the Arctic permafrost, from the northernmost parts of Russia, well into the North American continent.

After a successful crowd-funding campaign in early 2017, 12 domestic yak and 30 domestic sheep were brought to the Pleistocene Park, as popular support for the project grows every day.

Perhaps we will live to see the entire Arctic landscape transform into mammoth steppes, as global warming becomes an increasingly relevant topic of discussion among scientists and world leaders alike.

Nikola Budanovic is a freelance journalist who has worked for various media outlets such as Vice, War History Online,The Vintage News, Taste of Cinema,etc. He mostly deals with subjects such as military history and history in general, literature and film.