Traveling down the B3098 near Westbury, in Wiltshire, England, a curious sight greets drivers and passengers alike as they round a corner.

Up on a hillside, in clear view, is a large, white horse. Not an actual horse and not a statue, but a carving, in the earth, of a horse.

This is the Westbury White Horse, and it is interestingly not a unique figure in the United Kingdom.

The horse, in profile, has been carved into the white chalky escarpment of Salisbury Plain, about 1.5 miles east of the town of Westbury. It is one of the oldest of several white horses in Wiltshire and lies near an Iron Age hill fort.

At 180 feet tall by 170 feet wide, it is uncertain who carved the figure or what it represents, however it is often thought to commemorate the victory of King Alfred at the Battle of Ethandun, which took place nearby in 878 A.D.; that being said, there is no evidence of this claim until the 18th century.

The white horse has been considered a symbol of the Saxons of the early Middle Ages, including the fabled figures of Hengest and Horsa, who are said to have led the first Anglo-Saxon invasion of England.

Whatever its origins, the Westbury White Horse has gained other-worldly status through the ages, and is said to go down to the Bridewell springs to drink each night when the nearby Bratton church clock strikes midnight.

Also in Wiltshire, about 20 miles northeast of the Westbury White Horse is the Cherhill White Horse, sometimes called the Oldbury White Horse.

Like its neighbor, this figure is also in profile, and its feet are placed in such as way that it looks like it is taking a stroll across the hillside.

It can be found slightly below Oldbury Castle–an earthwork, as opposed to a bricks and mortar castle. Its origins are rather recent, being carved into the hillside in 1780 by Dr. Christopher Alsop.

The Marlborough White Horse is another “recent” addition to the Wiltshire landscape.

It was carved in 1804 by students at Mr. Greasley’s Academy and is the smallest of the Wiltshire white horses. In all, there have been as many as 13 white horses in Wiltshire alone; only eight can still be seen, as the others have grown over.

The Uffington White Horse is another chalk figure, but it dates from a much earlier period.

It is believed to have been carved into the hillside near the town of Uffington, in Oxfordshire, sometime during the late Bronze Age, between 1380 B.C. and 550 B.C.

It was not just scratched into the chalk hillside, but rather dug in, up to 3 feet deep.

Whoever carved it, meant it to stay. Whereas the Westbury horse is a solid profile–it’s clear to see that it’s a horse–the Uffington figure is more abstract, with a thin body, a mere outline of the top of the neck, and spindly legs.

The head is more of a suggestion, with ears, one eye, and a sort of mouth. And, while the Westbury horse is standing still, surveying its surroundings, the Uffington horse is in full gallop, speeding across the hillside.

The horse is “scoured” every seven years, to remove the vegetation that quickly encroaches on it over a short period of time.

During the Second World War, however, it was covered up with grass and hedges so that Luftwaffe pilots could not use it as a navigational tool during their bombing raids over the UK.

There are two well-known human-like figures found on the hills of the UK as well. The Cerne Abbas Giant is in Dorset and is 180 feet tall.

The outlined figure is an unclothed man holding a rather nasty-looking club. Its age and purpose are unknown, although the earliest reference is from the late 1600s.

Photo by Cupcakekid CC BY 2.5

Similarly, the Long Man of Wilmington, located in East Sussex, is also a line drawing of a human figure, holding 2 staves–one in each hand.

Like the Cerne Abbas Giant, the Long Man’s origins are unknown, and the earliest known reference was a drawing made by William Burrell in 1766.

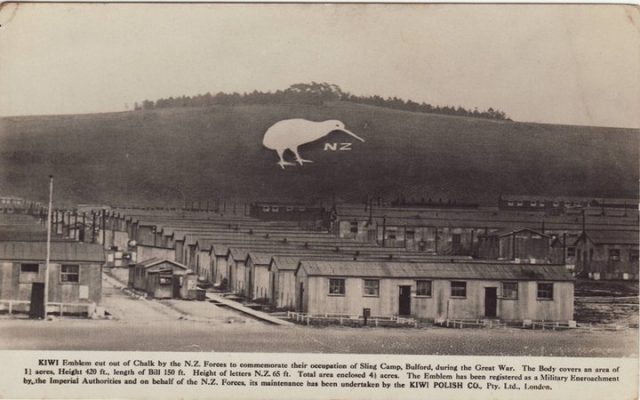

Finally, and perhaps the oddest of the chalk figures in the UK, the Bulford Kiwi can be found on Salisbury Plain in Wiltshire, less than 30 miles from the Westbury White horse.

This figure, as one could probably guess, is not ancient. Rather, it was carved into the soft chalk hillside in 1919 by soldiers of the New Zealand Expeditionary Force at the end of the First World War, while they were stationed in England before returning home.

Whether ancient or recent, the chalk emblems that adorn hillsides in the southern United Kingdom are worthy of a visit.

Their origins may be blurred by time, but through restoration and ongoing dedicated maintenance, they will all be around for future generations to enjoy.

Patricia Grimshaw is a self-professed museum nerd, with an equal interest in both medieval and military history. She received a BA (Hons) from Queen’s University in Medieval History, and an MA in War Studies from the Royal Military College of Canada, and completed a Master of Museum Studies at the University of Toronto before beginning her museum career. She has lived and traveled all over Canada and Europe.