What do you do when you encounter a gorilla? For decades, the answer might have been to scream and run.

Gorillas were wild beasts that could tear cities apart, or so many thought based on the movie King Kong. Textbook instructions of what to do stated that one should sit quietly and observe the creatures.

But that’s not what Dian Fossey did.

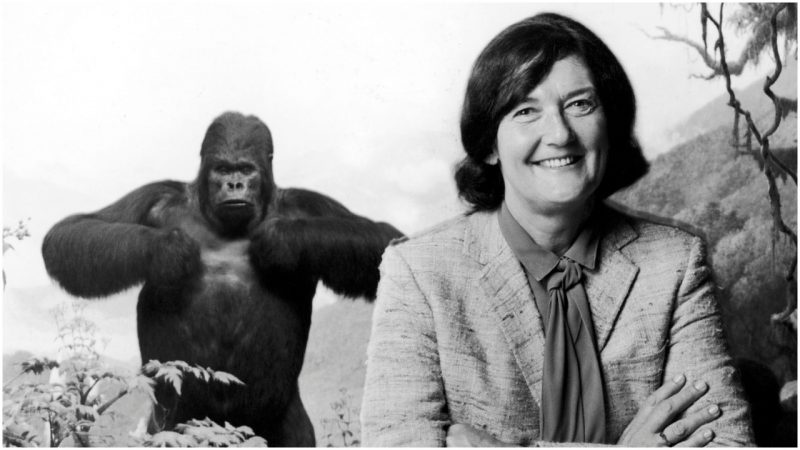

Considered by many to be the Jane Goodall among gorillas, Fossey took to imitating the animals.

Mirroring is a communication tool that humans can use to signal unity and togetherness and surprisingly the apes picked up on that.

Walking around on her knuckles, chewing on celery stalks, imitating their feeding and grooming habits as well as their sounds, and maintaining a non-threatening profile, she was able to infiltrate the gorilla society.

“The gorillas have responded favorably, although admittedly these methods are not always dignified,” she wrote. “One feels a fool thumping one’s chest rhythmically, or sitting about pretending to munch on a stalk of wild celery as though it were the most delectable morsel in the world.”

Her journey with the primates wasn’t an easy one. On her first expedition, shortly after she set up camp, she was captured, raped, and held prisoner by Congo rebels.

She managed to escape by bribing them with a Land-Rover and cash if they would drive her to Uganda, where she would give them their reward.

When they arrived in Uganda, her capturers were arrested and imprisoned, and she was set free. After the traumatizing event she didn’t go home, however. She regrouped and went straight back to the mountain–this time on the Rwanda side.

There she set up camp and made friends with the Rwandese mountain gorillas.

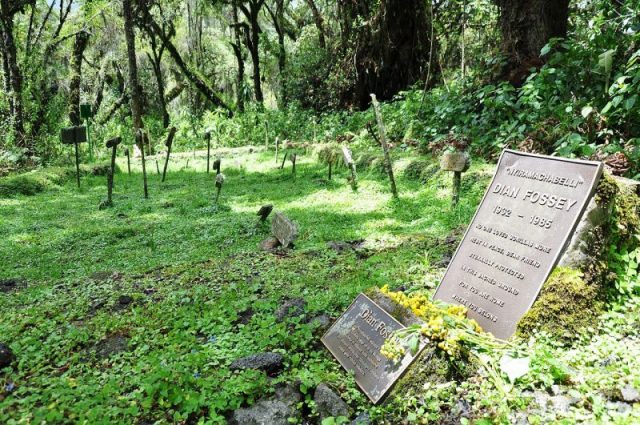

The Rwandan locals called her Nyiramachabeli–the woman who lives alone on the mountain. For Fossey, the easiest and most satisfying relationships she had were the ones with the gorillas.

They became the family she never had. She could identify each one by the specific characteristics of their noses. Similar to fingerprints, gorillas have unique wrinkle patterns around their nose which she used to identify them.

Once she was able to tell them apart, she began to name them: Digit, Rafiki, Uncle Bert, etc.

Although Fossey is a lone wolf in her research and life among the gorillas, they are not alone on the mountains.

Poachers invaded the area and herders in the region set traps for their main prey, the antelope, but often sadly snagged an unsuspecting gorilla.

Silverback Gorilla Shows Off Strength In Front Of Zoo Visitors

These groups became Fossey’s enemies. In fact, when she was first trying to gain the trust of the Rwandese gorillas, they were very reluctant to accept her since they were used to the poacher’s version of a monster mankind, who was consistently hunting them down.

Tragedy struck in 1977 when Fossey happened upon the remainder of Digit’s body in the jungle.

His head and feet had been cut off. Out of all of the gorillas she had formed a special bond with Digit, and this tragedy was a huge blow to her.

Her fight with the poachers became a personal one and from then on out, it was a war against all of mankind who caused harm by trespassing onto the gorilla territory.

Fossey became a bitter woman that year. Her relationship with the authorities had worsened as well as her relationship with the other researchers who had steadily been coming up the mountain to work alongside her.

Even with the locals her relationship worsened: She thought them to be lazy, corrupt, and incompetent.

She had no shortage of ill-wishers and to make matters worse, in 1978 the American Wildlife Fund started to bring tourists up the mountain to see the gorillas.

There were a number of reasons why the AWF initiated this program. They wanted to train the Rwandan people on the importance of the gorillas not only to wildlife but also to the Rwandan economy.

Gorilla tourism was not a concept that Fossey was on board with. She hated the tourists coming in and disturbing the peace of her beloved primates.

It’s said that she once fired several shots in the air when Dutch tourists came up the mountain uninvited.

She became increasingly intense and aggressive, and her work became more and more counterproductive. For this reason, the American embassy found her a temporary position at Cornell University.

There she finished writing her book and took a break from the stress of jungle life. She could never fill the hole in her heart where her gorilla family belonged, so after just three years she returned in 1983.

Two short years after that, her cabin was found broken into, with her dead inside. She had been murdered professionally with a quick and quiet blow to the back of the head followed by a machete hack to the front of her skull.

There are a number of suspects, although the murderer was never found. The machete still lay on the floor next to the bed, but the number of hands it passed through before being checked for prints rendered it inadequate evidence.

The blame was placed on her American colleague, Wayne McGuire, who found her. He was sentenced to death.

Luckily for him, he had fled the country before this sentence and maintains his innocence. Many say it is unlikely that he would have been the murderer given the good rapport he shared with Fossey.

She was, by many accounts, a difficult woman to encounter, but she was a fierce protector of the gorillas. She was a gutsy woman who went out on her own, won the apes’ affection, and dedicated the rest of her life to better understanding them as well as educating the public on what gorillas are really like.

She led the breakthrough study that proved to the world that gorillas are not scary beasts, but misunderstood creatures who are just as interested in us as we are in them.

After her death, she was buried not far from her cabin, surrounded by the graves of her beloved primates in what one could consider a family plot of sorts.