Humans have long dreamed of traveling to other planets, and the Space Race between the United States and Soviet Union stretching from the 1950s to the early 1970s was when this dream shifted to reality.

Soviet-born Yuri Gagarin wrote history by becoming the first human to enter space and safely return to Earth, setting an enormous milestone.

But there are some who harbor doubts about the details of the Soviet space program. Among the disturbing questions: Was Gagarin indeed the first person in space? What if he were merely the first to survive the journey and return? Were there other missions that failed and were hushed up?

Some sources suggest that Soviet casualties existed both before and after Gagarin’s historic flight on April 12, 1961, but they’ve been kept secret.

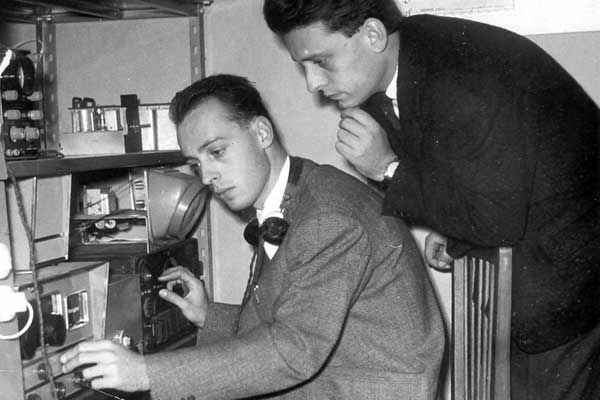

Two brothers from Italy, Achille and Giovanni Judica-Cordiglia, have presented their evidence to the public. They say they’ve obtained recordings from independent radio operators.

One of the tapes allegedly captured the suffering of an unknown astronaut as her life was extinguished by suffocation in a falling craft. Were the Soviets trying to set another milestone–to send the first woman into space?

Before trying to determine the truth, here is a little more context to the Soviet space program.

The days of the Space Race were not the most peaceful for the rest of the world, to say the least. It was perhaps the time in human history when science and politics intermingled to a boiling point.

In the early years of this era, when threats of global nuclear attack seemed about to become reality, it looked as if the Soviets were winning the race.

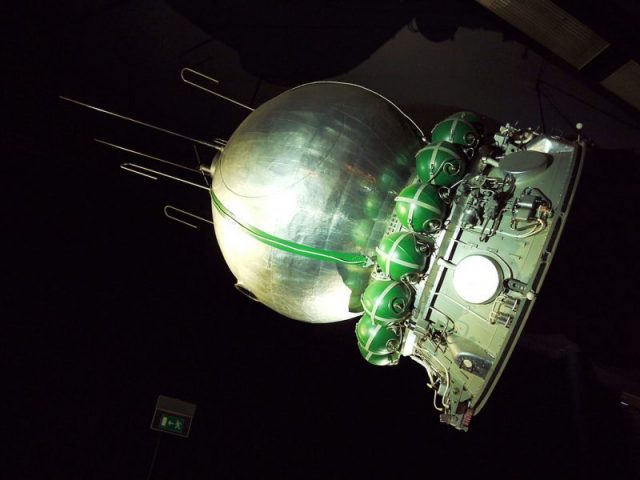

Not only was Russian cosmonaut Gagarin recognized as the first human in space, four years before that, the Soviets had successfully launched their first satellite in orbit. And four years after Gagarin, on March 18, 1965, cosmonaut Alexei Leonov won the honor of being the first human to walk in space.

Reaching such milestones were plus points on the Soviet side, and it meant the U.S. was falling behind.

But behind the ostensible success of the Soviet Union, not everything was shimmering and happy with this program. People elsewhere had many reasons to suspect darker goings on behind the facade.

It is a fact that dozens of lives were lost on the launchpads and in factories. One terrible incident took place in 1960 when the engines of a missile scheduled for a test flight burst, claiming the lives of about 80 people.

Despite the gravity of the Nedelin disaster and high death toll, Soviet officials largely tried to suppress news of the incident. Only in 1989 did authorities officially recognize some aspects of this unfortunate incident.

There was more than one isolated case. Numerous other casualties took place, as the Soviets struggled to cover up the mishaps.

Legends of Lost Cosmonauts

Gagarin died as he was piloting an aircraft in 1967. His death meant one more name, in this case a symbol of the Soviet Union space program, was added to the list of casualties.

Beyond this, some say that the death tolls were even higher than now acknowledged, that a substantial number of Soviet cosmonauts lost their lives due to malfunctioning space capsules and human error.

The Judica-Cordiglia brothers asserted they have been monitoring Soviet radio transmissions since 1957.

They were among those who suggested that Gagarin wasn’t the first human sent in space. To substantiate it, they picked nine recordings which contained Mayday calls from Soviet cosmonauts.

On one tape which is widely shared on the Internet, the voice of a woman can be heard who is muttering in Russian. From what can be understood from the transmission, the woman is obviously in distress.

“Talk to me! Talk to me! I am hot… I am hot!” she exclaims in part of the alleged transcription. “I am hot… isn’t this dangerous?”

If the recorded material is authentic, it means the first woman who reached space was Soviet-born and she tragically lost her life in a craft that apparently exploded.

According to this story, the woman faced issues as her craft tried to re-enter the atmosphere. By that point, the unknown woman had spent an entire week in space, and her oxygen resources were running low.

However, the Judica-Cordiglia evidence has been widely dismissed as a falsification.

When Soviet documents on such activities were declassified years after the Space Race was over, no reference was found to the missing cosmonauts. Various other sources and investigators have doubted that there were secret deaths.

Perhaps, they say, it was all part of propaganda, a continuation of the Cold War spirit.

As the Space Race unfolded, the Soviets experienced their own setbacks after the successes of the 1950s and early 1960s. This was largely due to budget cuts and channeling more money to things that took higher priority in Soviet society, such as insufficient housing and food shortages.

These were severe problems that needed fast response, and the space program suffered.

Few would associate the Soviet space program with failure. If the program had never taken place, the world, NASA included, would have been much poorer.

Think of the International Space Station, which applied the tremendous experience gained by Russians after years of initiating and running space stations.