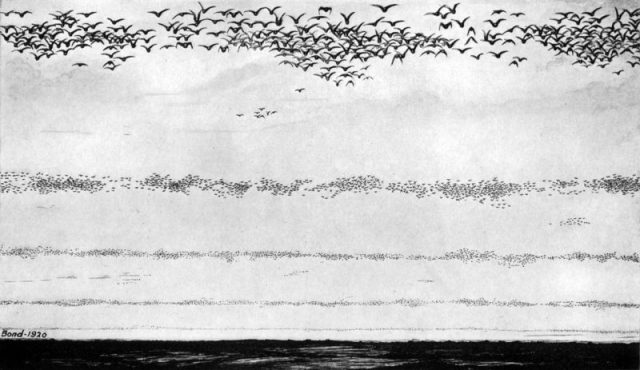

There was a time in the not-so-distant past when the daytime skies over North America would grow dark and noisy, and beneath the rumbling whir, the ground would turn white. People would tremble and drop in prayer. Horses would bolt in fear.

The daytime darkness could last for hours, and it could only mean one thing–a flyover by a seemingly endless flock of passenger pigeons. And when they were gone, the world was awash with pigeon poop.

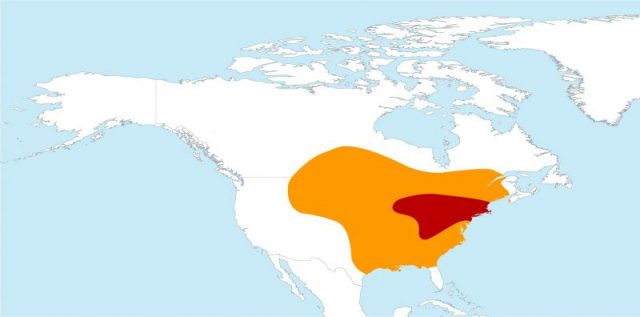

There was a time when these were the most abundant bird species in North America, and possibly the world. That time has passed. They are all gone now, just a few dusty, stuffed examples kept as curiosities on museum shelves and a few others stored in drawers.

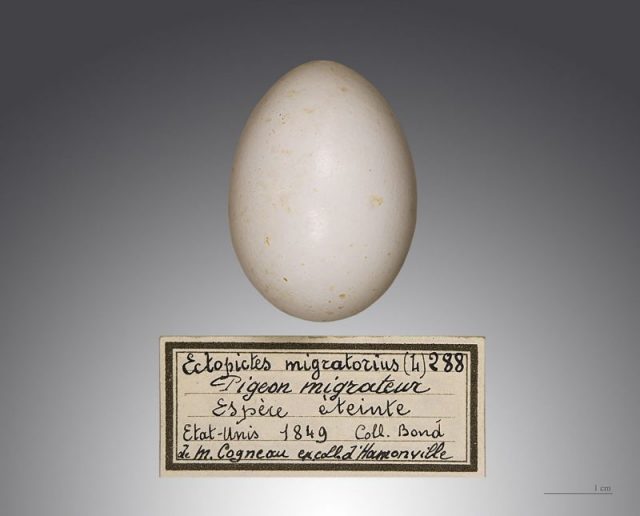

This great example of evolutionary success, the ruler of the skies, was brought down by man, aided by the emerging technology of the time. More on that in a bit. The lonely last survivor, a female of muted earth tones named Martha, lived to be nearly 30 years old at the Cincinnati Zoo. She died there in captivity in 1914, shaking with palsy and having never laid a fertile egg.

How did it come to this?

The very success of these birds was, in large part, the reason for the demise. Although they looked a lot like mourning doves, the males were big, up to 16 inches or so tall. The females were slightly smaller.

They were voracious birds, and their immense and clamorous flocks would head off for woodlands in search of acorns and beechnuts, their food of choice.

That was one of their problems. They could clean out a forest of these nuts, which also happened to be the main food source for free-ranging hogs that were allowed to fatten themselves up in the forest before early farmers would round them up for slaughter.

So, indirectly the birds were competing with farmers for their own key food source, the very bacon that farmers cured with smoke and salt and then relied on to get their families through the winter.

The size of the flock was one of the pigeon’s evolutionary advantages–there’s strength (and noise) in numbers–but for early pioneers, it came to mean something else.

These birds were large and tasty and when they were around, easy to bring down. A flock was a new and easy to obtain food source. Initially, the flocks were met with fear. Take an 1871 encounter in Fond du Lac, Wisconsin. Hunters there who flushed a large group of the birds were so overwhelmed by the noise and numbers that they dropped their guns.

The Commonwealth newspaper gave an impressive description of that event: “Imagine a thousand threshing machines running under full headway, accompanied by as many steamboats groaning off steam, with an equal quota of R.R. trains passing through covered bridges – imagine these massed into a single flock, and you possibly have a faint conception of the terrific roar,” it said.

But with so large of a flock, any shot into the air was virtually guaranteed to bring down a large, tasty bird or two. And many, just by their sheer numbers, were forced to fly low and could be batted out of the air with clubs. How did technology play into their demise? The newly emerged telegraph system now created a way for hunters to track the movement of a flock and follow them.

The railroads gave them a relatively speedy way to keep up. Scientists say the species might have been able to survive the wholesale slaughter, but their breeding sites were also targeted.

Nesting birds were disrupted, nests were torn down, and newly hatched squabs were taken to eat as a delicacy. This continued without any effort to save them and then, suddenly, they were gone. Silent. The loss was felt, however. Congressman John Lacey of Iowa, in 1900, introduced a law that would ban the shipping of unlawfully acquired game.

“The wild pigeons, formerly in flocks of millions, has entirely disappeared from the face of the earth,” he said when introducing the bill from the House floor. “We have given an awful exhibition of slaughter and destruction, which may serve as a warning to all mankind.”

The passenger pigeons’ demise also played into the later creation of the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1913, an effort to prevent the extinction of future bird species at the hands of man. Fast forward to new technology. Today there are ongoing efforts to revive the birds–in an altered fashion.

Related Article: 46,000-yr-old “Icebird” Found Totally Intact with Feathers and Beak

A group of genetic engineers is planning to change the genetic coding of the band-tailed pigeon, a close cousin of the extinct bird, so that it fits the coding of the passenger pigeon. Their goal is to raise the altered birds in captivity for a period and then release them into the wild in the 2030s.

Terri Likens‘ byline has appeared in newspapers around the world through The Associated Press. She has also done work for ABCNews, the BBC, and magazines that include High Country News, American Profile, and Plateau Journal. She lives just east of Nashville, Tenn.