A good spy needs many things: wits, courage, intelligence, and strength of heart.

Many would believe that two functioning legs would also be necessary when it came to spying, especially during World War Two, when communication was extremely limited and mobility was of the utmost importance.

Yet Virginia Hall, a woman with a wooden leg, was one of the most elusive and successful spies of World War Two.

Few would predict that Virginia Hall would end up on the Gestapo’s Most Wanted list, especially when one considered her upbringing.

Growing up in a wealthy American home, she attended prestigious colleges, studying multiple languages in the hopes of becoming a diplomat.

With wealth, class, and a family that stood behind her, she could have become just about anyone she wanted to be. She dreamed of joining the United States Foreign Service as a commissioned officer, but struggled to get accepted due to the difficulty of the entrance exam.

In 1931, she began to work for the Foreign Service as a consular clerk, hoping to gain experience that would assist her in taking a future exam. She had already failed twice before and realized that working abroad might be the only way for her to learn what was necessary.

So, she worked first in Warsaw and then Turkey. It would be her time in Turkey that would lead to her famous moniker “the Limping Lady.”

While hunting in 1933, Virginia was climbing over a fence when her shotgun accidentally discharged, seriously wounding her left foot. Despite the fact that she was taken to a medical facility, there was simply no way to save the foot due to gangrene.

A doctor was forced to amputate her limb below the knee, leaving Virginia with a wooden leg and a big problem: the Foreign Service wouldn’t accept amputees.

Virginia applied anyway, in the hopes of achieving her dream of becoming a foreign dignitary. Her dreams were shattered when she received a response that explained that since she was an amputee, she was not able-bodied and thus could not qualify for service.

After several failed attempts at appeals to this rejection, the terrible truth sank in. She would never be an officer for the Foreign Service.

This news would break her heart and lead her to resign from her job in the consulate. She departed from the Foreign Service in the hopes that France would have something of interest for her.

Virginia Hall arrived in France at worst possible time. Germany had begun its blitzkrieg against Poland in 1939 and the German war machine would focus its efforts on France on May 10, 1940. During this time, Virginia volunteered as an ambulance driver.

She worked diligently, but no amount of ambulances could protect France from being taken over by Nazi Germany.

With a newly occupied France, Virginia took off to Britain, hoping to find a more direct role in fighting against the German occupiers.

She made her way to the United States Embassy, where a welcome wagon was waiting for her, wanting to know every detail about what she had seen in France.

After she disclosed the information, she was offered a position to work as a code clerk. This was another desk job, not entirely different from the one she had been working at the Foreign Service. It would not satisfy her desire for adventure, not in the least.

Instead, Virginia found a better job, one with the British Special Operations Executive, an espionage organization. Their goal was to infiltrate, sabotage and conduct recon on the Nazi-occupied territories in Europe.

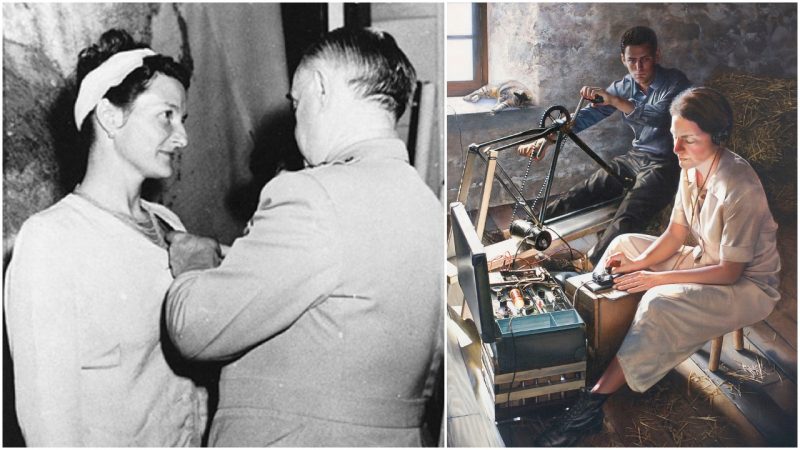

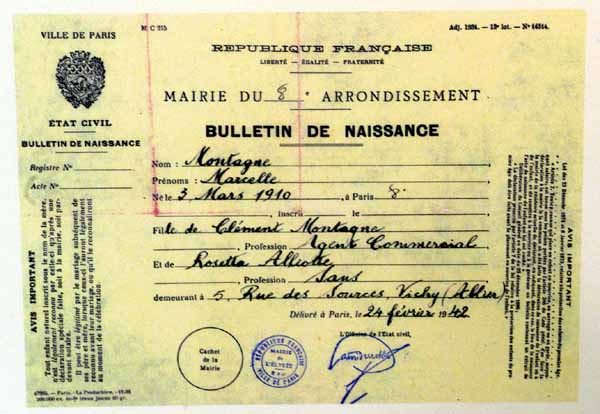

Virginia found the position of a spy to be far more engaging than becoming just another desk jockey. She went through intense training and was deployed to France in 1941, code-named Germaine.

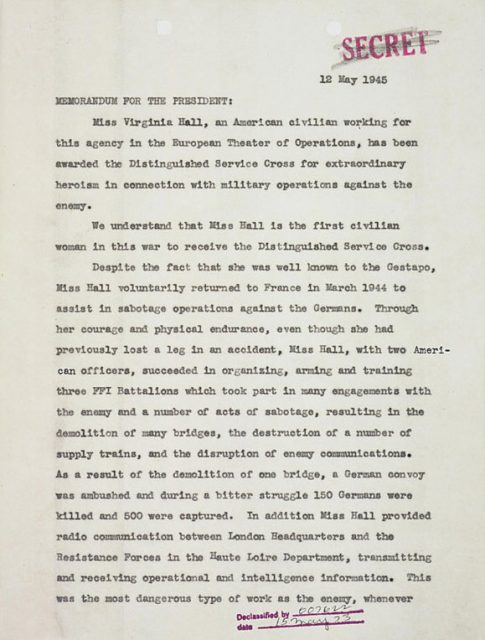

Her time in France would be extremely fruitful. While most agents would work for three months or so, Virginia dedicated a staggering 15 months to organizing raids, collecting intel, planning sabotage attacks, and freeing Allied POWs. She was exceptionally efficient at her job and would provoke the ire of the Gestapo.

Top 10 Surviving Buildings Built By The Nazis During Their Time In Power

Virginia was under no delusions, she knew that if she were captured she would be brutally tortured and then summarily executive for her actions. That knowledge did not stop her.

The Gestapo began to search for her frantically, with wanted posters spread out throughout France in the hopes of someone capturing her. With the heat so high, she departed from France and made her way to Spain for a brief time, making the grueling 50-mile trip over the Pyrenees Mountains alone.

While in a safehouse, she sent a message to her handlers in London, alerting them of the trip that she faced to reach them. She mentioned that she hoped that Cuthbert wouldn’t give her much trouble, a name she had given to her wooden leg. The SOE office, not knowing who Cuthbert was, recommending eliminating him if he was becoming a liability.

Upon her return, the British hailed her as a hero but refused to let her go back out to her post in France, as the heat was far too high. The Germans were still looking for the Limping Lady, and there was too much risk in her going back.

She responded to this by quitting the Special Operations Executive and joining the newly formed Office of Strategic Services, the predecessor of the CIA.

Returning to France with the aid of the OSS, Virginia’s orders were to aid the organization of the French Resistance. Thanks to her time in the country beforehand, she had plenty of contacts and information that would aid the resistance force that fought hard to liberate the country from Nazi oppression.

She would continue her espionage work until the end of the war in 1945, not once being captured by the Gestapo who so reviled her.

After the war, she sought after her original dream, to work for the Foreign Service, but that still wasn’t an option due to the department’s budgetary issues. Instead, she would end up working for the Central Intelligence Agency until the age of 60, where she was forced to retire by the rules.

In the end, Virginia Hall could have chosen to be anyone. She could have been a scholar or a socialite, but those things weren’t nearly as interesting to her as being one of the greatest spies of World War Two.

Andrew Pourciaux is a novelist hailing from sunny Sarasota, Florida, where he spends the majority of his time writing and podcasting.