Discussion of the second-season finale of HBO’s “dark odyssey” Westworld blew up the Internet in June, with fans of the addictive futuristic Western debating the meaning of the series’ last episode, their assessments ranging from “cryptic” to “baffling” to “Reddit-fueled storytelling.”

Perhaps the one thing these devotees could agree on is that there is something worth arguing over in Westworld. Its concepts of life and death, of fate and destiny, of control and consciousness, are meaty ones.

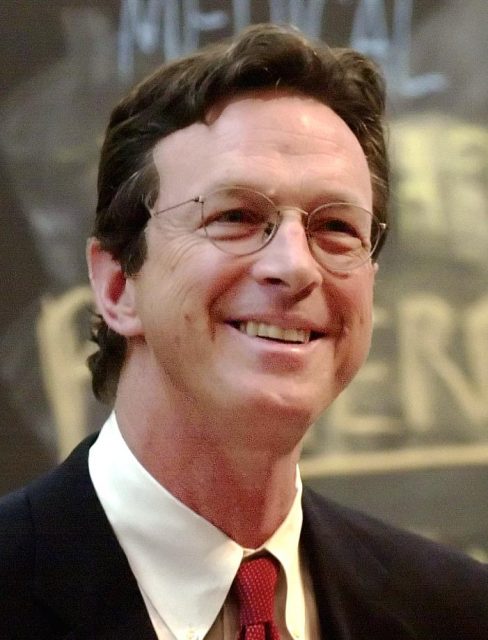

Such concepts were set forth in the original incarnation of this story, a 1973 film directed by a 31-year-old novelist and screenwriter named Michael Crichton. The current HBO series, starring Ed Harris, Anthony Hopkins, Evan Rachel Wood, and Thandie Newton, is a remake of that hit movie.

Westworld turned out to be a major influence on subsequent films, ranging from Terminator to Matrix, as well as serving as the introduction to pop culture of the idea of a “computer virus.”

Crichton’s film was set in what was then a near future of 1983 and starred Richard Benjamin as a businessman trying out an expensive new vacation recommended by his friend, James Brolin. The two men are conveyed to the resort Delos, where guests can explore their fantasies in either Western World, Medieval World, or Roman World.

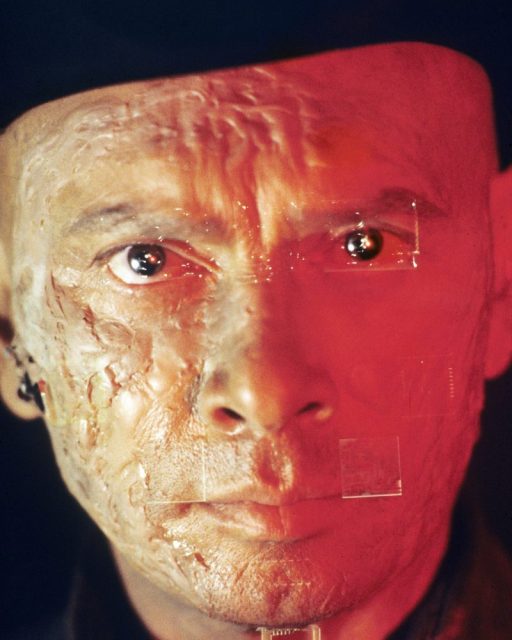

Occupying the parks are “machines” that look and talk and behave remarkably like humans, the most menacing of them all being The Gunslinger, played by Yul Brynner.

“There’s no way to get hurt in here,” Brolin reassures a nervous Benjamin shortly after they arrive. Dressed like cowboys, they drink whiskey, get into bar fights, break out of jail, and visit with gorgeous prostitutes in an Old West bordello.

On Benjamin’s first day of vacation, an intimidating man dressed in dark clothes bumps into him at a bar and then mocks him, saying “Get this boy a bib.”

Prodded by Brolin, Richard Benjamin challenges the man, played by Yul Brynner, to a gunfight–and the vacationing cowboy shoots his machine opponent “dead.”

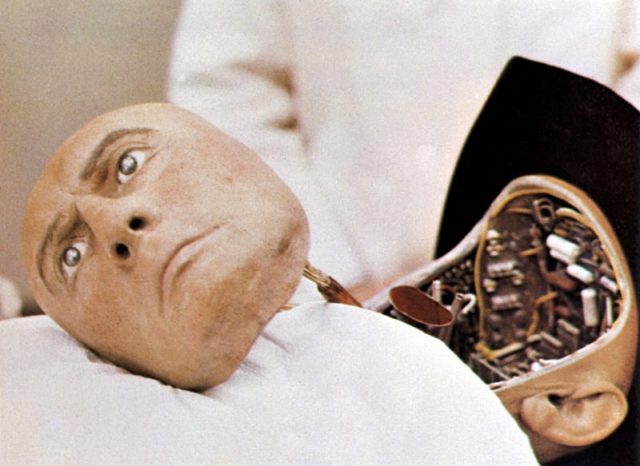

But as the film progresses, the various safety measures controlling the creations in the park–humans, animals, and reptiles–begin to disintegrate for reasons unknown (leading to the scientists’ description of a computer virus), and the guests’ vacations turn into violent nightmares.

Anyone who has seen the original film remembers Brynner relentlessly tracking and shooting at Benjamin, determined to kill him as he already has James Brolin.

Many of Crichton’s novels–400 million copies of the books sold worldwide–were made into films in the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s. It’s hard to conceive of the originality of Crichton’s work today, when most features films are reboots or based on comic books and old television series.

A Harvard graduate, Crichton earned a M.D. and worked as a doctor before deciding to devote himself to writing. His first big success was The Andromeda Strain in 1969, about a team of scientists frantically trying to contain a lethal virus released in a small town by a space object that crashes on Earth.

Crichton said he was inspired to write Westworld by various thing he observed. “I’d visited Kennedy Space Center and seen how astronauts were being trained–and I realized that they were really being trained to be machines. They were working very hard to makes their responses and their heartbeats as predictable as possible.”

Things you may not know about Steve McQueen

The other influence on the writer was going to Disneyland and seeing “Abraham Lincoln” stand up every 15 minutes to give the Gettysburg Address. In this case, a machine was made to look and talk like a recognizable human being.

For the first time, Crichton decided to jump right to film rather than write this idea as a novel.

“It didn’t work as a novel, and I think the reason for that is the rather special structure of this particular story,” Crichton said later. “It’s about an amusement park built to represent three different sorts of worlds: a Western world, a Medieval world, and a Roman world. The actual dealing of those three worlds–and also the kinds of fantasies that people experienced in them–were movie fantasies, and they got to be strange-looking on the written page. In some ways, it’s a lot cleaner as a movie, because it’s a movie about people acting out movie fantasies.”

MGM agreed to let Crichton direct a film from his own screenplay if he could make it for no more than $1.3 million and he wouldn’t take more than 30 days. He accepted these challenges.

Within such tight restrictions, Crichton managed to create a landmark innovation: He was the first director to use computer-generated imagery as a movie special effect while showing the point of view of Brynner’s Gunslinger.

While Richard Benjamin is a relatable leading man in the film, it is Yul Brynner, the “monotone maniac” as one fan describes him, who steals it. Years before, he played a “good” gunslinger as Chris, the black-clad leader in The Magnificent Seven. In Westworld, he turned that character inside out.

GQ magazine said, “As played by Yul Brynner–riffing so heavily on his character from The Magnificent Seven that he even wears the exact same costume–the Gunslinger is the Terminator before the Terminator was the Terminator: emotionless, implacable, and virtually unstoppable.”

Unstoppable machines have been a pop culture go-to since the 1960s. Aside from Terminator, the idea of robots running amok is explored in Blade Runner, based on a 1968 novel by Philip K. Dick. It’s a concept that the various Star Trek incarnations also make heavy use of, and perhaps in a bow to Star Trek, Crichton cast Gene Roddenberry’s wife, Majel Barrett, as a Western saloon madame in his film.

The showrunners of HBO’s remake of Westworld are unabashed admirers of what Michael Crichton, who died in 2008, achieved with this film.

After Westworld, a commercial success in 1973, he wrote novels that included Sphere, Jurassic Park, Rising Sun, Disclosure, Congo, Eaters of the Dead (The 13th Warrior), and Timeline.

“What you feel in Westworld is there’s this larger world that he barely has time to explore, and it leaves you breathless,” says Jonathan Nolan. “It’s a film that anticipated so many advances in technology. He was a visionary. Some of the questions Crichton had in his film we’re hoping to elaborate on in the series. As exotic as they seemed years ago, they are now becoming frighteningly relevant.”

Nancy Bilyeau, a former staff editor at Entertainment Weekly, Rolling Stone, and InStyle, has written a trilogy of historical thrillers for Touchstone Books. For more information, go to www.nancybilyeau.com.