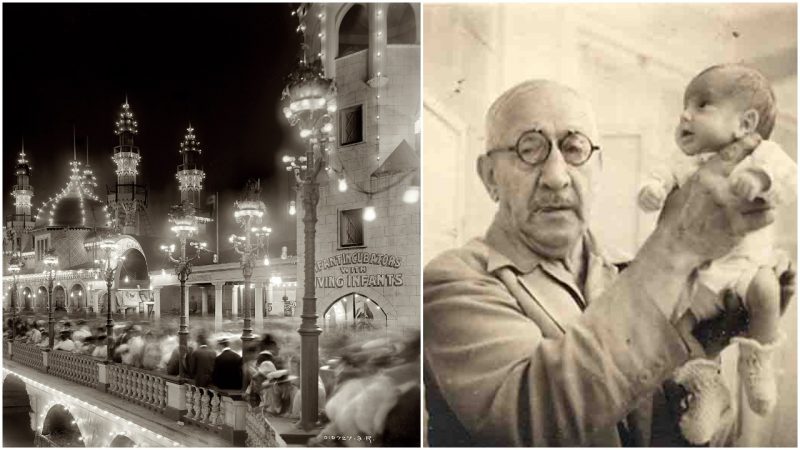

In 1903, a very strange sideshow opened for business on Coney Island. Home to strippers, sword swallowers, shooting galleries, animal pageantry, freak shows, and thrill-rides that threw young lovers screaming into each others’ arms, Coney Island was the summer playground for New Yorkers—affectionately known as Sodom by the Sea.

But one popular sideshow was bizarre even for Coney Island: It featured live premature infants in incubators, and the public paid to watch them “bake.” Outside, a carnival barker hollered, “Come this way, ladies and gentlemen. Maybe the future president is inside!”

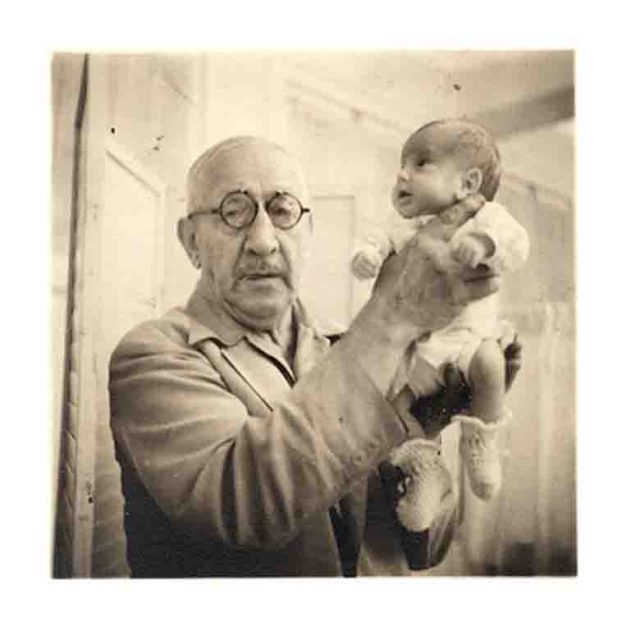

The show’s proprietor went by the name of Dr. Martin Arthur Couney, and for the next 40 years, while other attractions came and went, he would continue to show tiny preemies on Coney Island and at the Atlantic City Boardwalk (home to the Miss America Pageant and the Heinz Pickle Pier).

He also held shows on the midway of major world’s fairs, including those held in Chicago, New York, San Francisco, Buffalo, and Omaha. Plus, he had satellite outposts in amusement parks in Minneapolis, Denver, Chicago, and other cities.

As time went on and his fame grew, the mysterious Martin Couney continued to burnish his credentials. He claimed he was born in Alsace, earned medical degrees in Liepzig and Berlin, and served as the hand-chosen protégé of a world renowned (and conveniently dead) French pediatrician named Pierre Constant Budin. It was Dr. Budin, he said, who first sent him to exhibit premature babies, at the Berlin Industrial Exposition of 1896.

This incubator show was dubbed Kinderbrutanstalt (literally, child hatchery)—and before it even opened, it had inspired German drinking hall songs. The show’s purpose was to demonstrate the newly invented infant incubator, and it was a sensational success. But exactly why Martin Couney then left Europe for America’s boardwalks was something he never made clear.

In truth, Dr. Martin Couney fabricated almost everything about himself, including all three parts of his name—prefix, first, and surname. He was born Michael Cohn in Krotoschin, Prussia (now Poland), and quietly arrived in New York at the age of 18.

As it happens, there really was a “child hatchery” at the Berlin Industrial Exposition—but the future Dr. Martin Couney had nothing to do with it. (Nor, for that matter, did Dr. Pierre Budin; the show was the work of a French engineer named Alexandre Lion.)

But in America, Martin Couney stayed in business because was decades ahead of the medical establishment.

Traveling Coney Island exhibit

Despite his lack of medical training, he knew how to keep tiny preemies alive. He used the same type of incubators that Alexandre Lion had shown in Berlin and that American hospitals had largely rejected. He hired “assistants” who were licensed to practice medicine, relied on highly skilled nurses (including his wife), and kept the premises immaculate—a claim that could not be made for hospitals at the time.

As a result, in the wee years of the 20th Century, his show was saving infants weighing two and three pounds—patients for whom doctors saw no chance. He treated babies of all races, from all backgrounds, and never charged his patients’ parents a dime, funding their care by charging audience admission. While this was a blessing for poor parents, rich parents sent their babies too—because no better care could be bought.

With overall infant mortality high, tiny preemies—called “weaklings” in the medical literature—were simply not a priority. As the 19-aughts rolled into the teens and twenties, a growing eugenics movement created an environment hostile toward anyone potentially “unfit.”

New York and Atlantic City-area doctors who had their patients’ best interest in mind strongly urged parents to send their newborns to the boardwalk as their best and often only hope.

Martin Couney liked to say he was “making propaganda for preemies,” showing the public these children could be saved, endlessly wining and dining physicians in the hopes of persuading them.

He was extravagant and charismatic, a glad-hander and gourmet, ready to pick up any check. But his ideas might not have caught on were it not for his friendship with a Chicago physician named Julius Hess.

The impeccable Dr. Hess was everything Martin Couney was not, with stellar degrees, a formal, commanding presence, serious institutional affiliations, and the means to publish clinical results in medical journals. Early in his career, Dr. Hess had been inspired by the showman to fight for the care of preemies, and he too devoted his life to this pursuit.

In 1933 and ‘34, the two friends joined forces at the Chicago World’s Fair in order to show the nation that preemies could—and should–be saved. With the city’s health commissioner and the editor of the Journal of the American Medical Association on their side, they broadcast coast to coast. The following year, Chicago became the first American city with comprehensive care for preemies as public health policy; eventually, Chicago became a model for the rest of the country.

Martin Couney’s story has both a sad and happy ending. During his lifetime, the showman had grown enormously rich; he lived in a beautiful home by the sea, traveled the world, and dined in all the best places. The New York World’s Fair of 1939-40 was to be his last hurrah. At this point, he was 70 years old and widowed, and he planned to end his career with a bang.

Unfortunately, the bang was a bust. Almost all the concessionaires lost money, and Couney, who’d funded his exhibit personally, with no investors, went flat broke. He died in 1950, penniless and largely forgotten.

The enduring happy ending is that over the course of his career, Martin Couney saved the lives of 6,500 to 7,000 children. Some of them are still alive.

He is the rightful father of American neonatology—a shyster and a savior; a bold, outrageous outsider who loved life and who did what physicians could not.

Dawn Raffel is the author of ‘The Strange Case of Dr. Couney,” to be published by Blue Rider Press on July 31, 2018. For more information, go to www.dawnraffel.com